Pancreatic cancer is one of the most lethal diseases afflicting humans. Although it accounts for about 3% of all cancer diagnoses, the most recent data indicate that pancreatic cancer may soon become the leading cause of cancer-related deaths. On top of that, the percentage of people with the disease has been growing over the last decade.

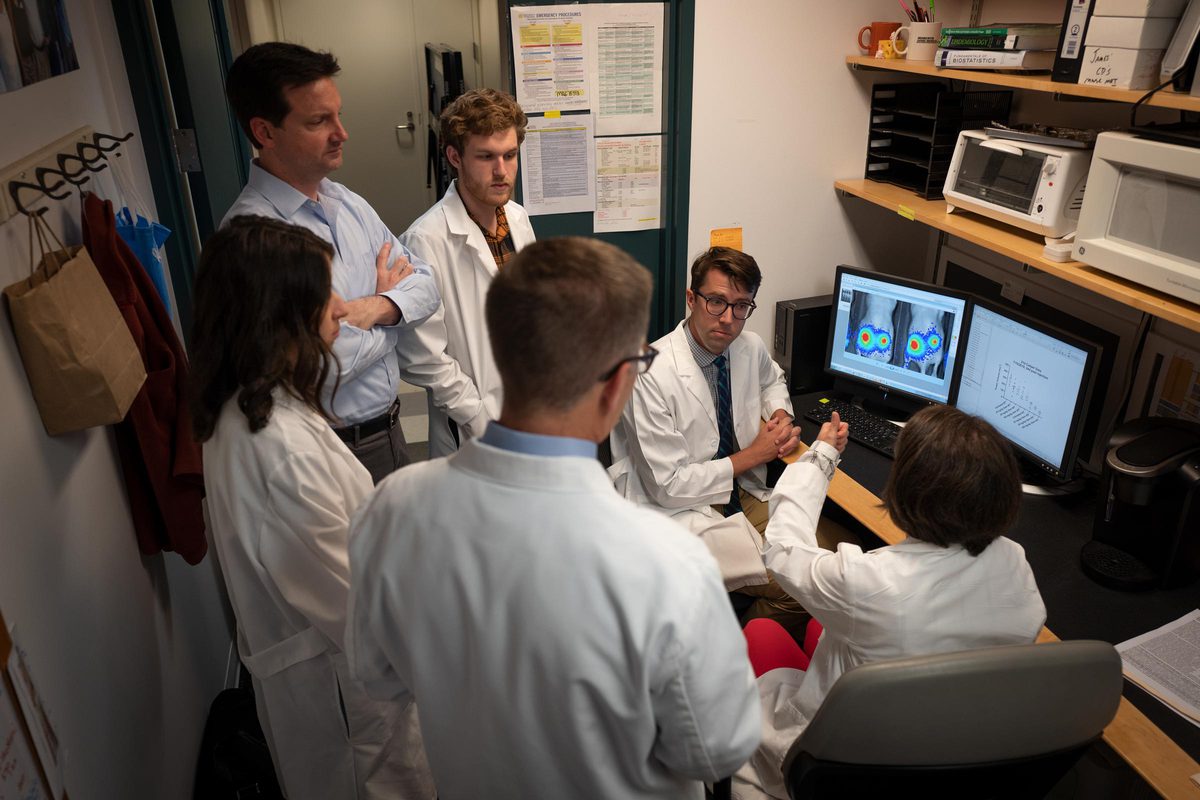

Matthew J. Lazzara, an associate professor of chemical engineering at the University of Virginia’s School of Engineering, and researchers in his lab are devising a better way to treat the disease following the award of a five-year, $2.34 million grant from the National Cancer Institute as part of its Cancer Systems Biology Consortium. The consortium is an initiative focused on bringing together multidisciplinary teams to investigate the complexity of cancer research.

There is urgency to Lazzara’s work. Current treatments include dosing patients with brutal, often-debilitating amounts of chemotherapy and radiation. In a unique multi-institutional, multidisciplinary collaboration, Lazzara’s group is teaming with Ben Stanger, the Hanna Wise Professor in Cancer Research at the University of Pennsylvania; Babatunde Ogunnaike, a University of Delaware process control expert and professor of chemical engineering; and Dr. Todd Bauer, UVA Health’s director of surgical oncology and a pancreatic cancer expert.

Part of what makes pancreatic cancer so deadly is that it is hard to diagnose at an early stage, and symptoms are often masked by other ailments. Pancreatic tumors shed their killer cells easily, metastasizing quickly to the rest of the body.

In addition to metastasis, tumors often wind around arteries in the pancreas. Because of these issues, surgery isn’t an option in most cases, although removing the tumor is the only known cure. Chemotherapy is also difficult because the cancer can tolerate typical doses with impunity, and treatment regimens may only extend life for a short – and often miserable – period of time.

Patients are left with few options. For the thousands of people diagnosed with pancreatic cancer annually, time is of the essence for finding better treatments.

Lazzara and his team are studying the cell-signaling pathways that transmit information to cancer cells from many different sources simultaneously. These signals may influence a cell to divide, migrate, die or resist therapy.

“There are quantitative rules about that process, and we’re trying to decipher what those rules are,” Lazzara said. “We are on the threshold of quantitatively understanding how signaling pathways actually dictate what a cell will do in one context or another.

“What happens often in cancer is that a gene is mutated or over-expressed in a way that changes the way those signals are generated. And that then changes what a cell decides to do. It proliferates out of control or migrates when it’s not supposed to, and often becomes extremely resistant to chemotherapy.”

Stanger, co-investigator on the project, said cancers can outsmart drug regimens given to patients to fight the disease. “The goal of the grant is to understand the signals that underlie ‘plasticity,’ the capacity of cancer cells to change their properties to evade the anti-tumor effects of chemotherapy.”

At the University of Delaware, Ogunnaike develops and analyzes engineering control systems.

“There are certain drugs that have an effect on pancreatic cancer. Which ones to use, how much of each and when to apply them to the patient can be formulated in the form of an optimal control problem and solved using mathematical models,” Ogunnaike said. “My role in this project is to develop the mathematical models and apply principles of optimal control theory to determine the amount and timing of the therapeutics that Matt has identified as potential treatments.”

The research team is compiling tremendous amounts of data around what influences cell signaling and decision-making in pancreatic cancer. They feed that data into a model and use machine learning to look for unique patterns that might explain what they see happening. They are specifically looking at cells that decide to undergo a process called epithelial-mesenchymal transition, in which cells become migratory and invasive. In pancreatic cancer, these cells also become more resistant to chemotherapy.

“We think we’ve identified some of the pathways that regulate this transition to a more chemo-resistant state, and we think it may be possible to drug the cells back to an epithelial state, which will make them more sensitive to chemotherapy,” Lazzara said. “The extra piece of this grant, which I think made it attractive to the National Institutes of Health, is that after identifying which combination of drugs to use, we’re going to use a different kind of computational modeling to figure out how best to combine those drugs to minimize toxicity for patients.”

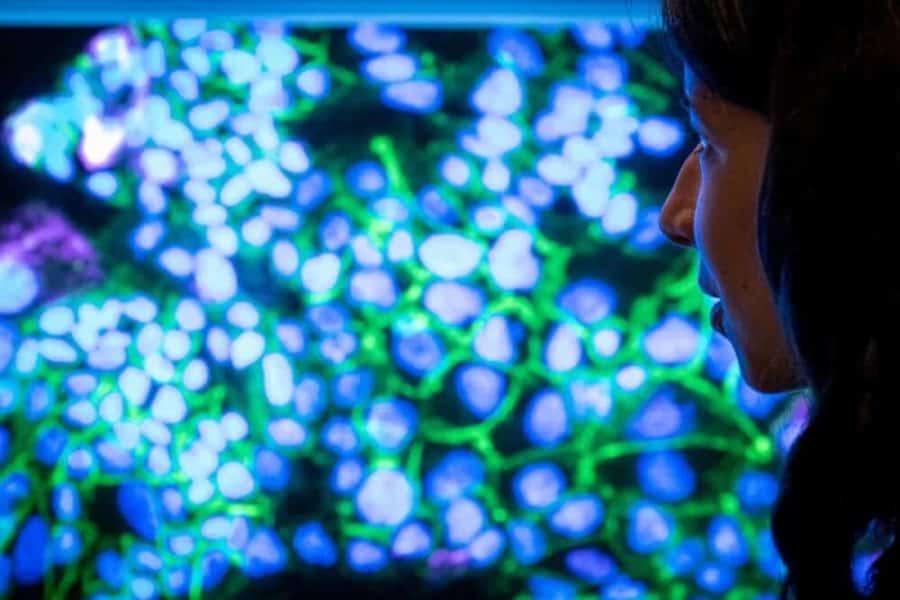

His team of researchers are hard at work. In Lazzara’s lab, Ph.D. student and National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellow Brooke McGirr is analyzing pancreatic cells in sections of tumors grown in mice. Her research focuses on the cell-signaling processes regulated by the complex tumor microenvironment that drive epithelial-mesenchymal transition.

“I’m fascinated by the development of novel therapeutic regimens to give people hope and a better life,” she said. “I was drawn to work with Professor Lazzara because he works at the intersection of quantitative problem-solving and complex challenges in cancer biology.”

As part of the collaborative research, Bauer and his group are developing state-of-the-art model systems for use in the study.

“My laboratory has established a human pancreatic cancer tissue bank from our UVA patients who have undergone surgery of their pancreatic cancer,” Bauer said. “We will use our mouse models of human pancreatic cancer with these patient-derived pancreatic cancer cells implanted in the mouse pancreas to test approaches at inhibiting epithelial-mesenchymal transition in combination with chemotherapy.”

This dynamic collaboration of scientists from different disciplines is important for solving complex problems, Ogunnaike said. “I don’t know of any problem of significance today that can be solved by one individual. The same is true for the problem we are tackling in this project. It requires collaboration across many disciplines.”

Stanger agreed. “Coming at a problem from such different directions poses its own challenges, since we speak different languages, but it also provides an opportunity for fresh and unanticipated insights. This possibility lies at the center of science – not to confirm what we already think we know, but to see something we didn’t know existed.”

Bauer believes the impact of this collaborative work could be significant for patients. “We anticipate that this project will lead to novel therapies for pancreatic cancer, which are desperately needed, and will uncover new information about the process of epithelial-mesenchymal transition in pancreatic cancer.”

The group is moving toward pre-clinical trials now and hopes to be able to design a clinical study within the period of this grant.

“There’s a sense of urgency about it, because people are not living long once they’re diagnosed with this disease,” Lazzara said. “The National Institutes of Health is looking for people to bridge across disciplines and come up with new approaches. That’s what we are doing.”