Scientists are a step closer to predicting when and where earthquakes will occur after taking a fresh look at the formation of the Andes, which began 45 million years ago.

Published today in Nature, research led by Dr Fabio Capitanio of Monash University’s School of Geosciences describes a new approach to plate tectonics. It is the first model to go beyond illustrating how plates move, and explain why.

Dr Capitanio said that although the theory had been applied only to one plate boundary so far, it had broader application.

Understanding the forces driving tectonic plates will allow researchers to predict shifts and their consequences, including the formation of mountain ranges, opening and closing of oceans, and earthquakes.

Dr Capitanio said existing theories of plate tectonics had failed to explain several features of the development of the world’s longest land-based mountain chain, motivating him to take a different approach.

“We knew that the Andes resulted from the subduction of one plate, under another; however, a lot was unexplained. For example, the subduction began 125 million years ago, but the mountains only began to form 45 million years ago. This lag was not understood,” Dr Capitanio said.

“The model we developed explains the timing of the Andes formation and unique features such as the curvature of the mountain chain.”

Dr Capitanio said the traditional approach to plate tectonics, to work back from data, resulted in models with strong descriptive, but no predictive power.

“Existing models allow you to describe the movement of the plates as it is happening, but you can’t say when they will stop, or whether they will speed up, and so on.

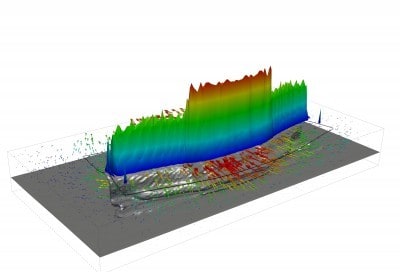

“I developed a three-dimensional, physical model – I used physics to predict the behaviour of tectonic plates. Then, I applied data tracing the Andes back 60 million years. It matched.”

Collaborators on the project were Dr Claudio Faccenna of Universita Roma Tre, Dr Sergio Zlotnik of UPC-Barcelona Tech, and Dr David R Stegman of University of California San Diego. The researchers will continue to develop the model by applying it to other subduction zones.