Researchers at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center and University of Chicago have discovered that bacteria that usually live in the gut can accumulate in tumors and improve the effectiveness of immunotherapy in mice. The study, which will be published March 6 in the Journal of Experimental Medicine (JEM), suggests that treating cancer patients with Bifidobacteria might boost their response to CD47 immunotherapy, a wide-ranging anti-cancer treatment that is currently being evaluated in several clinical trials.

CD47 is a protein expressed on the surface of many cancer cells, and inhibiting this protein can allow the patient’s immune system to attack and destroy the tumor. Antibodies targeting CD47 are currently being tested as treatments for a wide variety of cancers in multiple clinical trials. But studies with laboratory mice have so far yielded mixed results: some mice seem to respond to anti-CD47 treatment, while others do not.

A team of researchers led by Yang-Xin Fu at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center and Ralph R. Weichselbaum, co-director of The Ludwig Center for Metastasis Research at the University of Chicago, found that the response to treatment depends on the type of bacteria living in the animals’ guts.

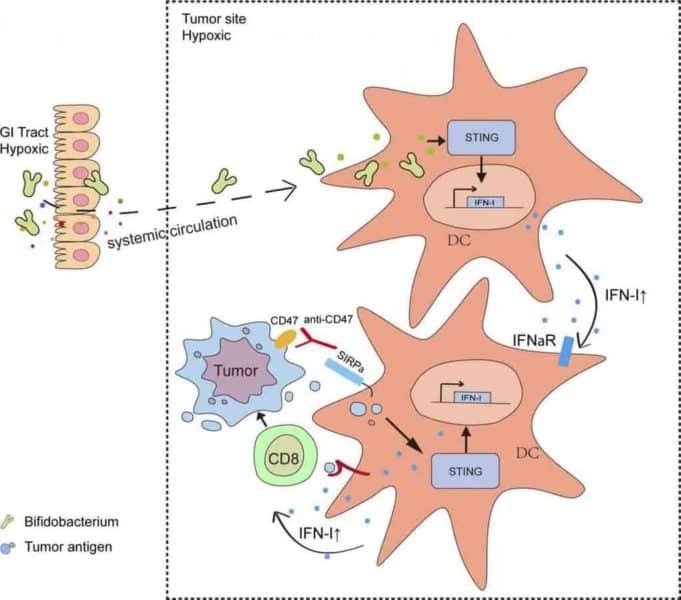

Tumor-bearing mice that normally respond to anti-CD47 treatment failed to respond if their gut bacteria were killed off by a cocktail of antibiotics. In contrast, anti-CD47 treatment became effective in mice that are usually non-responsive when these animals were supplemented with Bifidobacteria, a type of bacteria that is often found in the gastrointestinal tract of healthy mice and humans. Bifidobacteria have previously been shown to benefit patients with ulcerative colitis.

Surprisingly, however, the researchers found that Bifidobacteria do not just accumulate in the gut; they also migrate into tumors, where they appear to activate an immune signaling pathway called the stimulation of interferon genes (STING) pathway. This results in the production of further immune signaling molecules and the activation of immune cells. When combined with anti-CD47 treatment, these activated immune cells can attack and destroy the surrounding tumor.

“Our study demonstrates that a specific member of the gut microbial population enhances the anti-tumor efficacy of anti-CD47 by colonizing the tumor,” Fu says. “Administration of specific bacterial species or their engineered progenies may be a novel and effective strategy to modulate various anti-tumor immunotherapies.”

“Our results open a new avenue for clinical investigations into the effects of bacteria within tumors and may help explain why some cancer patients fail to respond to immunotherapy,” says Weichselbaum.

###

Shi et al. 2020. J. Exp. Med. https:/