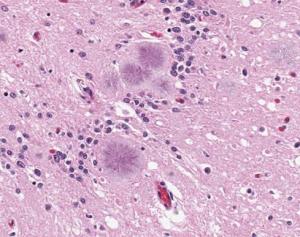

The brains of people with Down syndrome develop the same neurodegenerative tangles and plaques associated with Alzheimer’s disease and frequently demonstrate signs of the neurodegenerative disorder in their forties or fifties. A new study from researchers at UC San Francisco shows that these tangles and plaques are driven by the same amyloid beta (Aß) and tau prions that they showed are behind Alzheimer’s disease in 2019.

Prions begin as normal proteins that become misshapen and self-propagate. They spread through tissue like an infection by forcing normal proteins to adopt the same misfolded shape. In both Alzheimer’s and Down syndrome, as Aß and tau prions accumulate in the brain, they cause neurological dysfunction that often manifests as dementia.

Tau tangles and Aß plaques are evident in most people with Down syndrome by age 40, according to the National Institute on Aging, with at least 50% of this population developing Alzheimer’s as they age.

The new study, published Nov. 7, 2022, in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, highlights how a better understanding of Down syndrome can lead to new insights about Alzheimer’s, as well.

“Here you have two diseases—Down syndrome and Alzheimer’s disease—that have entirely different causes, and yet we see the same disease biology. It’s really surprising,” said Stanley Prusiner, MD, the study’s senior author, who was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1997 for his discovery of prions.

Down syndrome is the most common neurodegenerative disease among younger people in the United States, while Alzheimer’s is the most common among adults.

Down syndrome occurs because of an extra copy of chromosome 21. Among the many genes on that chromosome is one called APP, which codes for one of the major components of amyloid beta. With an extra copy of the gene, people with Down syndrome produce excess APP, which may explain why they develop amyloid plaques early in life.

Young Brains Give a Clearer Picture

It’s been known for some time that Aß plaques and tau tangles are present in both Down syndrome and Alzheimer’s. Having shown earlier that these neurodegenerative features are provoked by prions in Alzheimer’s, the researchers wanted to know whether the same aberrant proteins were present in the brains of people with Down syndrome.

While there have been extensive studies of these plaques and tangles in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s disease, it can be challenging to discern which changes in the brain are from old age and which are from prion activity, said Prusiner, director of the UCSF Institute for Neurodegenerative Diseases, part of the Weill Institute for Neurosciences.

“Because we see the same plaques-and-tangles pathology at a much younger age in people with Down syndrome, studying their brains allows us to get a better picture of the early process of disease formation, before the brain has become complicated by all the changes that go on during aging,” he said. “And ideally, you want therapies that address these early stages.”

Employing a variation on the novel assay they used in the Alzheimer’s study, the team looked at donated tissue samples from deceased people with Down syndrome, which they obtained from biobanks around the world. Of the 28 samples from donors aged 19 to 65 years old, the researchers were able to isolate measurable amounts of both Aß and tau prions in almost all of them.

New Insights Could Lead to Prevention

The results confirm not only that prions are involved in the neurodegeneration seen in Down syndrome, but that Aß drives the formation of tau tangles as well as amyloid plaques, a relationship that has been suspected but not proven.

“The field has long tried to understand what the intersection is between these two pathologies,” said lead author Carlo Condello, PhD, also a member of the UCSF Institute for Neurodegenerative Diseases. “The Down syndrome case corroborates the idea; now you have this extra chromosome that’s driving the Aß, and there’s no tau gene on the chromosome. So, it’s truly by increasing the expression of Aß that you kick off production of the tau.”

That insight and others gleaned from studying the brains of people with Down syndrome will lead to a much better picture of how prions begin to form in the first place, said Condello.

Whether the Down syndrome brain tissue will prove to be the ultimate model for developing treatments for Alzheimer’s remains to be seen, the researchers said. While the two disorders share many similarities in their prion pathobiology, there are some differences that may be limiting.

Still, the researchers said, studying the plaques and tangles in Down syndrome is a promising route to identifying the specific prions that arise at the very earliest stages of the disease process. That insight could open new vistas on not only treating but perhaps even fending off Alzheimer’s disease.

“If we can understand how this neurodegeneration begins, we are one big step closer to being able to intervene at a meaningful point and actually prevent these large brain lesions from forming,” Condello said.

Authors: Additional UCSF authors on the study include Alison Maxwell, Department of Pharmaceutical Chemistry, and Erika Castillo, Atsushi Aoyagi, William Seeley, of the UCSF Weill Institute for Neurosciences. For other authors, please see the study.

Funding: This work was supported by NIH grants P01AG002132, P30AG066519, AG023501, and AG019724, and DHA grants HU311661-040066323 and HU0001-19-2-000 along with other institutes and and philanthropy. For a complete list, please see the study.