A recent study found that nearly 18 percent of patients diagnosed with multiple sclerosis before being referred to two major Los Angeles medical centers for treatment actually had been misdiagnosed with the autoimmune disease.

The retrospective study, led by investigator Marwa Kaisey, MD, along with Nancy Sicotte, MD, interim chair of Neurology and director of the Cedars-Sinai Multiple Sclerosis and Neuroimmunology Center, and researchers from UCLA and the University of Vermont, analyzed the cases of 241 patients who had been diagnosed by other physicians and then referred to the Cedars-Sinai or UCLA MS clinics over the course of a year.

Investigators sought to determine how many patients were misdiagnosed with MS, and identify common characteristics among those who had been misdiagnosed.

“The diagnosis of MS is tricky. Both the symptoms and MRI testing results can look like other conditions, such as stroke, migraines and vitamin B12 deficiency,” Kaisey said. “You have to rule out any other diagnoses, and it’s not a perfect science.”

The investigators found that many patients who came to the medical centers with a previous diagnosis of MS did not fulfill the criteria for that diagnosis. The patients spent an average of four years being treated for MS before receiving a correct diagnosis.

“When we see a patient like that, even though they come to us with an established diagnosis, we just start from the beginning,” Sicotte said.

The most common correct diagnosis was migrane (16 percent), followed by radiologically isolated syndrome, a condition in which patients do not experience symptoms of MS even though their imaging tests look similar to those of MS patients. Other correct diagnoses included spondylopathy (a disorder of the vertebrae) and neuropathy (nerve damage).

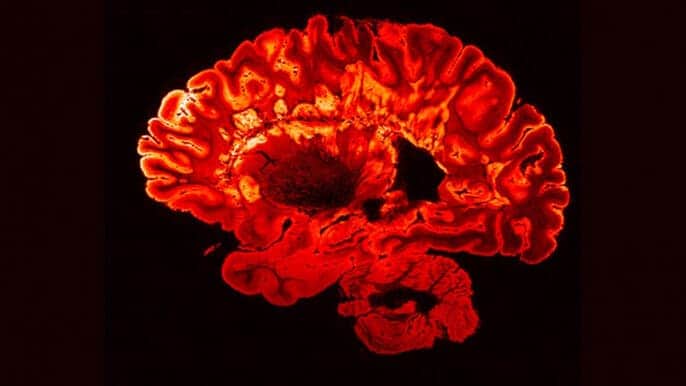

Among those misdiagnosed, 72 percent had been prescribed MS treatments. Forty-eight percent of these patients received therapies that carry a known risk of developing progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, a serious disease in the white matter of the brain, caused by viral infection.

“I’ve seen patients suffering side effects from the medication they were taking for a disease they didn’t have,” Kaisey said. “Meanwhile, they weren’t getting treatment for what they did have. The cost to the patient is huge–medically, psychologically, financially.”

Investigators estimated that the unnecessary treatments identified in this study alone cost almost $10 million.

The investigators hope that the results of this study, which will be published in May’s issue of the peer-reviewed journal Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders, along with recently funded research into new biomarkers and improved imaging techniques, will help improve diagnostic procedures and help prevent future MS misdiagnoses.

Funding for the new research includes $60,000 from Cedars-Sinai Precision Health, a partnership among scientists, clinicians and industry designed to advance personalized medicine. Kaisey said that she hopes these studies will also lead to better availability of treatment for patients who do have the disease.

“The first step, which is what we’ve done here, is to identify the problem, so now we’re working on potential solutions,” she said.