Editor’s note: Police reform is on the national agenda in response to the choking death of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer in late May – and many other such incidents before and since. Police Training Institute director Michael Schlosser weighed in on the current crisis. Based at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, the PTI trains dozens of police departments across the state of Illinois. Schlosser spoke with News Bureau life sciences editor Diana Yates.

What was your response to the video of a Minneapolis police officer killing George Floyd?

It was heartbreaking to witness George Floyd’s death. It was so difficult to see a human being lying on the ground, dying and begging for his life. My first thoughts were as a person, not a cop: I was angry and sad. My second reaction was as someone in the policing practice. I was thinking, “We can’t let this keep happening. This is not what policing is about.”

What do you think about the police response to protests in the wake of Floyd’s death?

I was horrified to see some officers using violence on peaceful protesters, to see an elderly man in his 70s get knocked to the ground by police, lie there on the ground, bleeding from the head, and officers walking by. There has to be change – and now.

Many officers showed restraint during the protests, even with protesters yelling and cursing at them. Those officers handled the situations professionally. But the focus now should be on the horrific police tactics. As someone who runs a police academy, it is my job to continue being proactive for police reform.

What do you think is the cause of the current crisis in policing?

First, racism is an everyday part of American society, and policing and the criminal justice system are included in that. Watching the many recent incidents and listening to communities around the country crying out for something better, I can see that we need change in policing practice and police culture.

This isn’t a new realization for me. My team and I have been studying and implementing police-reform programs since early 2014. Our programs are designed to give police officers a better understanding of their own implicit biases and expose them to some of the issues that will be important when they interact with diverse communities. The classes began at PTI before the death of Michael Brown at the hands of police in Ferguson, Missouri. So far, hundreds of police recruits have taken part in these programs.

What should police reform entail?

We need to hire the right people, hold them accountable and get rid of those who violate the ethical code expected of police officers. We need to make sure that officers who violate this code don’t have the opportunity to be hired by any other law enforcement agency.

So much training is needed, and it must be continuous throughout a police officer’s career. Officers need to learn how to de-escalate situations and to be aware of their own implicit biases. They need to take the time to develop cultural competency with regard to the communities they serve. They ought to learn about historical issues involving the intersection of police and race. They also should be thoroughly invested in community policing.

Some communities are talking about defunding, abolishing or redesigning their law enforcement systems. What’s your response to those ideas?

Abolishing police is nonsensical, and I don’t think that is what our citizens really want. I can understand their frustrations and why they might call for this type of narrative. But who will you call when you have an active shooter, when someone is breaking into your house, when your spouse or partner is battering you, or when you are a victim of any crime that needs to be investigated, like criminal sexual assault or elder abuse?

I don’t want to see funds taken away from police agencies. But I do want to see a lot more funding going to organizations and professionals that can take on some of the roles police officers have had to do every day for years. Professional social workers, counselors, psychologists and medical personnel have the expertise and can follow up on many of the issues our citizens are experiencing.

That said, we train officers to interact with people who are in a crisis; have mental health issues or developmental disabilities; or are suffering from anxiety, depression, financial difficulty or substance-abuse issues. Police can provide contacts for professional help and are trained to offer some limited counseling. But they cannot offer the same service as a professional could on the spot.

Police agencies cannot afford to lose funds. Officers need continued training in many areas. They also need to have time in their day for positive community engagement. Officers need to get out of their squad cars and interact with citizens when it is not a call for service, a domestic dispute or a traffic stop. Casual interactions build trust and understanding. But if departments are underfunded and work with minimum staffing, they can’t get out into the neighborhoods, visit youth centers or attend community events.

Officers in understaffed police departments spend much of their time handling calls and writing reports, and this can lead to burnout. Cutting their funding further would not be helpful to the future of policing.

What initiatives are you taking at the Police Training Institute to promote police reform?

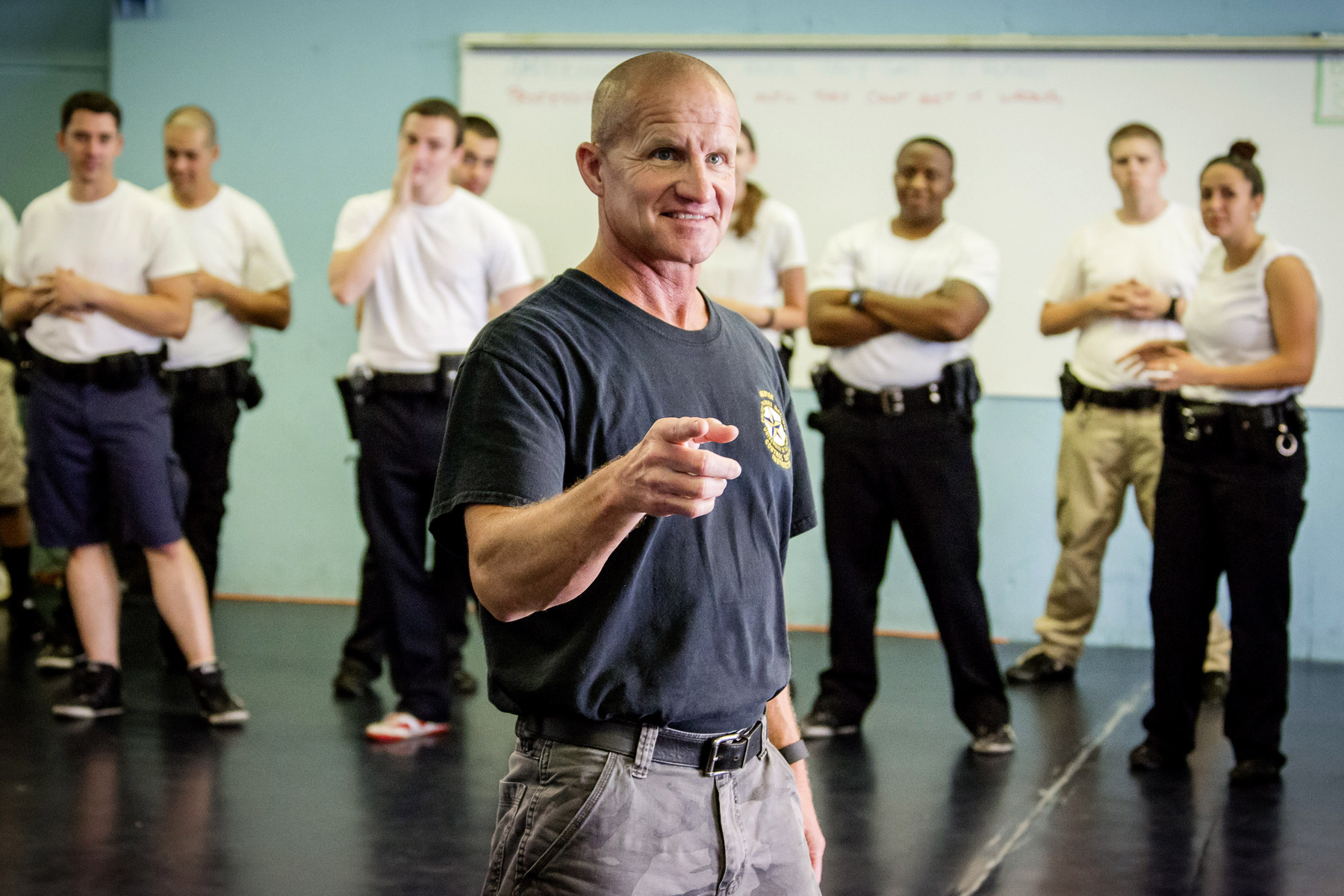

We do not use a military approach in our academy. We train recruit officers using the adult-learning model, which involves scenario-based training. Our trainees learn nonescalation and de-escalation techniques as well as community policing by engaging in scenarios that they are likely to encounter in their life as a police officer.

We also offer courses that are not mandated by the state. These include Policing in a Multiracial Society, LGBTQ Ally Training, and Wrongful Conviction Awareness and Prevention. These programs give our recruit officers an opportunity to listen to the voices of those who are not always heard, to help create respect and empathy.

We work with faculty members and researchers at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and with the leaders of the Illinois Innocence Project at the U. of I. at Springfield to build and improve our educational programs.

The state mandates 40 hours of scenario-based training, but we offer more than twice that amount. The majority of these exercises involve nonescalation and de-escalation training.

We also know that it is essential for recruit officers to be proficient and confident in their control and arrest tactics. Thirty-two hours is required by the state, but we offer 53 hours in this type of training. I have always thought the more an officer is confident in these tactics, the more likely they are to spend more time talking and de-escalating. Conversely, officers who are not well-trained and confident in their physical tactics are more likely to react based on fear or biases, rather than responding to the behavior they are observing. This makes them more likely to resort to physical confrontations at an earlier stage of an interaction.

Will continuing education or community partnerships solve this problem?

Continuing education for police officers will make a difference, but only if it is quality training. And, we can only get to where we need to be with community partnerships. Departments should not have one officer labeled as “community policing officer.” Rather, every officer on the department, from patrol to the chief or sheriff, must be community policing officers.