The 1972 book The Limits to Growth shared a somber message for humanity: the Earth’s resources are finite and probably cannot support current rates of economic and population growth to the end of the 21st century, even with advanced technology.

Although disparaged by economists at the time, it turns out that, 50 years later, the message still deserves our attention.

University of California San Diego Professor of Physics Thomas Murphy believes that although no one can say with absolute certainty that the planet will reach an unavertable crisis by the end of this century, our current trajectory is unable to continue much longer. His assessment appears in a comment paper recently published by Nature Physics.

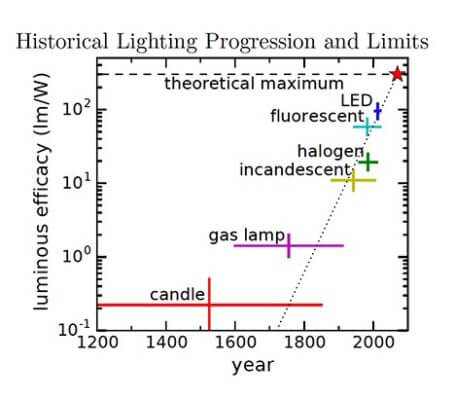

Trained as an astrophysicist, Murphy became interested in planetary limits after teaching a class on energy and the environment. Students explored the physics of energy, how to calculate energy demand and resources and the resulting environmental impacts. Murphy realized the issues of resource and energy consumption were more severe than many assumed.

“This is something not enough people are paying attention to,” Murphy stated. “What does life look like after resource depletion? What actions can we take now to mitigate the worst outcomes—and how do we get people to take this seriously?”

The Earth has finite resources—this is clear when thinking of fossils fuels, mined minerals or land, but it can be difficult to imagine a time when humankind will have to adjust its way of living to accommodate for these limits.

In the past, the Earth was able to accommodate our increasing resource demands,” said Murphy, who wrote a book exploring the topic called Energy and Human Ambitions on a Finite Planet. “But remember, the Earth has never hosted 8 billion humans before, all of us pursuing increased consumption demands. We cannot base projections for future resources on the past. This is uncharted territory.”

To illustrate this point, Murphy calculated future energy consumption using our historical growth rate of a factor of ten each century. If humans currently consume 18 TW (terrawatts) of energy globally, by 2100 that number jumps to 100 TW, by 2200 it’s 1,000 TW and so on. In 400 years, we would exceed the total solar power incident on Earth and in 1,300 years, the entire output of the Sun in all directions.

Using the same growth rate to extrapolate future levels of waste heat (the end product of all our energy use, ultimately radiated to space) also provides a grim outlook: the amount of waste heat produced would accelerate and cause terrestrial temperatures to soar. Just beyond 400 years the Earth’s surface would reach the boiling point of water.

Murphy clarifies that this extrapolation of energy consumption and waste heat is not realistic and not a prediction. It was created to show that our historical unimpeded growth cannot continue indefinitely into the future. In fact, if the progression shows anything, it’s that the period of unrestrained energy consumption on Earth will be relatively short-lived compared to the longevity of civilization.

Even the most optimistic of economists will concede there is a limit to the Earth’s physical resources, but many insist this won’t impact economic growth because money will be “decoupled” from physical resources, thus able to grow without being constrained by the depletion of fossil fuels or minerals.

“Some might say money doesn’t have to obey the laws of physics or that we can sustain economic growth through innovation,” Murphy states. “But those things are not immune to limits. Even if you think about life in the virtual realm—that requires physical resources too, to build and run those computers. We’re seeing that for bitcoin mining and the massive amounts of energy it consumes.”

It is true, Murphy concedes, that many economic activities do not require intense use of physical resources—work in the legal and financial sectors, for instance, primarily use lighting, heating and computers but are not fabricating concrete and steel. While it may be easy to assume the proportion of decoupled activities will continue to increase while resource demands continue to decrease indefinitely, at some point the demand for physical resources can shrink no further. As Murphy notes, humans will always need food.

“We don’t see the economic growth we’re currently experiencing for what it is: a phase,” stated Murphy. “And one reason we don’t see it is because we don’t want to and have never had to. Continued growth spares us from having to address the issue of reallocating present resources more equitably.”

He notes that the perceived benefits of economic growth are a double-edged sword. As the economy grows, people may be lifted out of poverty, and given better access to water, food and health care. Their populations grow and, as the standard of living rises, the higher resource demands overtax the planet’s capacity and threaten to remove those same benefits.

Murphy says the real solution is long-term planning and requires a fundamental shift in how we think of ourselves as a species. “We need to change our relationship with the planet. We need the humility to accept that we do not own the Earth. But how do you convince somebody of something that’s never happened before, lies in the future and requires sacrifice? I hope that we can plant some seeds soon that will lead to wiser decisions down the road.”