Nearly two decades after a class of once-promising cancer drugs called MMP inhibitors mysteriously failed in clinical trials, scientists think they may have an explanation for what went wrong.

The findings in C. elegans worms could lead to better ways to prevent the first steps of metastasis, the spread of the disease responsible for 90 percent of cancer deaths.

MMP inhibitors were aimed at blocking a group of enzymes long thought key to cancer’s spread. Called matrix metalloproteinases, the enzymes help dissolve the tough outer membrane that surrounds both tumors and healthy tissues, allowing cancer cells to escape from their original locations and set up shop in other organs.

Yet despite promising results in mice, MMP inhibitors didn’t help people with cancer live longer and some patients developed serious side effects.

The new findings, from a team led by biology professor David Sherwood at Duke University, suggest that invasive cells switch to brute force and build a battering ram when their dissolving enzymes aren’t available.

The study was published online January 24 in the journal Developmental Cell.

To metastasize, a tumor cell must first penetrate a dense sheet-like mesh of proteins and other molecules called the basement membrane, which surrounds tissues like a Kevlar wrapper.

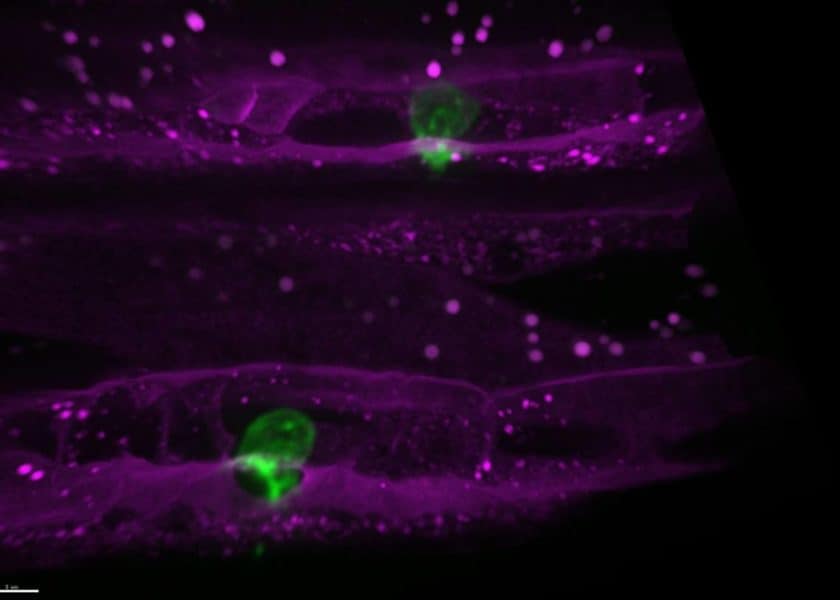

Sherwood and his team study a similar process in transparent 1-millimeter worms, which — unlike human tumors — allow researchers to watch invading cells in action.

Normal worm cells use their MMP enzymes to help cut through the matrix of proteins in the basement membrane like molecular scissors, the researchers say. But cells in “knockout” worms lacking the MMP enzymes instead build a large protrusion that pummels and smashes its way through with brute force, said Duke research scientist Laura Kelley, who led the experiments.

Normally the invading cell pushes through a narrow hole, “kind of like the escape tunnel in ‘The Shawshank Redemption,’” Sherwood said. “But in knockout worms it’s more like the Kool-Aid Man when he busts through walls.”

The researchers also found that the protrusion is filled with stiff networks of actin filaments for a harder-hitting punch. To fuel the blows, the cell also moves mitochondria — the power plants of the cell — to the site of the ram.

The team also developed a screening technique that enabled them to identify and target a mitochondrial gene that invasive cells rely on in the absence of MMPs, and were able to prevent the cells from breaking through.

The researchers hope their work in worms will identify drug targets that could one day be tested in combination with MMP inhibitors to better treat metastasis in humans.

If researchers can develop drugs that inhibit both MMP enzymes and the battering rams, they may be able to more effectively block cell invasion and keep cancer from spreading.

This research was funded by the American Cancer Society (129351-PF-16-024-01-CSM), the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society (3601-11/388-0036), the National Cancer Institute (4R00CA154870-03), the National Institutes of Health (F32GM103148, NIGMS R35, MIRA GM118049, R21HD084290), Foundation Association pour la Recherche sur le Cancer and the PSL Research University (ANR-10-IDEX-0001-02 PSL).

Other authors include Qiuyi Chi, Eric Hastie, Adam Schindler and Yue Jiang of Duke; Rodrigo Cáceres and Julie Plastino of the Curie Institute and Sorbonne University in Paris; and David Matus of Stony Brook University.

CITATION: “Adaptive F-actin Polymerization and Localized ATP Production Drive Basement Membrane Invasion in the Absence of MMPs,” Laura Kelley, Qiuyi Chi, Rodrigo Cáceres, Eric Hastie, Adam Schindler, Yue Jiang, David Matus, Julie Plastino and David Sherwood. Developmental Cell, January 24, 2019. DOI: 10.1016/j.devcel.2018.12.018.