Despite frequently shouted concerns by both Democrats and Republicans, voting by mail doesn’t lend either political party an advantage on Election Day, though it might account for a slight uptick in overall voter participation, according to research led by UCLA professor of political science Daniel Thompson.

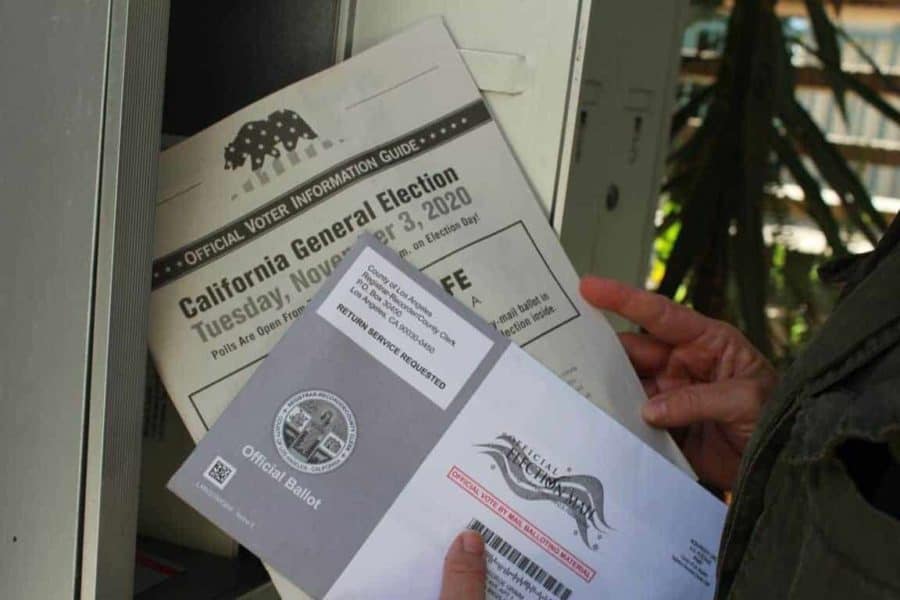

Researchers tracked voting behavior from 1996 to 2018 in California, Utah and Washington state. These states have adopted universal vote-by-mail — the practice of mailing every registered voter a ballot with a return envelope — and have rolled out the system on a staggered basis by county over several election cycles.

Analysts compared voting data from those counties within each state that had switched to universal vote-by-mail with those that hadn’t and found no statistically significant increase in the amount of votes Democratic candidates gained over Republicans, or vice versa. They did track an average 2% increase in voter participation in counties that had adopted voting by mail.

The study, which was published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences this summer, was Thompson’s last project as a Stanford doctoral candidate before he joined the UCLA faculty in July. Thompson’s co-authors were fellow Stanford graduate students Jennifer Wu and Jesse Yoder and Stanford professor of political science Andrew Hall.

“The big caveat is we were looking at normal times, not coronavirus times,” Thompson said. “It remains to be seen how much of an impact universal vote-by-mail has during the pandemic — we don’t know how well it will be conducted or who would fail to vote if they had to vote in person.”

Still, the study results imply that the partisan outcomes of vote-by-mail elections closely resemble in-person elections, both in voter turnout and electoral outcome, at least in normal times.

Researchers initially considered comparing election results and turnout between states with and without universal vote-by-mail policies but found that certain systematic and partisan differences in vote-by-mail states could have skewed the results. Only six states in total have adopted the practice: the three studied and Colorado, Hawaii and Nevada.

“It’s very clear, even just looking at a map — Western states are places that have been much more open to the adoption of universal vote-by-mail,” Thompson said. “It’s not necessarily about obvious or presumed ‘left’ or ‘right’ places; it seems to be more about geography and maybe even culture around going to polling places on Election Day.”

The team tackled that challenge by analyzing voting results by county within each state and comparing election years when vote-by-mail was offered and when it was not. They focused on voting results for candidates for statewide offices, which were standard across counties.

The researchers have been sharing their findings with election officials and policymakers as the debate over the merits of vote-by-mail continues to reach a fever pitch in the media and among political partisans.

“We know there is a lot of consideration and a lot of challenges when it comes to implementing universal vote-by-mail, including the expense of it,” Thompson said. “Our goal is to be an input to that very deliberative process and inject some more facts and figures into the discussion.”