Despite the traditional view that species do not exchange genes by hybridization, a new study led by Princeton ecologists Peter and Rosemary Grant show that gene flow between closely related species is more common than previously thought.

A team of scientists from Princeton University and Uppsala University detail their findings of how gene flow between two species of Darwin’s finches has affected their beak morphology in the May 4 issue of the journal Nature Ecology and Evolution.

Darwin’s finches on the Galápagos Islands are an example of a rapid adaptive radiation in which 18 species have evolved from a common ancestral species within a period of 1 to 2 million years. Some of these species have only been separated for a few hundred thousand years or less.

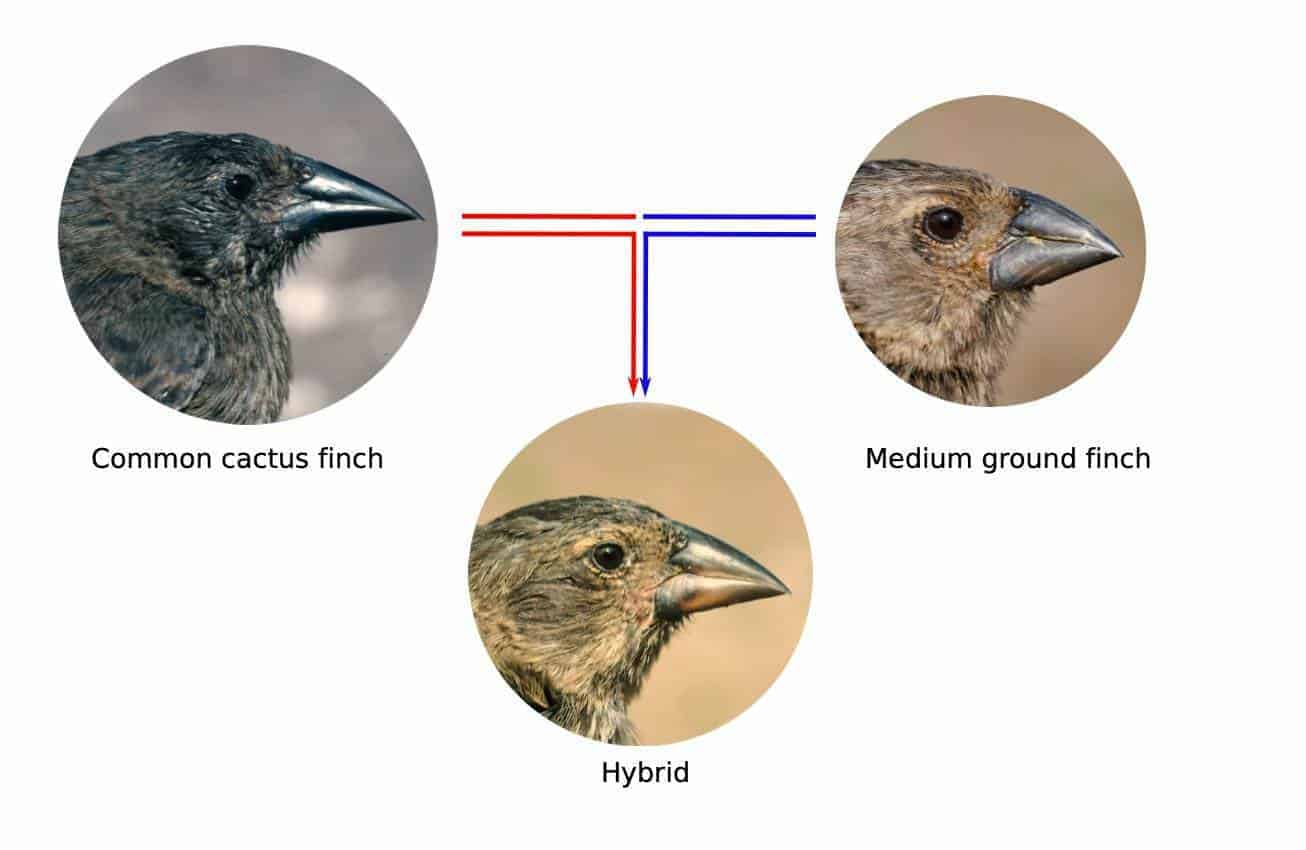

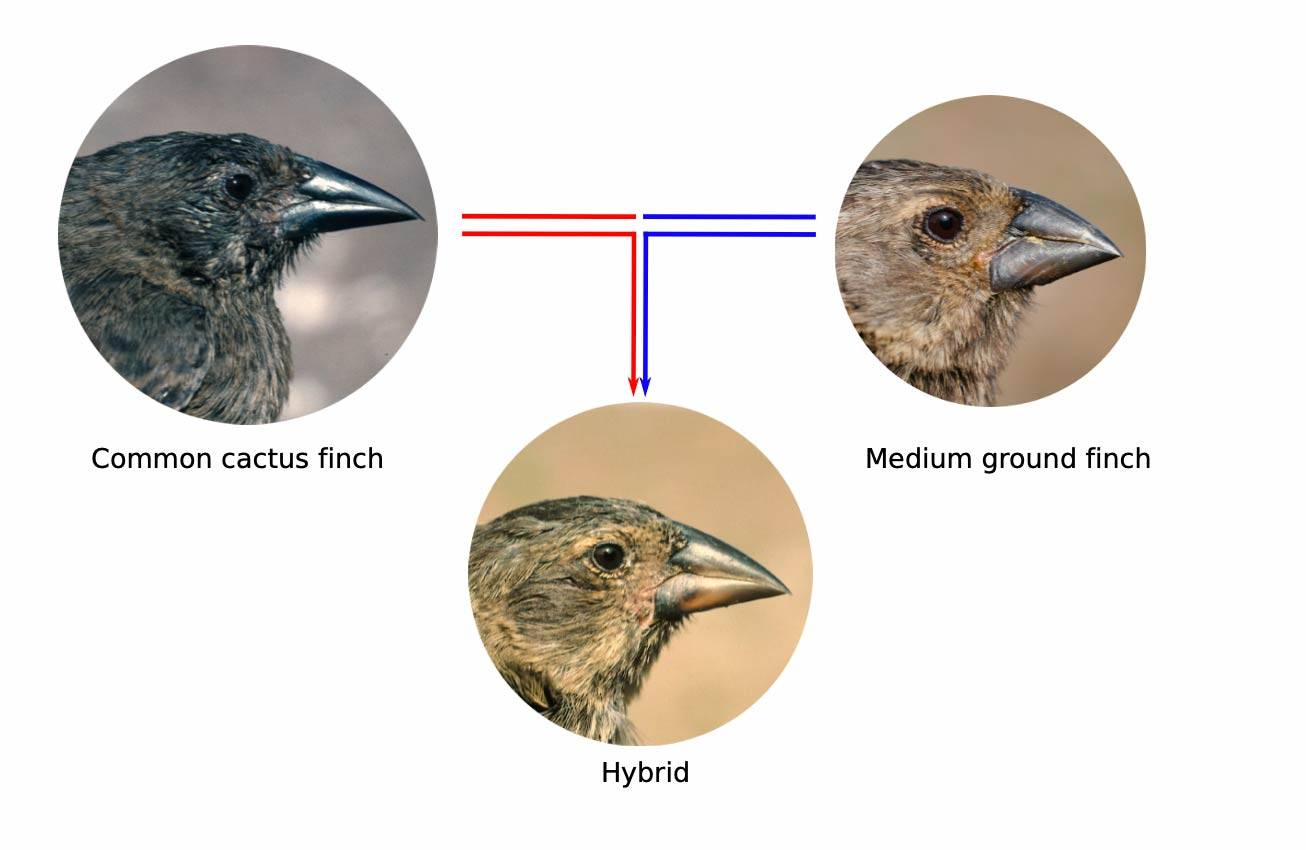

Rosemary and Peter Grant of Princeton University, co-authors of the new study, studied populations of Darwin’s finches on the small island of Daphne Major for 40 consecutive years and observed occasional hybridization between two distinct species, the common cactus finch and the medium ground finch. The cactus finch (Geospiza scandens) is slightly larger than the medium ground finch (G. fortis), has a more pointed beak and is specialized to feed on cactus. The medium ground finch has a blunter beak and is specialized to feed on seeds.

Schematic figure showing the outcome of hybridization between male cactus finches and female ground finches. Rosemary and Peter Grant have studied these birds on the small island of Daphne Major for more than 40 years. The common cactus finch has a pointed beak adapted to feed on cactus, whereas the medium ground finch has a blunt beak adapted to crush seeds. Hybrid females successfully mate with male cactus finch males, whereas the hybrid males do not successfully compete for high quality territory and mates. Because these hybrid females receive their single Z chromosome from their cactus finch father there is no gene flow on Z chromosomes between species through these hybrid females.

“Over the years, we observed occasional hybridization between these two species and noticed a convergence in beak shape,” said the husband-and-wife team, who have been research partners for decades. Peter Grant is the emeritus Class of 1877 Professor of Zoology and an emeritus professor of ecology and evolutionary biology, and Rosemary Grant is an emeritus senior research biologist.

“In particular, the beak of the common cactus finch became blunter and more similar to the beak of the medium ground finch,” continued the Grants. “We wondered whether this evolutionary change could be explained by gene flow between the two species.”

“We have now addressed this question by sequencing groups of the two species from different time periods and with different beak morphology,” said Sangeet Lamichhaney, one of the shared first authors and an associate professor at Kent State University. “We provide evidence of a substantial gene flow, in particular from the medium ground finch to the common cactus finch.”

“A surprising finding was that the observed gene flow was substantial on most autosomal chromosomes but negligible on the Z chromosome, one of the sex chromosomes,” said Fan Han, a graduate student at Uppsala University, who analysed these data as part of her Ph.D. thesis. “In birds, the sex chromosomes are ZZ in males and ZW in females, in contrast to mammals where males are XY and females are XX.”

“This interesting result is in fact in excellent agreement with our field observation from the Galápagos,” said the Grants. “We noticed that most of the hybrids had a common cactus finch father and a medium ground finch mother. Furthermore, the hybrid females successfully bred with common cactus finch males and thereby transferred genes from the medium ground finch to the common cactus finch population. In contrast, male hybrids were smaller than common cactus finch males and could not compete successfully for high-quality territories and mates.”

This mating pattern is explained by the fact that Darwin’s finches imprint on the song of their fathers, so sons sing a song similar to their father’s song and daughters prefer to mate with males that sing like their fathers. Furthermore, hybrid females receive their Z chromosome from their cactus finch father and their W chromosome from their ground finch mother. This explain why genes on the Z chromosome cannot flow from the medium ground finch to the cactus finch via these hybrid females, whereas genes in other parts of the genome can, because parents of the hybrid contribute equally.

“Our data show that the fitness of the hybrids between the two species is highly dependent on environmental conditions which affect food abundance — that is, to what extent hybrids, with their combination of gene variants from both species, can successfully compete for food and territory,” said Leif Andersson of Uppsala University and Texas A&M University.

He continued: “The long-term outcome of the ongoing hybridization between the two species will depend on environmental factors as well as competition. One scenario is that the two species will merge into a single species combining gene variants from the two species, but perhaps a more likely scenario is that they will continue to behave as two species and either continue to exchange genes occasionally or develop reproductive isolation if the hybrids at some point show reduced fitness compared with purebred progeny. The study contributes to our understanding of how biodiversity evolves.”

“Female-biased gene flow between two species of Darwin’s finches,” by Sangeet Lamichhaney, Fan Han, Matthew T. Webster, B. Rosemary Grant, Peter R. Grant and Leif Andersson, appeared in the May 4 issue of Nature Ecology & Evolution (DOI: 10.1038/s41559-020-1183-9). The research was supported by the Galápagos National Parks Service, the Charles Darwin Foundation, the National Science Foundation, the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation and the Swedish Research Council.