A drug used to treat epilepsy patients could help prevent stroke in people whose arteries show signs of atherosclerosis – furring of the arteries – scientists will tell audiences at the Cambridge Festival this week.

One of the major causes of stroke, particularly among older individuals and people who have high blood pressure, high cholesterol or smoke, is atherosclerosis, hardening and narrowing of the vessels that carry blood from the heart to the brain. It is caused by the build-up of abnormal material called plaques – collections of fat, cholesterol, calcium and other substances circulating in the blood.

While once over it was thought that it was the narrowing of the arteries that led to stroke, scientists now think it is due to inflammation. The body’s immune system causes damage to the plaques, causing blood clots to form on the surface of the wall, which can break away and travel to the heart or brain, where they can lead to potentially serious problems.

“Treatments for carotid atherosclerosis haven’t really progressed in the last 30 years or so: it’s generally surgery or aspirin. But for frailer individuals, surgery may not be an option, so we really need to find better drugs to help manage their condition.”

Dr Nick Evans, Department of Clinical Neurosciences, University of Cambridge

Dr Evans and colleagues are particularly interested in repurposing existing drugs. These drugs will have already been through safety trials, removing one of the major hurdles facing any new medication.

One of the drugs that they are interested in is sodium valproate, a drug that has been used for decades to treat individuals with epilepsy. Work by Evans’s colleague Professor Hugh Markus showed that people who are on this medication are less likely to experience stroke than the general population, and also less likely than epilepsy patients taking other antiepileptic drugs.

When the team studied the plaques that build up in atherosclerosis, they found higher than anticipated levels of an enzyme known as HDAC9, which helps control the activity of other genes. Sodium valproate appears to inhibit the activity of HDAC9.

“Drugs that inhibit the activity of a number of HDAC enzymes are already being used to treat cancers such as gastrointestinal cancers and leukaemia,” says Dr Evans, “but because they are – with good reason – targeting a number of these enzymes at the same time, they have strong side effects, so wouldn’t be suitable to atherosclerosis. But a drug that targets just the key enzyme would work with far fewer side effects – and that’s what we think we’ve found with sodium valproate.”

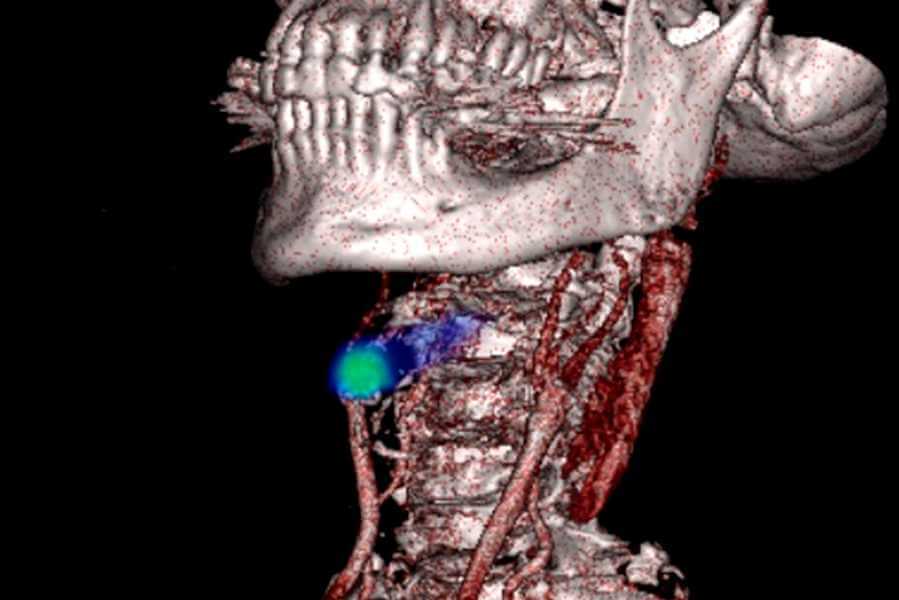

The team have begun recruiting patients to a small trial at Addenbrooke’s Hospital, part of Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust. Patients on the trial will be randomised, with some receiving sodium valproate in addition to their normal medication over a two year period. They will undergo MRI scans to look at the degree of narrowing of their arteries and PET scans to measure inflammation. If the drug appears to be beneficial, the team will move to a phase 3 clinical trial – a much larger scale trial.

Recruitment is underway for patients in the East of England who have had a stroke within the previous six months.

To find out more about the trial, visit the Stroke Research Group website.