The world’s love for chocolate has helped decimate protected forests in western Africa as some residents have turned protected areas into illegal cocoa farms and hunting grounds.

But an international group of researchers has found that simply patrolling the grounds of two forest reserves in Ivory Coast has helped reduce illegal activity by well more than half between 2012 and 2016.

The researchers themselves were among those who conducted the foot patrols, said W. Scott McGraw, professor of anthropology at The Ohio State University and co-author of a recent paper in Tropical Conservation Science documenting their success.

McGraw said that on patrols he participated in, farmers tending illegal cocoa crops were often surprised that anyone approached them and told them to stop their activities.

“They just weren’t used to encountering anyone who put up any kind of resistance. We told them they weren’t allowed to be growing cocoa there and they would respond that ‘no one has ever told us we couldn’t,’” he said.“It was just so blatant.”

McGraw conducted the study with Sery Gonedelé Bi, Eloi Anderson Bitty and Alphonse Yao of the University Félix Houphouët Boigny in Ivory Coast.

Forest loss is a major problem in Ivory Coast. Between 2000 and 2015, the country lost about 17 percent of its forest cover, driven by an annual deforestation rate – 2.69 percent – that was among the highest in the world, according to Global Forest Watch.

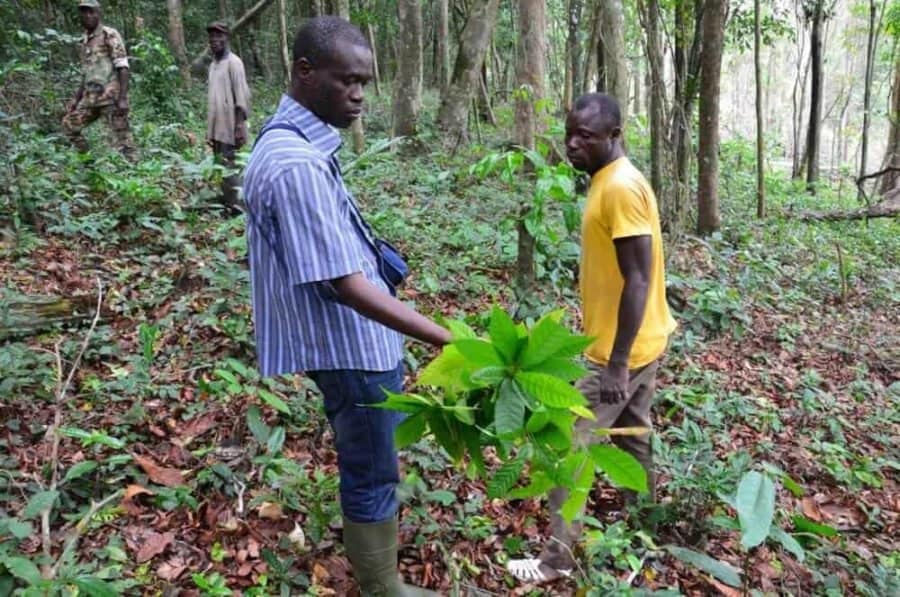

Much of that forest was cleared for cocoa farms to meet the growing demand for chocolate worldwide. The destruction of the forests – as well as the illegal poaching found in this study – threaten several critically endangered primates that live in these reserves, McGraw said. A previous study by McGraw and his colleagues documented the threat to primates.

The researchers conducted this study in the Dassioko Sud and Port Gauthier forest reserves along the Atlantic coast.

Regular patrols were carried out three to four times a month in both reserves between July 2012 and June 2016. Each team usually consisted of six to eight people, including the researchers, law enforcement officials (occasionally) and community members recruited from neighboring towns and paid with funds from several conservation organizations.

The patrol teams would normally go out for seven hours at a time, taking random routes so as to not be predictable. They noted the time and direction of all gun shots, collected discarded gun cartridges, and counted and dismantled all snares used to capture monkeys and other game.

They recorded the size and location of all logging and farming operations and destroyed all plantation crops, most of which were new cocoa seedlings.

When the patrols included law enforcement personnel, they would arrest poachers, as well as loggers and illegal farmers.

McGraw said he was never on one of the rare patrols that encountered a poacher with a gun, although his co-authors were.

“I was told those were the most tense situations. That is not a standoff that I would want to be a part of,” he said.Altogether, during the four years of the study, the patrol teams apprehended six poachers, heard 302 gunshots, deactivated 1,048 snares and destroyed 515 hectares of cocoa farms.

But the good news is that the number of these illegal activities dropped dramatically over the years they patrolled. For example, the researchers documented about 140 signs of illegal activity (such as shotgun shells, snares or cocoa plantings) at Port Gauthier Forest Reserve in August 2012. In June 2016, there were fewer than 20. Similar reductions in illegal activities were recorded in Dassioko Sud Forest Reserve.

The patrol activities weren’t responsible for all the decline, McGraw said. For example, a portion of the poaching decline could have been related to the 2014 Ebola outbreak, which reduced demand for bushmeat.

But much of the decline in illegal activities in the reserves occurred before 2014, he noted.

Regular patrols in the two reserves have not continued since 2016, McGraw said. Surveys since then suggest that the gains made by the patrols are holding and illegal activities have not returned to their previous highs.

“That said, I think it is important that there is a renewed effort to patrol these reserves. We need something sustained,” he said.

“We need Ivorian officials to take a stronger stand against illegal activities in the country’s protected areas.”

This research was funded by Conservation International, Primate Conservation, Inc., and Rainforest Rescue.