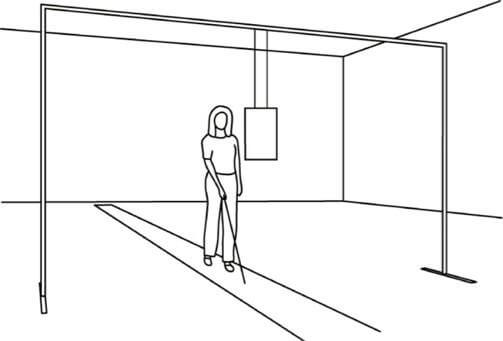

People who are visually impaired will often use a cane to feel out their surroundings. With training and practice, people can learn to use the pitch, loudness and timbre of echoes from the cane or other sounds to navigate safely through the environment using echolocation.

Bo Schenkman, an associate professor at KTH Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm, Sweden, will present a summary of some aspects of his work on human echolocation during Acoustics ’17 Boston, the third joint meeting of the Acoustical Society of America and the European Acoustics Association being held June 25-29, in Boston, Massachusetts.

A better understanding of echolocation may improve methods for teaching the technique to people who have lost their sight later in life, and yield additional insights into human hearing. “Eventually I hope the research can give a result that can aid blind and visually impaired people,” Schenkman said.

Many individuals who were born blind or who lost their sight early in life are highly skilled at using echoes that bounce off objects, walls, hallways and buildings to find their way around. The majority of people use the tapping of their canes to echolocate — the action calls less attention to themselves. But others add their own sounds like clicking, shushing or snapping noises to detect objects around them.

In past research, Schenkman mostly used sound recordings to probe the ability of sighted and blind individuals to detect the source of echoes. By reanalyzing previously collected data using auditory models, he identified some of the specific informational cues that visually impaired people use to echolocate. The analysis shows that people use not only the pitch and loudness of echoes, which is well established, but that they may also use the timbre, especially the sharpness aspects of timbre.

His work shows that, on average, visually impaired people are better than sighted individuals at perceiving the sound quality of two sounds that are close together in time. Blind people can also more easily counteract the “precedence effect,” a phenomenon that occurs when sounds overlap, and a person judges the location of the sounds to be from the location of the first arriving sound, rather than from the ones that arrive later.

Human echolocation shares some similarities with animal echolocation, though people use the skill to compensate for their sight, rather than as an additional sense. For both humans and bats, there is an ideal interval to emit sounds to most effectively echolocate. Humans, however, listen for the sound as well as its echo, while most bats seem to rely on just the echo.

“It’s a byproduct of our hearing system that we can use echolocation, so we’re not as proficient at it as bats,” Schenkman said. However, “I think one can learn much from differences between humans and bats, to compare how the systems work.”

Research into echolocation can inform Orientation and Mobility training, which helps people who are blind or visually impaired to navigate their environment. People who become blind early in life often learn to use their hearing, including echolocation, more efficiently. But for individuals who became impaired later in life, echolocation training can help them to move through the world with greater independence and safety.