Two trillion times each day, the cells in a typical human divide to replace old, damaged or dead cells. Before a cell divides, though, it makes an exact copy of its DNA, which will be passed on to the new cells.

To start the copying process, the DNA double helix unwinds so each strand can serve as a template for the new DNA. Scientists refer to the unwound DNA as a replication fork because the two strands resemble a two-tined fork. As this highly complex replication process progresses, the two strands of the original DNA can break or be damaged thousands of times.

“Obstacles that slow or stall replication forks occur naturally or can result from environmental factors like exposure to UV light,” said Jennifer Mason, an assistant professor of genetics and biochemistry in the Clemson University College of Science. “They’re actually a pretty big assault on the cell, which is why the cells have elaborate mechanisms to make sure the replication process is protected.”

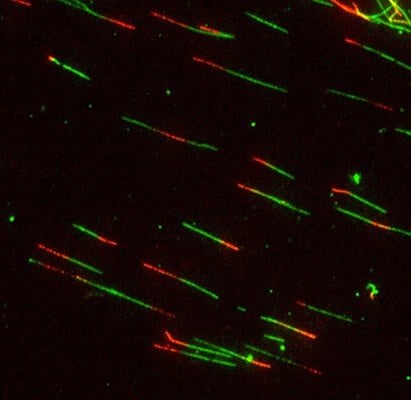

Emerging evidence indicates that a pathway to repair DNA breaks, known as homologous recombination (HR), has additional break-independent roles at stalled replication forks. A key factor in HR is a protein called RAD51, which binds to the single DNA strand at the broken end and backs up the forks by converting them into a structure that resembles a chicken foot — a process known as fork regression.

In a recent study, Mason created a mutated version of RAD51 to better understand its critical functions at stalled replication forks.

“We made a recombination-defective RAD51 variant that can still bind DNA, but it cannot search for the intact copy of DNA or perform strand exchange,” Mason said. “The more we understand the process, the more likely we are to figure out how it goes wrong in cancer and we can help with improved treatment strategies down the road.”

In her study, which was recently published online in Nature Communications, Mason discovered RAD51’s strand exchange activity is not required for fork regression, but is important to restart replication once the obstacle has been removed.

“The field wants to figure out what role this pathway has in cancer and what each of the players are doing,” Mason said. “This study provides a missing piece in a very big puzzle that we are still trying to figure out.”

In the short term, Mason said, other scientists in the cancer biology field can apply the mutated RAD51 gene to their own research to help unravel the replication process further and better understand how breaks are repaired.

Mason’s co-author on the paper is Douglas Bishop, a faculty member at the University of Chicago and Mason’s former post-doctoral research adviser. The full title of the paper is “Non-enzymatic roles of human RAD51 at stalled replication forks.”

This work was funded by the National Institutes of Health grants GM50936 to D.K.B., CA205518-01 to D.K.B. The researchers are wholly responsible for the content of this study, of which the funders had no input.