Researchers at Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine have developed a first-of-its-kind, orally administered drug to disrupt prostate cancer cells’ metabolism and deliver the chemotherapy agent cisplatin directly into treatment-resistant prostate cancer cells.

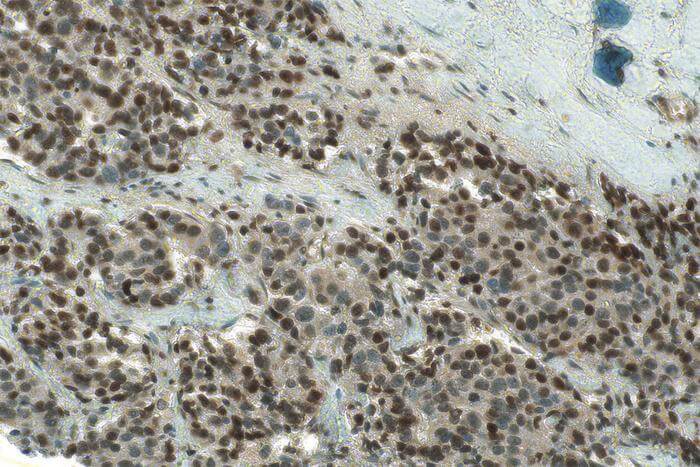

They validated their targets in human prostate cancer biopsies, tested the new approach in human cancer cells and a mouse model of prostate cancer, showed that it is safe and effective in shrinking treatment-resistant cancers, and published results as the cover article in ACS Central Science, an American Chemical Society journal.

Although cisplatin is one of the most potent chemotherapy drugs in use against a variety of cancers, it has not been effective in treating prostate cancer. The Sylvester researchers’ compound – Platin-L – works in two ways, breaking down a process that malignant prostate cancer cells use to fuel their growth, and delivering cisplatin directly into treatment-resistant cancer cells.

“We believe Platin-L can circumvent these resistance mechanisms,” said Shanta Dhar, Ph.D., assistant director of Technology and Innovation at Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center, an associate professor of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, a researcher, co-leader of Engineering Cancer Cures, and the study’s senior author.

Normal prostate gland cells use a biochemical reaction to turn glucose into energy, and in most types of cancers, this same process – glycolysis – supports proliferation, growth, and metastasis. But prostate cancer and some other cancers are different. As they advance, they switch from glycolysis and alter enzymes that enable them to derive energy through a process called fatty acid oxidation (FAO). The tumor cells use fat instead of sugar for energy.

Platin-L targets a key component of this process: CPT1A, a protein in mitochondria, which are organelles within cells that generate energy.

“We know that when this compound binds to CPT1A, it inhibits fat metabolism and is eventually transported to the mitochondria, where it damages mitochondrial DNA and helps overcome resistance,” Dhar said. “We are also making prostate cancer cells choose a less favorable metabolic pathway, which is insufficient to their needs, making it difficult for them to survive.”

In the study, researchers treated both patient prostate tumor samples and cisplatin-resistant animal models. Platin-L, which is called a “prodrug” because it only turns into an active drug when metabolized in the body, destroyed the cancer cells by robbing them of their energy source and dismantling both mitochondrial and nuclear DNA.

Platin-L was encapsulated in nanoparticles targeting a protein called prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA), which is highly expressed in prostate tumors. This design allows the drug to be taken orally, and because its effects are largely contained within prostate cancer cells, side effects in other parts of the body are limited. In mouse models, tumors in animals treated with Platin-L shrank – unlike those untreated or treated with cisplatin alone – and the treated mice had steady body weight, increased survival rates, and little evidence of the peripheral neuropathy that often results from cisplatin treatment.

The researchers believe other nanoparticles could be engineered to target other cancers; in fact, the nanoparticles repurposed for prostate cancer in this study were initially developed in response to South Florida’s Zika virus outbreak in 2016.

“We made a dual-targeted nanoparticle,” Dhar said. “The first targeting is needed to get it through the gut barrier, and the second targeting takes it to the prostate. The beauty is, now we can deliver a cisplatin-based chemotherapeutic orally, which is usually never done. And by targeting the prostate, we can reduce kidney and liver toxicity and the risk of peripheral neuropathy.”

Dhar and colleagues say the results of this preclinical work appear promising for future clinical trials and development.

“The impact of this current targeted metabolic modulation of the tumor microenvironment for advanced prostate cancer extends beyond this cancer type,” the authors wrote. “The reported mechanistic investigations will allow us to find the clues to make this platform more general to be used for cancers where these cellular pathways can be altered.”

Funding: This work was supported, in whole or in part, by the Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center and a Bankhead-Coley Grant (8BC10) from the Florida Department of Health (to S.D.). We also acknowledge National Cancer Institute-funded Sylvester Cancer Center support grant 1P30CA240139.