As people age, their intestinal stem cells begin to lose their ability to regenerate. These stem cells are the source for all new intestinal cells, so this decline can make it more difficult to recover from gastrointestinal infections or other conditions that affect the intestine.

This age-related loss of stem cell function can be reversed by a 24-hour fast, according to a new study from MIT biologists. The researchers found that fasting dramatically improves stem cells’ ability to regenerate, in both aged and young mice.

In fasting mice, cells begin breaking down fatty acids instead of glucose, a change that stimulates the stem cells to become more regenerative. The researchers found that they could also boost regeneration with a molecule that activates the same metabolic switch. Such an intervention could potentially help older people recovering from GI infections or cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy, the researchers say.

“Fasting has many effects in the intestine, which include boosting regeneration as well as potential uses in any type of ailment that impinges on the intestine, such as infections or cancers,” says Omer Yilmaz, an MIT assistant professor of biology, a member of the Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research, and one of the senior authors of the study. “Understanding how fasting improves overall health, including the role of adult stem cells in intestinal regeneration, in repair, and in aging, is a fundamental interest of my laboratory.”

David Sabatini, an MIT professor of biology and member of the Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research and the Koch Institute, is also a senior author of the paper, which appears in the May 3 issue of Cell Stem Cell.

“This study provided evidence that fasting induces a metabolic switch in the intestinal stem cells, from utilizing carbohydrates to burning fat,” Sabatini says. “Interestingly, switching these cells to fatty acid oxidation enhanced their function significantly. Pharmacological targeting of this pathway may provide a therapeutic opportunity to improve tissue homeostasis in age-associated pathologies.”

The paper’s lead authors are Whitehead Institute postdoc Maria Mihaylova and Koch Institute postdoc Chia-Wei Cheng.

Boosting regeneration

For many decades, scientists have known that low caloric intake is linked with enhanced longevity in humans and other organisms. Yilmaz and his colleagues were interested in exploring how fasting exerts its effects at the molecular level, specifically in the intestine.

Intestinal stem cells are responsible for maintaining the lining of the intestine, which typically renews itself every five days. When an injury or infection occurs, stem cells are key to repairing any damage. As people age, the regenerative abilities of these intestinal stem cells decline, so it takes longer for the intestine to recover.

“Intestinal stem cells are the workhorses of the intestine that give rise to more stem cells and to all of the various differentiated cell types of the intestine. Notably, during aging, intestinal stem function declines, which impairs the ability of the intestine to repair itself after damage,” Yilmaz says. “In this line of investigation, we focused on understanding how a 24-hour fast enhances the function of young and old intestinal stem cells.”

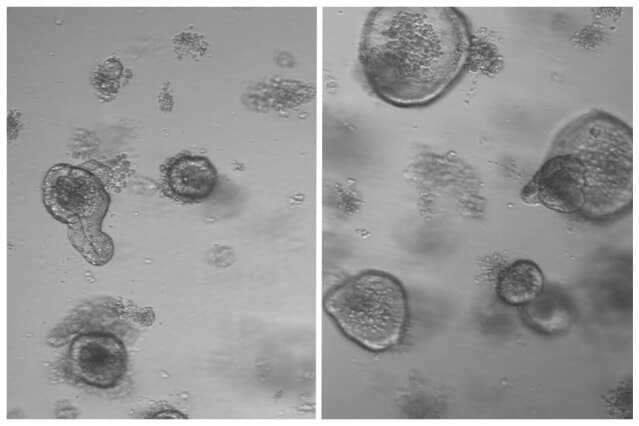

After mice fasted for 24 hours, the researchers removed intestinal stem cells and grew them in a culture dish, allowing them to determine whether the cells can give rise to “mini-intestines” known as organoids.

The researchers found that stem cells from the fasting mice doubled their regenerative capacity.

“It was very obvious that fasting had this really immense effect on the ability of intestinal crypts to form more organoids, which is stem-cell-driven,” Mihaylova says. “This was something that we saw in both the young mice and the aged mice, and we really wanted to understand the molecular mechanisms driving this.”

Metabolic switch

Further studies, including sequencing the messenger RNA of stem cells from the mice that fasted, revealed that fasting induces cells to switch from their usual metabolism, which burns carbohydrates such as sugars, to metabolizing fatty acids. This switch occurs through the activation of transcription factors called PPARs, which turn on many genes that are involved in metabolizing fatty acids.

The researchers found that if they turned off this pathway, fasting could no longer boost regeneration. They now plan to study how this metabolic switch provokes stem cells to enhance their regenerative abilities.

They also found that they could reproduce the beneficial effects of fasting by treating mice with a molecule that mimics the effects of PPARs. “That was also very surprising,” Cheng says. “Just activating one metabolic pathway is sufficient to reverse certain age phenotypes.”

Jared Rutter, a professor of biochemistry at the University of Utah School of Medicine, described the findings as “interesting and important.”

“This paper shows that fasting causes a metabolic change in the stem cells that reside in this organ and thereby changes their behavior to promote more cell division. In a beautiful set of experiments, the authors subvert the system by causing those metabolic changes without fasting and see similar effects,” says Rutter, who was not involved in the research. “This work fits into a rapidly growing field that is demonstrating that nutrition and metabolism has profound effects on the behavior of cells and this can predispose for human disease.”

The findings suggest that drug treatment could stimulate regeneration without requiring patients to fast, which is difficult for most people. One group that could benefit from such treatment is cancer patients who are receiving chemotherapy, which often harms intestinal cells. It could also benefit older people who experience intestinal infections or other gastrointestinal disorders that can damage the lining of the intestine.

The researchers plan to explore the potential effectiveness of such treatments, and they also hope to study whether fasting affects regenerative abilities in stem cells in other types of tissue.

The research was funded by the National Institutes of Health, the V Foundation, a Sidney Kimmel Scholar Award, a Pew-Stewart Trust Scholar Award, the MIT Stem Cell Initiative through Fondation MIT, the Koch Institute Frontier Research Program through the Kathy and Curt Marble Cancer Research Fund, the American Federation of Aging Research, the Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation, the Robert Black Charitable Foundation, a Koch Institute Ludwig Postdoctoral Fellowship, a Glenn/AFAR Breakthroughs in Gerontology Award, and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

There is good reason that this works in humans, too but it will probably require a much longer fast. A 24-hr fast for a mouse is a very long time because its metabolism is so much faster than ours. My guess based on Longo’s research is that this benefit will require 3 days, maybe 4 for humans. The first day, we’re still living on stored glycogen in the liver.