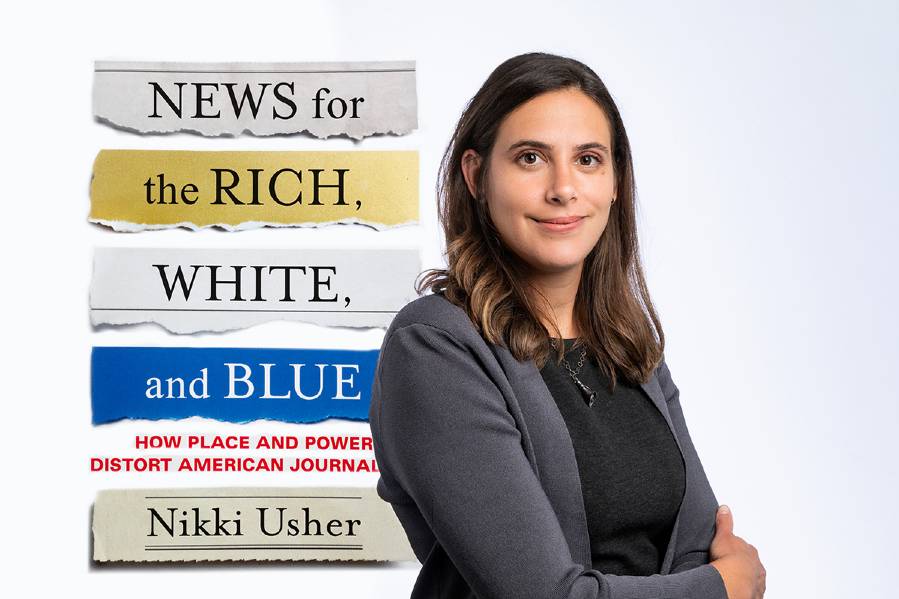

A new book by University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign journalism professor Nikki Usher examines the market failure of local newspapers in the context of larger U.S. problems such as rising social inequality, geographic polarization and political discord. In “News for the Rich, White, and Blue: How Place and Power Distort American Journalism,” Usher posits that newspapers are becoming more focused on serving wealthy, white and politically liberal news consumers.

In the wake of the many local newspaper collapses, the American public is left wondering how this new reality fits into America’s foundational idea of an informed and representative democracy. Usher wrote that newspapers have not served American democracy well in this area for a long time.

“It is a well-accepted premise that local journalism is inherently good for democracy, and that it is something that we absolutely need for democratic life to function and flourish,” Usher said in an interview. “But, as newspapers continue to rely on subscription revenue, they need to hold the interest of those willing and able to pay for news. This leads to journalism that perpetuates an elite democracy, where news is about elites for elites.”

This problem is nothing new to journalism, Usher said. Mainstream journalism perpetuates the status quo and newsrooms remain stubbornly white and increasingly off limits to those without a financial safety net, despite efforts made in the past to correct the issue. These shortcomings within newsrooms are compounded by the financial crisis facing newspapers. “To survive, some newspaper executives concede that it is wealthy white people who continue to pay for news,” she said.

One of those newsrooms most likely to survive is The New York Times, a site of Usher’s previous research in her book “Making News at the New York Times.” Ten years after her initial research, Usher returned to the newspaper and found that the newsroom’s survival strategy now explicitly focuses on reaching an elite, global audience, even as newsrooms leaders are aware that they are out of touch with nonurban, noncoastal America.

While philanthropy, nonprofit news organizations and public media are often touted as better business models for news organizations, Usher reminds the reader that philanthropists often have pet causes, and nonprofit and public media still rely on those who can pay for news.

“In the book, I illustrate this with data to show that news philanthropy overwhelmingly goes from foundations in blue places to journalism in big blue cities, regardless of how much or how little news provision is available,” Usher said.

But that does not mean that Americans should let go of hope for good local journalism, Usher said, because it is a powerful concept. She offers a variety of possible solutions.

“One solution may be the return to local partisan reporting,” she said. “Being open and honest about partisanship is really important, particularly in local communities. In the American news market, the Republican Party is funding some local news organizations, but the Democratic Party has done little to think about how they’re going to respond. Going back to the party-subsidized press may not be such a bad idea. After all, partisan media sells.”

Usher also offers local news innovations such as looking to local institutions and organizations already in place for help.

“There are many things that newspapers do that community organizations, institutions and civic groups already do,” she said. “For example, the public health department in my county has been responsible for producing maps and charts of COVID-19 case numbers. We should look more closely into the value of offloading basic responsibilities of ordinary information gathering to these types of groups.”

Usher also holds affiliate appointments in communication and political science at the U. of I. She is the author of “Interactive Journalism: Hackers, Data, and Code” and a senior fellow at the Open Markets Institute’s Center for Journalism and Liberty, a Washington, D.C.-based think tank. Editor’s notes: To reach Nikki Usher, call 213-220-7824; email [email protected]; Twitter handle @nikkiusher.