Patients with a rare skin disease, commonly called Butterfly Syndrome, that causes chronic blistering and extensive scarring also develop an aggressive and fatal form of cancer early in life. Now an international team of scientists led by researchers at the Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center – Jefferson Health finds that immune system-related enzymes are major contributors to the cancer’s development. The discovery identifies new therapeutic strategies and reveals how chronic inflammation can spur cancer.

“We’re describing for the first time a mechanism that instigates tissue damage-driven cancers,” said senior author Andrew South, PhD, an associate Professor in the department of Dermatology and Cutaneous Biology at Jefferson (Philadelphia University + Thomas Jefferson University) who published the work August 22nd in the journal Science Translational Medicine.

Dr. South studies a severe skin disorder called recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa (RDEB). The genetic disease makes the skin incredibly fragile–even the slightest touch can cause damage as the condition results from mutations in a gene that helps to hold layers of the skin together. A small scratch or brush of the skin can easily separate the layers and cause blisters that do not heal well. This often leads to considerable scarring. Most individuals with RDEB also develop a skin cancer called squamous cell carcinoma early in life.

“RDEB is a skin condition that leads to profound disability and lifelong pain for those who have it,” said Sharmila Collins, Founder and Trustee of Cure EB (formerly Sohana Research Fund) and mother of a child with RDEB. “The daily routine of pricking blisters and dressing wounds takes hours, is very painful and has a profound impact on family life. After years of daily management, sufferers are at high risk of developing a very aggressive squamous cell carcinoma that leads to early death. Research into the mechanisms of this particular cancer with the aim of treating it, is therefore a priority. We are thrilled to have been able to support researchers at the forefront of this work.”

Squamous cell carcinoma is a type of cancer that develops in tissues that act as a barrier to the environment such as the skin, but also the oral cavity, lungs and cervix. Many people develop this kind of cancer in their skin from sun exposure, and when detected early, squamous cell carcinoma of the skin is curable. But that’s not the case for RDEB patients. Their five-year survival rate is close to zero.

Dr. South and colleagues wanted to figure out why the cancer is so frequent in RDEB patients and what makes it so aggressive. He reached out to labs and clinics around the world that treat these patients to collect as many RDEB squamous cell carcinoma samples as possible, including Jefferson’s clinic for Adult EB patients, one of the few that offers treatment for cancer in this population. Then he and his team scrutinized the tumors’ genetic makeup.

When the researchers examined the genetic sequences of RDEB patients’ tumors, they found a group of enzymes called apolipoprotein B editing complex (APOBEC) caused a large proportion of the cancer’s mutations. These proteins help our immune systems by editing nucleic acid messages in pathogens, and in us. When APOBEC enzymes edit our DNA’s messages for example, they increase the diversity of antibodies available to fight off infection. In RDEB patients, inflammation from continued tissue damage and the persistent threat of microbial infection ratchets up APOBEC expression, leading the enzymes to attack the patient’s DNA, which then creates cancer-causing mutations.

In fact, DNA changes from APOBEC account for 42 percent of mutations in an RDEB skin tumors. In most people with skin cancer, APOBEC is much less active, making up about only about two percent of the mutations in tumors. The finding means these APOBEC alterations distinguish RDEB skin cancer from the kind caused by sunlight. And since RDEB skin tumors develop in places with chronic wounds, the discovery further provides a mechanism for how inflammation and tissue damage spur cancer progression.

“We show for the first time that a different mutational process appears to promote cancers caused by chronic tissue damage, as observed in RDEB. This is potentially an invisible force that also contributes to a much broader range of cancers,” said first author Raymond Cho, MD, PhD, a UCSF Health dermatologist and associate professor in the Department of Dermatology at UCSF.

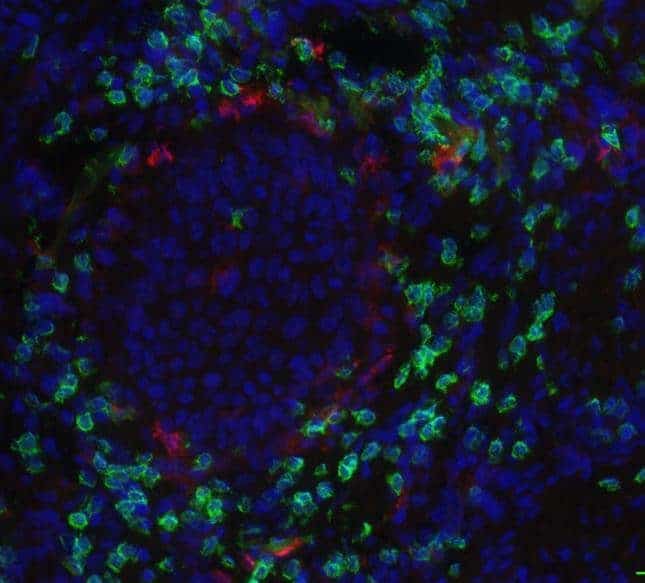

Dr. South and colleagues then looked at which genes turn off or on and by how much in RDEB skin tumors compared to squamous cell carcinomas in other tissues. When the researchers grouped genes that perform similar biological functions together, they discovered RDEB skin cancers share more in common with those that develop in the oral cavity than cancer that develops in the skin from UV exposure. The finding reveals RDEB skin cancer acts more like squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity than the skin. Together with previous research that shows that like RDEB skin cancer, squamous cell carcinoma in the oral cavity is more aggressive than in the skin and also has more APOBEC mutations, Dr. South’s discovery suggests therapeutic approaches for oral cancer might be effective against RDEB skin cancers.

“We should be treating those cancers in the RDEB patients similarly to how we treat cancer in the oral cavity,” said Dr. South. “That’s a direct clinical outcome from this research.” Immune checkpoint inhibitors such as nivolumab, which the FDA has approved to treat oral squamous cell carcinoma, might also work against RDEB skin cancer for example, but researchers would first need to prove its efficacy.

“RDEB is a devastating and life-threatening disease that has a major impact on patients’ quality of life and no approved treatment options. We are honored to work with Dr. Andrew South toward accelerating research on treatments and cures for EB and to deliver hope, healing, and results for families around the world,” said Michael Hund, Executive Director, EB Research Partnership.

As a result of the new work, the Department of Defense recently awarded Dr. South with a grant for nearly $1.75 million USD to figure out what turns APOBEC enzymes on and to look for compounds that disable them. “Such inhibitors could be used to help prevent mutation acquisition and skin cancer development in RDEB patients,” said Dr. South.