Fossil animal droppings, charcoal from ancient fires and bone fragments litter the ground of one of the world’s most important human evolution sites, new research reveals.

The latest evidence from southern Siberia shows that large cave-dwelling carnivores once dominated the landscape, competing for more than 300,000 years with ancient tribes for prime space in cave shelters.

A team of Russian and Australian scientists have used modern geoarchaeological techniques to unearth new details of day-to-day life in the famous Denisova Cave complex in Siberia’s Altai Mountains.

Large carnivores such hyena, wolves and even bears and at least three early nomadic human groups (hominins) – Denisovans, Neanderthals, and early Homo sapiens – used this famous archaeological site, the researchers say in a new Scientific Reports study examining the dirt deposited in the cave complex over thousands of years.

“These hominin groups and large carnivores such as hyenas and wolves left a wealth of microscopic traces that illuminate the use of the cave over the last three glacial-interglacial cycles,” says lead author, Flinders University ARC Future Fellow Dr Mike Morley.

“Our results complement previous work by some of our colleagues at the site that has identified ancient DNA in the same dirt, belonging to Neanderthals and a previously unknown human group, the Denisovans, as well as a wide range of other animals”.

But it now seems that it was the animals that mostly ruled the cave space back then.

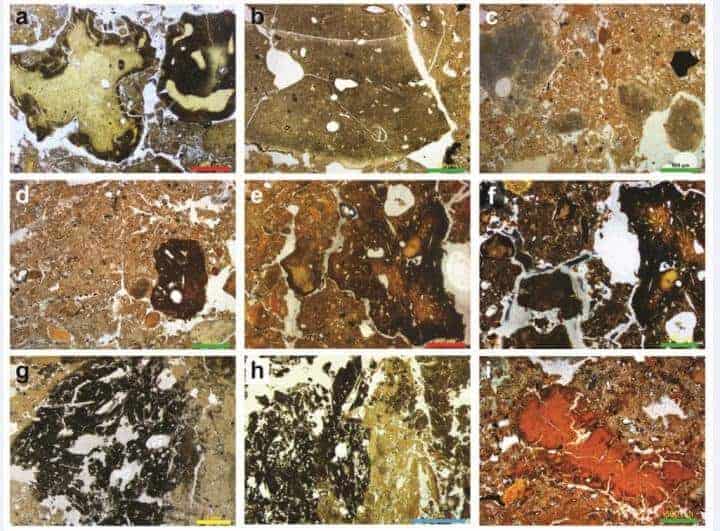

Microscopic studies of 3-4 metres of sediment left in the cave network includes fossil droppings left by predatory animals such as cave hyenas, wolves and possibly bears, many of their kind made immortal in ancient rock art before going extinct across much of Eurasia.

From their ‘micromorphology’ examination of the dirt found in Denisova Cave, the team discovered clues about the use of the cave, including fire-use by ancient humans and the presence of other animals.

The study of intact sediment blocks collected from the cave has yielded information not evident to the naked eye or gleaned from previous studies of ancient DNA, stone tools or animal and plant remains.

Co-author of the new research, University of Wollongong Distinguished Professor Richard (Bert) Roberts, says the study is very significant because it shows how much can be achieved by sifting through sedimentary material using advanced microscopy and other archaeological science methods to find critical new evidence about human and non-human life on Earth.

“Using microscopic analyses, our latest study shows sporadic hominin visits, illustrated by traces of the use of fire such as miniscule fragments, but with continuous use of the site by cave-dwelling carnivores such as hyenas and wolves,” says Professor Roberts.

“Fossil droppings (coprolites) indicate the persistent presence of non-human cave dwellers, which are very unlikely to have co-habited with humans using the cave for shelter.”

This implies that ancient groups probably came and went for short-lived episodes, and at all other times the cave was occupied by these large predators.

The Siberian site came to prominence more than a decade ago with the discovery of the fossil remains of a previously unknown human group, dubbed the Denisovans after the local name for the cave.

In a surprising twist, the recent discovery of a bone fragment in the cave sediments showed that a teenage girl was born of a Neanderthal mother and Denisovan father more than 90,000 years ago.

Denisovans and Neanderthals inhabited parts of Eurasia until perhaps 50,000 to 40,000 years ago, when they were replaced by modern humans (Homo sapiens).