A Duke University team has discovered that retrotransposons, a type of parasitic DNA sequence, manipulates a cell’s DNA repair mechanism to form a ring-like structure and generate a corresponding double strand. This finding, published online in the journal Nature, refutes a 40-year old conventional understanding that these rings were merely redundant byproducts of inaccurate gene duplication.

“I think these elements are the source of genome dynamics, for animal evolution and even to affect our daily lives,” said Zhao Zhang, an assistant professor of pharmacology and cancer biology and a Duke Science & Technology scholar. “But we are still in the process of appreciating their function.”

Retrotransposons are DNA segments that replicate and insert themselves into various genome parts, contributing to DNA rewriting and gene regulation in both plants and animals. They are often implicated in evolutionary dynamics and can be inherited from both parents.

Furthermore, they have been associated with cancer development and progression, as they often carry oncogenes, genes that can lead to cancer when mutated or expressed at high levels. Circular DNA, a form known to be produced by the retrovirus HIV, which causes AIDS, has also been identified within these retrotransposons.

Retrotransposons are prevalent, comprising approximately 40% of the human genome and over 75% of the maize genome. However, the specifics of their replication have remained enigmatic.

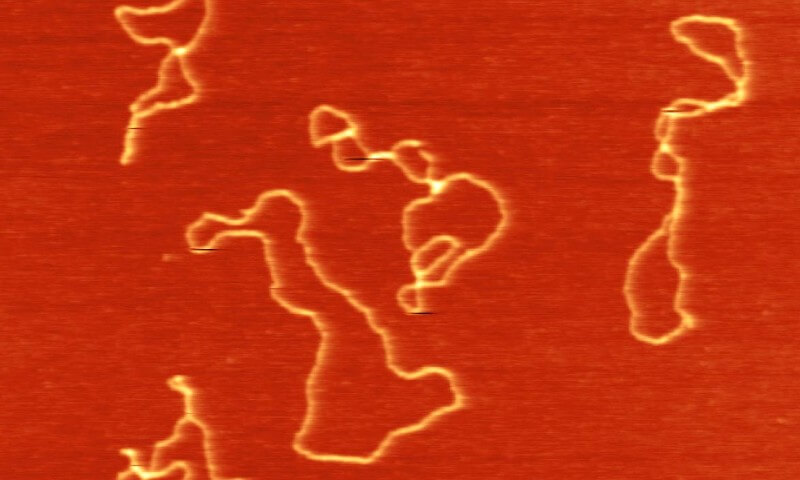

In previous research using fruit fly eggs, Zhang’s team found that retrotransposons exploit ‘nurse cells’ supporting the egg to proliferate and spread throughout the genome in the developing egg. Surprisingly, their recent research revealed that most newly inserted retrotransposons appeared in a circular rather than integrated form in the host’s genome.

Through a series of experiments disabling the cell’s DNA repair mechanisms, the researchers found that retrotransposons utilize a relatively unexplored DNA repair system called alternative end-joining DNA repair (alt-EJ). This mechanism repairs double-stranded breaks, allowing retrotransposons to connect the ends of their single-stranded DNA and form a matching double-strand, akin to the strategies employed by viruses.

“Our discovery actually overturns the textbook model,” Zhang said. “We showed that the recombination event proposed by the textbook is not important to forming rings. Instead, it’s the alt-EJ pathway driving circle production.”

Currently, Zhang’s lab is examining the possibility of circular DNA acting as an intermediate for new genome insertions and triggering an immune response.

“In the retroviral field and retrotransposon field, people think circular DNA is just a minor event, but our study is bringing circular DNA into the center stage,” Zhang said. “People should pay more attention to circular DNA.”

The study was funded by the National Cancer Institute (P01CA247773), National Institutes of Health (DP5 OD021355, R01 GM141018), and the Pew Biomedical Scholars Program. The study, “Retrotransposons Hijack alt-EJ for DNA Replication and eccDNA Biogenesis,” is available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-023-06327-7.