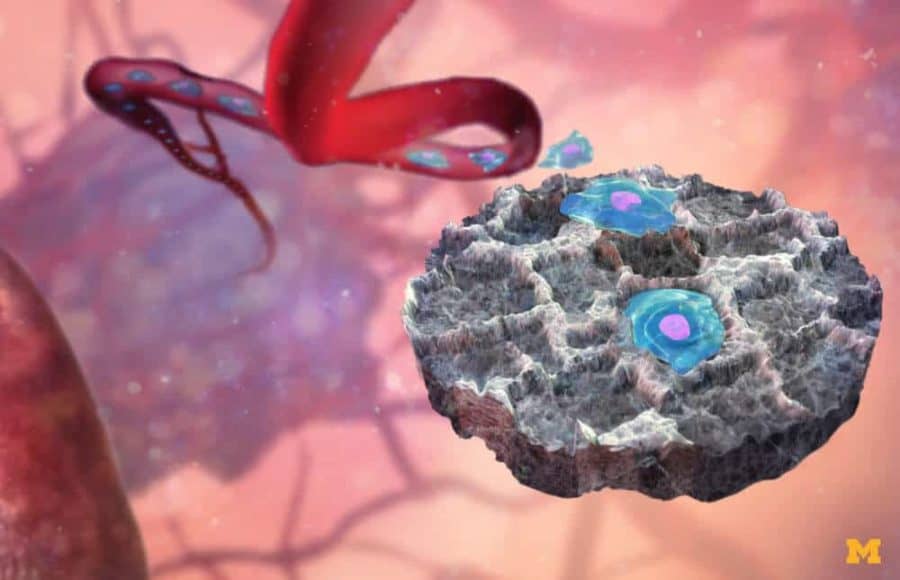

Invasive procedures to biopsy tissue from cancer-tainted organs could be replaced by simply taking samples from a tiny “decoy” implanted just beneath the skin, University of Michigan researchers have demonstrated in mice.

These devices have a knack for attracting cancer cells traveling through the body. In fact, they can even pick up signs that cancer is preparing to spread, before cancer cells arrive.

“Biopsying an organ like the lung is a risky procedure that’s done only sparingly,” said Lonnie Shea, the William and Valerie Hall Chair of biomedical engineering at U-M. “We place these scaffolds right under the skin, so they’re readily accessible.”

The ease of access would also allow doctors to monitor the effectiveness of cancer treatments closer to real time.

The U-M team’s most recent work appears in Cancer Research, a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research.

Biopsies of the scaffold allowed researchers to analyze 635 genes present in the captured cancer cells. From these genes, the team identified ten that could predict whether a mouse was healthy, if it had a cancer that had not begun to spread yet, or if a cancer was present and had begun to spread. They could do that all without the need for an invasive biopsy of an organ.

The gene expression obtained at the scaffold had distinct patterns relative to cells from the blood, which are obtained through a technique known as liquid biopsy. These differences highlight that the tissue in these traps provides unique information that correlates with disease progression.

The researchers have demonstrated that the synthetic scaffolds work with multiple types of cancers in mice, including pancreatic cancer. They work by luring immune cells, which, in turn, attract cancer cells.

“When we started off, the idea was that we would biopsy the scaffold and look for tumor cells that had followed the immune cells there,” Shea said. “But we realized that by analyzing the immune cells that gather first, we can detect the cancer before it’s spreading.”

In treating cancer, early detection is key.

“Currently, early signs of metastasis can be difficult to detect,” said Jacqueline Jeruss, an associate professor of surgery and biomedical engineering and a co-author of the study. “Imaging may be done once a patient experiences symptoms, but that implies the number of cancer cells may already be substantial. Improved detection methods are needed to identify metastasis at a point when targeted treatments can have a significant beneficial impact on slowing disease progression.”

The immune cells allowed researchers to identify whether treatments were effective in the mice and which subjects were sensitive or resistant to treatment.

The decoy’s ability to draw immune and cancer cells can also bolster the treatment itself. In previous research, the devices demonstrated an ability to slow the growth of metastatic breast cancer tumors in mice, by reducing the number of cancer cells that can reach those tumors.

In the future, Shea envisions that the scaffolds could be outfitted with sensors and Bluetooth technology that could deliver information in real time without the need for a biopsy.

The work was supported by the National Institutes of Health.