More than 60 years ago, British physician Denis Parsons Burkitt and his associates achieved one of the signal successes in cancer medicine when they cured children in sub-Saharan Africa with a form of lymphoma by treating them with high doses of the chemotherapy drug cyclophosphamide. Now, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute researchers have shown that the traditional understanding of the drug’s mode of action is incomplete.

In a paper in today’s issue of the journal Cancer Discovery, the researchers demonstrate that large doses of cyclophosphamide not only kill cancer cells directly, as has been known, but also spur an immune system attack on the cells. The discovery resolves long-standing questions about how cyclophosphamide and other alkylating agents – among the oldest and most widely used types of chemotherapy – work, and suggests a novel way of sparking an immune system strike on certain cancers.

“Our results show that, at high doses, cyclophosphamide and other alkylating agents blur the line between chemotherapy and immunotherapy,” said Dana-Farber’s David Weinstock, MD, the senior author of the study. “These findings offer insights into how to switch on key immune system cells to augment existing therapies.”

Cyclophosphamide was just the eighth anti-cancer drug to enter standard therapy when it was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 1954. It became a mainstay of cancer treatment after Burkitt and others used high doses to cure children with what’s now known as Burkitt lymphoma – which had a 100% mortality rate at the time – sometimes with only one dose. Cyclophosphamide and other alkylating agents are now used at lower doses to treat many types of cancer, including breast, ovarian, and pediatric cancers.

Alkylating agents work by attaching chemical components called alkyl groups to cancer cells’ DNA, leading to breaks in the DNA molecule. The damage undermines the cells’ ability to duplicate their DNA and, ultimately, to divide.

Over the years, clues emerged that there’s more to the drugs’ effectiveness than damaging DNA. Researchers discovered, for example, that while high doses are much more effective against certain cancers than low doses, they inflict about the same amount of DNA damage, suggesting that something else comes into play at high doses. Sporadic data pointed to the immune system.

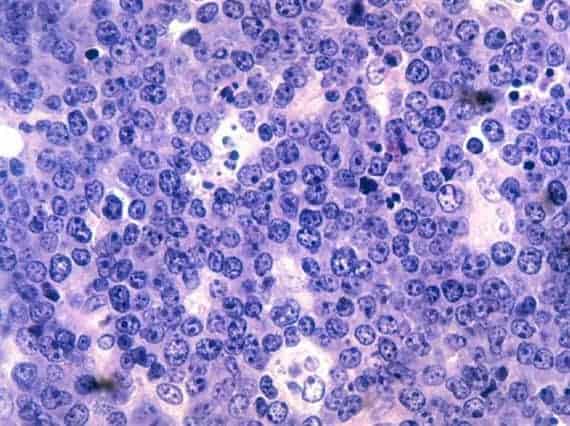

Another clue came from pathology studies of Burkitt lymphoma tissue. “Burkitt lymphoma and other high-grade lymphomas with rearrangements in the MYC gene have a ‘starry sky’ appearance under the microscope, with large numbers of macrophages [a type of immune system cell] dispersed among the lymphoma cells,” Weinstock remarked.

In the new study, investigators focused on the effect of high doses of cyclophosphamide on macrophages – cells that, under the right conditions, eat infected cells or cells in the process of dying. In mouse models implanted with human lymphoma tissue, the researchers showed that high doses of the drug, but not normal doses, damaged tumor cells in a way that severely stressed the lymphoma cells. The stressed cells responded by secreting cytokines, substances that summon macrophages to eat the tumor cells.

The researchers analyzed thousands of these macrophages to determine which genes were active, or expressed, in each of them. They found that one subset, which expresses the proteins CD36 and FcgRIV, has a particularly voracious appetite for stressed lymphoma cells. Dubbed “super-macrophages,” they devour lymphoma cells, Weinstock said.

Although high doses of cyclophosphamide and other alkylating agents may be too toxic for patients with diseases other than Burkitt lymphoma, researchers are investigating agents that mimic their ability to stress cancer cells, but with milder side effects.

The findings may be especially relevant for the treatment of “double-hit” lymphomas, which are marked by their aggressiveness and for a rearrangement in the MYC gene, Weinstock observed. Targeted therapies are currently lacking for this disease, which accounts for six to 10% of diffuse large B cell lymphomas and generally has poor outcomes for patients.