Don’t expect a straightforward answer from Chanan Tigay about the authenticity or even the existence of what was promoted as the earliest version of the fifth and final book of the Jewish Torah, known to Christians as the Book of Deuteronomy in the Old Testament.

As an author who spent years trying to unravel a juicy mystery and get it down on paper, Tigay wants you to read his book, “The Lost Book of Moses: The Hunt for the World’s Oldest Bible,” to find the answer. But at a talk on Wednesday, the writer, journalist, and fellow at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study offered listeners an enticing peek, describing how he landed on the story of the mysterious manuscript and about his years trying to track down the document — which, if proven authentic, would’ve shaken biblical scholarship as it indicated that “the Torah had changed and possibly … had been changed by human hands,” challenging claims of divine authorship, Tigay said.

From the author’s description, it was a wild, Indiana Jones-type ride that included a competition to find the relic, false starts, dead ends, trips to far away places, and an ultimate breakthrough close to home. And it came about by chance. When Tigay mentioned at dinner one night several years ago that he was writing an article about an alleged discovery of Noah’s Ark, his father, a rabbi and Biblical scholar whose expertise is the study of Deuteronomy, told him the story of Moses Wilhelm Shapira, an antiquities dealer from Jerusalem who had found what he claimed was an important biblical artifact in the late 19th century.

Tigay was hooked. In an interview from 2016 when his book was first published, he said that his obsession with Shapira grew until he “ended up falling in love with the guy … it was like I was dating this long-dead man, which was awkward, for my wife especially.”

But in a way, it was understandable. Shapira was a rogue, a charmer, a largely self-taught scholar who craved legitimacy in the eyes of the academy, Tigay said. In 1883, he appeared on the doorstep of the British Museum requesting an astronomical sum for an ancient Hebrew text he described as the world’s oldest Bible scroll. Shapira’s reputation was somewhat mixed, and skeptical museum officials enlisted a Bible scholar to examine the find. The expert found “changes, omissions and additions to the traditional texts,” and radical alterations “to the Ten Commandments,” said Tigay, which had been “altered, moved around and added to.” In the end, the manuscript was deemed a fake, and a year later a humiliated Shapira took his life in Rotterdam at the age of 54.

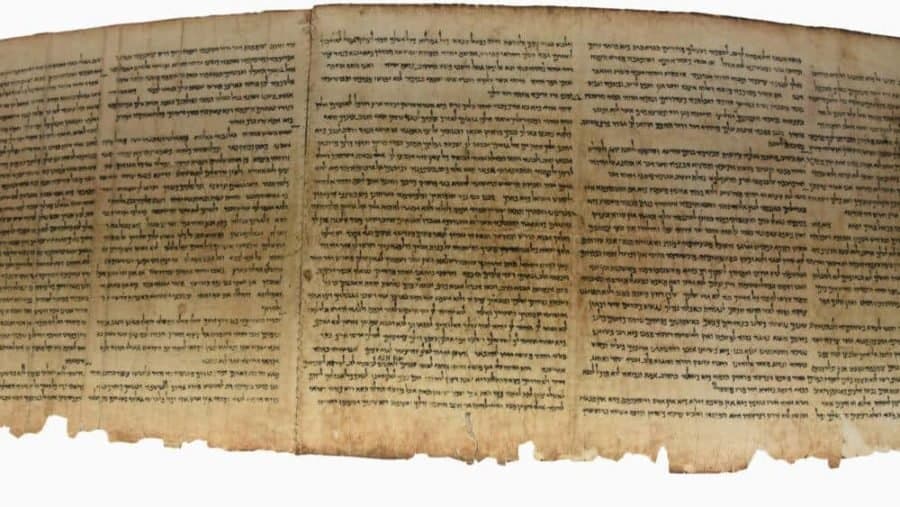

The story might have ended there, except for the fact that 60 years later a Bedouin shepherd stumbled upon several ancient scrolls in a cave near the Dead Sea in the same general area where Shapira said his manuscript had been found. Many considered the newly discovered scrolls to be “the greatest archaeological discovery of the 20th century,” said Tigay, who during his Radcliffe fellowship is working on a book about antiquities looting in the Middle East after the Arab Spring uprising.

To Tigay and others, the similarities between Shapira’s manuscript and the Dead Sea Scrolls were unmistakable.

“Recall now that Shapira’s Deuteronomy was said to have been discovered in a cave, so too were the Dead Sea Scrolls. Shapira’s manuscript was full of departures from the traditional Biblical text, so too were the Dead Sea Scrolls. Shapira’s strips were found by Bedouins wandering the desert near the Dead Sea, so too were the Dead Sea Scrolls. Shapira’s manuscript was a copy of Deuteronomy. Among the Dead Sea Scrolls, Deuteronomy was the second most numerous book after Psalms.

“Indeed, the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls six decades after Shapira’s death have led some scholars to reopen the investigation of his strange Deuteronomy whose dismissal all those years earlier might have been tragically premature,” said Tigay. “It was even possible that Shapira had found the first Dead Sea Scroll 60 years before the rest. But there was a problem. In the 62 years between Shapira’s death and the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls, Shapira’s Deuteronomy had mysteriously disappeared.”

Tigay decided to try to find them. His travels took him to Israel, Germany, France, and the Netherlands, to “hidden storerooms in the Louvre,” “musty English attics,” and to a flooded gorge in Jordan where the scrolls were supposedly found. But after years of looking and with a book deadline looming, he was flailing. “I had no ending. I hardly had a beginning,” said Tigay. Then came a cryptic email from a stranger in Sydney, claiming to know the name of the person who came into possession of Shapira’s manuscript after they were thought to have disappeared. The note led Tigay on another trip halfway around the world.

“I am happy to take any questions there are,” Tigay told the Radcliffe crowd after his prepared talk, “except for one.”

Though the author stopped short of giving away the ending, he did offer insight into his process and his approach. “I was writing a book that I wanted people to feel like they couldn’t put down” he said. “I wanted it to feel like a mystery … in the end to me, it seemed like a great caper.”

And somewhat surprisingly, he told his audience, as time went on he found himself partly hoping to learn that the scrolls were a hoax.

“Even if it was completely fake from A to Z it was so creative, and so weird and ended up predicting the Dead Sea Scrolls, which no one had even fathomed at the time … the idea that [Shapira] might have come up with this thing on his own, out of his own mind, he would have been some kind of genius. It is so clever and so devious and so creative. And so by the end of this I found myself in some ways hoping that it was fake because that would speak volumes about the man.”