Duke University researchers exploring the sensation and management of pain have captured the shape, in unprecedented detail, of a biological structure in the mouth, nose and throat that senses pungent, irritating chemicals.

Their new map of “the wasabi sensor” appears Dec. 19 in the journal Neuron.

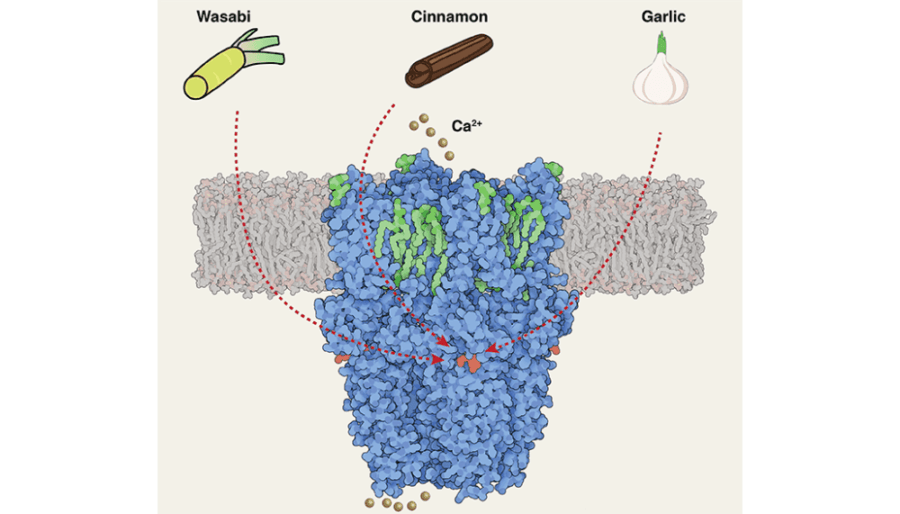

The sensor, called TRPA1, is from a family of transient receptor potential channels, or TRP, that have been studied intensively as drug targets for pain and inflammation. The researchers jokingly call this one the wasabi sensor because of its sensitivity to chemical irritants, like the hot Japanese condiment. It’s the signaling spot for tear gas too.

There are at least 30 different kinds of TRP, specialized to sense pain, itch, heat, cold, and other sensations and turn them into signals to the brain, said Ru-Rong Ji, Ph.D., a university distinguished professor of anesthesiology in the Duke School of Medicine who co-authored the study.

The new structure is resolved down to less than 3 angstroms, slightly larger than a single atom, using Duke’s new cryo-electron microscope. This level of detail can give researchers a dramatic new understanding of its functions at a molecular level. “This is something special,” Ji said. “Now we can see a lot more detail and have mechanistic insight into how it functions.”

The TRPA1 sensor is also found in flies and fish, showing it has been “evolutionally conserved to sense environmental danger,” Ji said.

This is the sensor, for example, that tells you about garlic, cinnamon and formalin, said Seok-Yong Lee, an associate professor of biochemistry in the Duke School of Medicine. “It’s a means to sense the toxic stuff to avoid damage.”

This is the latest of several TRP structures Lee’s group has resolved, including the pain and itch sensors TRPV2 and TRPV3 , and TRPM8, a sensor of cool and menthol.

What’s interesting about the wasabi sensor is how many different kinds of irritants it responds to with extraordinary speed, Lee said. The new high-resolution structure lets researchers see a binding site where chemical irritants would attach to the sensor, which provides a clue to understand its versatile but rapid irritant sensing. However, they still need to understand how irritant binding leads to opening of the channel that allows a signal to be sent. “This could help us develop new therapeutics targeting pain or itch,” Lee said.

Unlike many other TRP channels, this one signals acute inflammatory pain and neuropathic pain, as well as acute and chronic itch, depending on the type of stimulus. For example, the Ji lab recently discovered that microRNA activates TRPA1 by binding to a site different from that of wasabi to create an itch sensation.

“This channel is quite intriguing” Lee added.

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R35NS097241, R01DE17794, ZIC ES103326).

CITATION: “Structural Insights Into Electrophile Irritant Sensing by the Human TRPA1 Channel,” Yang Suo, Zilong Wang, Lejla Zubcevic, Allen Hsu, Qianru He, Mario Borgnia, Ru-Rong Ji, Seok-Yong Li. Neuron, Dec. 19, 2019. DOI: 10.1016/j.neuron.2019.11.023