In the post-World War II period, Hong Kong became a battleground for the competing ideologies of China, Taiwan and the U.S. in a cultural cold war.

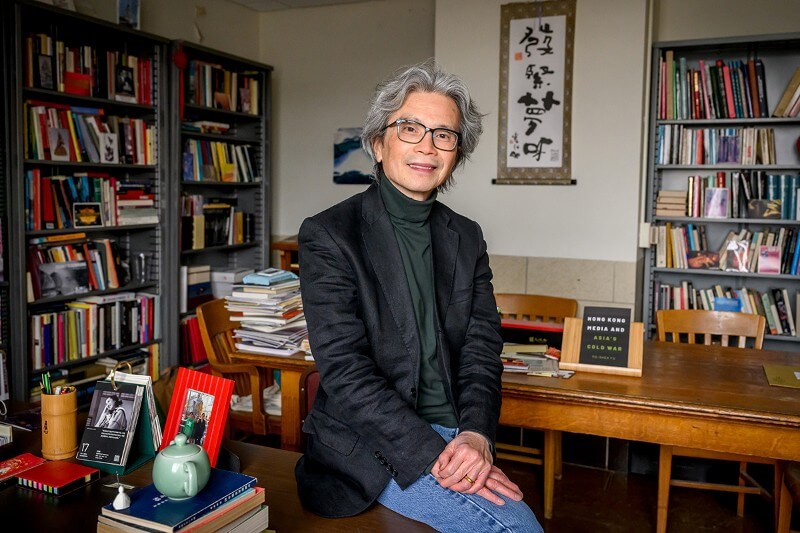

University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign history professor Po-Shek Fu described how the propaganda and psychological warfare intertwined with the local historical experiences and cultural formation of Hong Kong. His new book, “Hong Kong Media and Asia’s Cold War,” was published by Oxford University Press.

The conflict between the communists who came to power in mainland China in 1949 and the nationalists who were driven into exile in Taiwan coincided with the Cold War between the U.S. and the former Soviet Union and their proxies. But the important role of Hong Kong in the Asian cold war has been neglected in research, said Fu, who studies U.S.-China cultural relations, Chinese language cinema, and war and cultural interactions. He said his book is the first systemic study of Hong Kong’s role in the global Cold War.

Following the communist revolution in China, many Chinese intellectuals, journalists and artists fled to Hong Kong, then a British colony that proclaimed neutrality in Cold War politics. With the large population of highly educated exiles – many of whom were involved in the cultural cold war – Hong Kong’s media, and particularly its film industry and print journalism, developed rapidly. By the 1970s, Hong Kong was the third-largest producer of films in the world, behind Hollywood and Bollywood. It produced a “golden age” of Mandarin cinema and popular culture, Fu said.

Hong Kong’s media outlets were aligned with particular ideological factions, with the aim of gaining the support of ethnic Chinese living throughout Southeast Asia and around the world. The communist government in China established film studios in the British colony that initially created movies with a patriotic fervor and anti-imperialist viewpoint, urging its audiences to return to the socialist utopia of China. To avoid direct antagonism with the colonial authority, they later moved to wholesome, family-oriented content with moral messages “of guiding people to do good,” Fu said.

The pro-Taiwan “free China” studios used covert political messages that were pro-freedom or pro-Taiwan. In its contest to be China’s only legitimate government, Taiwan didn’t control film production directly but instead weaponized its market through regulation, allowing only pro-Taiwan films to be distributed, Fu said. The U.S. sought to contain Chinese influence in Southeast Asia. For example, the Asia Foundation, a nonprofit organization funded by the CIA, intervened by supporting film studios and print publications that featured strong Cold War messages from the U.S. viewpoint.

To maintain its authority, the Hong Kong government tried to depoliticize the media, including through censorship, and prioritized a profitable business environment, apolitical entertainment and global expansion, Fu wrote. One of the key legacies of the Cold War in Hong Kong is that the rivalry and propaganda war between China, Taiwan and the U.S. “reinforced and intensified the efforts of the colonial authority – and its big business allies – to tighten its political grip and to depoliticize cultural production, championing the laissez faire policy of prosperity and stability,” he wrote.

The conflict in the media found expression in particular in the way the two camps – pro-communist and “free world” – projected their contested versions of China’s modernity. For example, communist movie studios made the first color films that were distributed through Hong Kong to overseas Chinese communities to promote China’s technological expertise, Fu said.

The book also discussed the impact of the global Cold War on Hong Kong. The British colony’s place as a strategic crossroads in Asia’s cold war contributed to Hong Kong’s modernization and significantly shaped its cultural changes, Fu wrote.

“The battles for hearts and minds fostered a politicized and antagonistic atmosphere, but it also drove rapid expansion and industrial transformation of the media ecosystem. They accelerated movement of money, new technique and technology, new management and professional standards, and cultural innovation such as new-styled opera and martial arts films, and spurred market expansion and regionwide cultural exchanges and co-production,” he wrote.

Fu said he wanted to show the agency of local actors in Hong Kong as they were caught in the middle of the Cold War and Taiwan Strait conflicts, and their influence on global politics, not just the effects of the conflicts between superpowers.

He also wrote about the rise of a new generation that grew up in postwar Hong Kong and, unlike their parents, saw it as their home, not mainland China. The global geopolitics gradually shifted in the region and Hong Kong became industrialized and wealthy. Its younger generation was well-educated and often attended college in the West. They challenged the Cold War network of cultural production, were socially conscious and increasingly frustrated by with the city’s colonial injustice, and yet many were ambivalent toward their homeland of China. As Hong Kong approached its handover to China In 1997, filmmakers, artists and writers began to search in earnest for a new Hong Kong identity, Fu said.

“In recent years, as post-colonial Hong Kong was once again caught up, in a very different way, in a new cold war between China and the U.S., the struggle to construct a local identity has become dangerously politicized and polarized in a way that reminds us of Hong Kong’s long history of cultural cold war,” he said.