Open relationships typically describe couples in which the partners have agreed on sexual activity with someone other than their primary romantic partner, while maintaining the couple bond. Can these open relationships work? It depends, concludes a team from the University of Rochester that focuses on couples research. Not surprisingly, the success of such relationships hinges on solid communication between all parties involved.

“We know that communication is helpful to all couples,” says Ronald Rogge, an associate professor of psychology and head of the Rogge Lab, where the research was conducted. “However, it is critical for couples in nonmonogamous relationships as they navigate the extra challenges of maintaining a nontraditional relationship in a monogamy-dominated culture. Secrecy surrounding sexual activity with others can all too easily become toxic and lead to feelings of neglect, insecurity, rejection, jealousy, and betrayal, even in nonmonogamous relationships.”

Past studies have attempted to gauge the success of nonmonogamous relationships. But the critical difference this time is that the Rochester team considered distinctions and nuances within various types of nonmonogamous relationships, and then assessed the success of each type independently. As a result, their findings draw no blanket conclusions about the prospects of nonmonogamous relationships; instead, the research, published in the Journal of Sex Research, suggests conditions under which nonmonogamous relationships tend to succeed, and those under which relationships become strained.

Rogge–together with his former undergraduate research assistant, Forrest Hangen ’19, now a graduate student at Northeastern University; and Dev Crasta ’18 (PhD), now a post-doctoral fellow at the Canandaigua VA Medical Center and the University of Rochester Medical Center’s Department of Psychiatry–analyzed responses from 1,658 online questionnaires. Among the respondents a majority (67.5 percent) was in their 20s and 30s, 78 percent of participants were white, nearly 70 percent identified as female, and most were in long-term relationships (on average nearly 4 ½ years). The team assessed three key dimensions for each relationship–applying what they call the “Triple-C Model” of mutual consent, communication, and comfort.

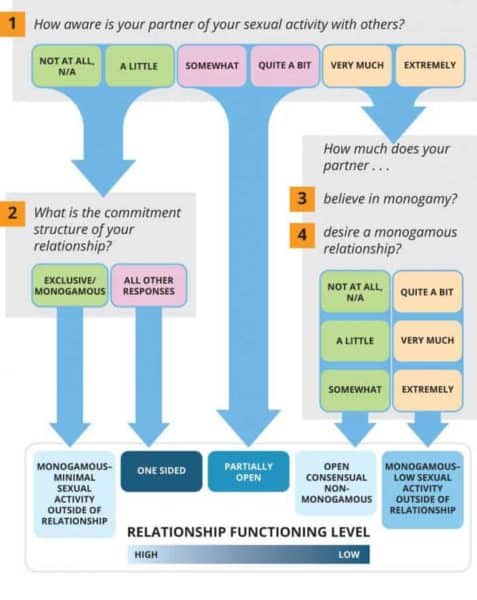

Significantly, they divided study participants into five distinct classes of relationships:

- Two monogamous groups, representing earlier- and later-stage monogamous relationships

- Consensual nonmonogamous (CNM) relationships, marked by low interest in monogamy and high levels of mutual consent, comfort, and communication around commitment and sexual activity with a person other than the primary partner

- Partially open relationships, with more mixed attitudes toward monogamy and lower consent, comfort, and communication

- One-sided sexual relationships with a person besides the primary partner, in which one partner desires monogamy while the other partner engages in sex outside the existing relationship with low levels of mutual consent, comfort, and almost no communication between the couple about sex outside the relationship.

The findings

The team discovered that monogamous and consensual nonmonogamous (CNM) groups demonstrated high levels of functioning in their relationships and as individuals, whereas the partially open and one-sided nonmonogamous groups exhibited lower functioning.

People in both monogamous groups reported relatively healthy relationships, as well as some of the lowest levels of loneliness and psychological distress. Both monogamous groups and the consensual nonmonogamous group (CNM) reported similarly low levels of loneliness and distress, and similarly high satisfaction levels in regards to need, relationship, and sex.

Moreover, both monogamous groups reported the lowest levels of sexual sensation seeking, indicating fairly restrained and mainstream attitudes towards casual sex.

Overall, people in the three nonmonogamous relationships reported high levels of sexual sensation seeking, were more likely to actively look for new sexual partners, and to have contracted a sexually transmitted disease.

Yet, each of the three nonmonogamous groups varied in significant ways.

People in the consensual nonmonogamous group (CNM) were in fairly long-term relationships (and had the highest proportion among all five groups of people living with their partner, followed closely by the monogamous group with minimal recent sex outside their relationship).

The consensual nonmonogamous group also had the highest number of heteroflexible (primarily heterosexual but open to sex with same-sex partners) and bisexual respondents, suggesting that individuals in the LGBT community might be more comfortable with non-traditional relationship structures.

By contrast, people in partially open and one-sided nonmonogamous relationships tended to be in younger relationships, reported lower levels of dedication to their relationships, and low levels of affection. Few reported high sexual satisfaction, and they had the highest rates of condomless sex with new partners.

The groups of partially open and one-sided nonmonogamous relationships also showed some of the highest levels of discomfort with emotional attachment (also called attachment avoidance), psychological distress, and loneliness.

Overall, the one-sided group fared worst of all, with the highest proportion of people significantly dissatisfied with their relationships: 60 percent–nearly three times as high as the monogamous or the consensual nonmonogamous group.

Rogge cautions that the authors looked at cross-sectional data only, which meant they were unable to directly track relationships failing over time.

While the data clearly show that not all nonmonogamous relationships are equal–one rule applies to all:

“Sexual activity with someone else besides the primary partner, without mutual consent, comfort, or communication can easily be understood as a form of betrayal or cheating,” says Hangen. “And that, understandably, can seriously undermine or jeopardize the relationship.”