Group A Streptococcus bacteria cause a variety of illnesses that range from mild nuisances like strep throat to life-threatening conditions including pneumonia, toxic shock syndrome and the flesh-eating disease formally known as necrotizing fasciitis. The life-threatening infections occur when the bacteria spread underneath the surface of the skin or throat and invade the underlying soft tissue. A 2005 study published in The Lancet attributed half a million deaths worldwide each year to group A Streptococcus.

“In 24 to 48 hours, you can go from being healthy to having a limb amputated to save your life,” said Kevin McIver, professor of cell biology and molecular genetics at the University of Maryland, College Park. “And we don’t really know why or how the bacteria do that.”

In a new study, McIver’s laboratory and researchers at the University of Maryland School of Medicine identified two genes important for invasive group A Streptococcus infections in mice. The genes, subcutaneous fitness genes A (scfA) and B (scfB), may prove to be promising clinical targets in the fight against these infections, as there are no vaccines against group A Streptococcus or effective treatments for invasive infections. The study was published online on August 23, 2017, in the journal PLOS Pathogens.

Led by Yoann Le Breton, the study’s first author and a research assistant professor in McIver’s group, the researchers discovered scfA and scfB by performing transposon sequencing on the entire group A Streptococcus genome. Transposons, also known as jumping genes, are short sequences of DNA that physically move within a genome, mutating genes by jumping into them. If the mutation causes an interesting effect, scientists can identify the mutated gene by locating the transposon, sequencing the DNA surrounding the transposon and mapping its location in the genome.

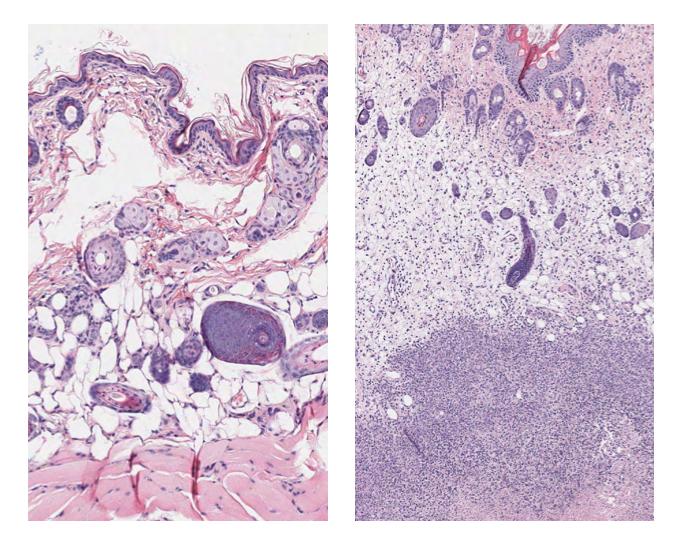

“Invasion under the skin, or subcutaneously, is not the norm for group A Streptococcus bacteria; it’s actually very rare,” McIver explained. “We hypothesized that there must be genes in the bacteria important for invading soft tissues and surviving under the skin. And we tested that theory by using transposons to make thousands of different individual mutants that we used to infect a subcutaneous environment in mice.”

McIver and his colleagues used a transposon called Krmit–which they created in a previous study–to generate a collection of approximately 85,000 unique mutants in a group A Streptococcus strain. They injected the mutant strains into mice, which resulted in humanlike infections. The transposon was named for the Muppets character Kermit the frog, whose creator Jim Henson, a 1960 College Park alumnus, died of toxic shock syndrome following group A Streptococcal pneumonia.

“We were particularly interested in the mutations that didn’t come out the other end–the ones not found in the surviving bacteria from the infected tissue,” McIver said. “These genes would be good targets for a vaccine or treatment because the bacteria missing these genes did not flourish in the infection site.”

The researchers identified 273 scf genes as potentially involved in establishing infection under the skin, but two genes stood out: scfA and scfB. Based on patterns in their DNA sequences, these genes likely encode proteins in the bacterial membrane. This is a prime location for gene products involved in infection because many dangerous bacteria secrete toxins or proteins through the membrane to attack the host. Additional experiments showed that bacteria lacking scfA or scfB had difficulty spreading from under the skin to the bloodstream and other organs.

The results suggest that these two genes are involved in the invasion process and may be potential targets for therapeutics.

“The next steps will be to expand the study to include multiple animal models, and these experiments are already underway,” said Mark Shirtliff, a co-author of the study and a professor in the Department of Microbiology and Immunology at the University of Maryland School of Medicine and the Department of Microbial Pathogenesis at the University of Maryland School of Dentistry. “We can also begin to formulate improved therapies and vaccines against group A streptococcus infections and their complications such as rheumatic heart disease, pneumonia and necrotizing fasciitis.”

McIver also looks forward to using transposon sequencing to study other ways bacteria attack humans.

“Transposon sequencing can be used to probe how bacteria infect humans in any environment you can think of,” McIver said. “Like group A Streptococcus, many pathogenic bacteria have completely sequenced genomes, but we don’t know what most of the genes are doing. We’re excited to have a method to interrogate all that unknown genetic material to better understand human infections.”