A new study of more than 200 women by investigators from Brigham and Women’s Hospital and the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health details links between specific gut bacteria and positive emotions like happiness and hopefulness. The results were published in Psychological Medicine.

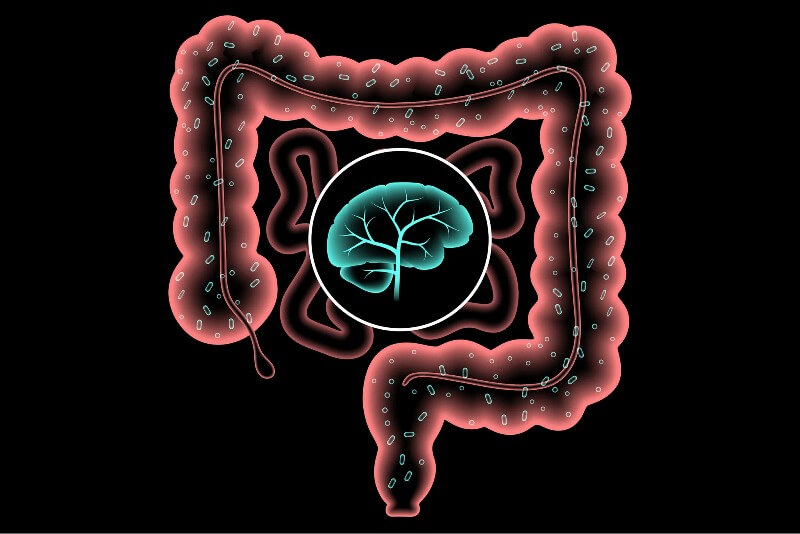

According to past research, the brain communicates with the gastrointestinal tract through the gut-brain axis. One theory is that the gut microbiome plays a starring role in the axis, linking physical and emotional health.

“Many studies have shown that disturbance in the gut microbiome can affect the gut-brain axis and lead to various health problems, including anxiety, depression, and even neurological disorders,” said co-corresponding author Yang-Yu Liu, an associate scientist at the Brigham and an associate professor at Harvard Medical School.

“This interaction likely flows both ways — the brain can impact the gut, and the gut can impact the brain,” said first author Shanlin Ke, a postdoctoral researcher in Liu’s lab. “The emotions that we have and how we manage them could affect the gut microbiome, and the microbiome may also influence how we feel.”

The gut-brain axis might affect physical health, as well. Past research has shown that positive emotions and healthy emotional regulation are linked to greater longevity. In contrast, negative emotions are linked to higher rates of cardiovascular disease and mortality from all causes, according to Laura Kubzansky, a professor in the Chan School’s Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences and co-corresponding author of the new research.

The new study included women from a mind-body sub-study of the Nurses’ Health Study II. These middle-aged, mostly white women filled out a survey that asked about their feelings in the last 30 days, asking them to report positive (feeling happy or hopeful about the future) or negative (sad, afraid, worried, restless, hopeless, depressed, or lonely) emotions. The survey also assessed how they handled their emotions. The two options were reframing the situation to see it in a more positive light or suppressing negative emotions.

Three months after answering the survey, the women provided stool samples, which were analyzed using metagenomic sequencing. The team compared the results from the microbial analysis to the survey responses about emotions, looking for connections.

“Some of the species that popped up in the analysis were previously linked with poor health outcomes, including schizophrenia and cardiovascular diseases,” said co-first author Anne-Josee Guimond, a postdoctoral researcher in Kubzansky’s lab. “These links between emotion regulation and the gut microbiome could affect physical health outcomes and explain how emotions influence health.”

The analysis found that people who suppressed their emotions had a less diverse gut microbiome. The investigators also found that people who reported happier feelings had lower levels of Firmicutes bacterium CAG 94 and Ruminococcaceae bacterium D16. On the other hand, people who had more negative emotions had more of these bacteria.

“I was intrigued that positive and negative emotions often had consistently similar findings in opposite directions,” Kubzansky said. “This is what you would expect, but kind of amazing to me that we saw it.”

The researchers also examined what the microbes in the gut were doing on a functional pathway level, looking for links between changes in the capacity of this activity and specific emotional states and emotion regulation methods. They found that negative emotions were linked to lowered capacity activity in multiple metabolism-related actions.

The researchers hope to repeat the study with more diverse populations, a more extensive emotional survey, and longitudinal data. A more specific analysis of the microbial strains might also help develop microbiome-based therapeutics like probiotics to improve emotions and well-being.