Herpes simplex virus (HSV) is extremely common, affecting nearly two-thirds of the world’s population, according to the World Health Organization.

Once inside the body, HSV establishes a latent infection that periodically awakens, causing painful blisters on the skin, typically around the nose and mouth. While a mere nuisance for most people, HSV can also lead to dangerous eye infections and brain inflammation in some people and cause life-threatening infections in newborns.

Researchers have long known that the virus and the host immune system are in a perpetual competition, but why does this battle reach a stasis in most people while causing serious infections in others?

More important, precisely how does the battle unfold at the level of cells and molecules? This question has continued to bedevil scientists and hamper the quest for treatments that prevent or cure infections.

A recent study by researchers at Harvard Medical School, conducted using lab-engineered cells and published in PNAS, unveils the precise maneuvers used by host and pathogen in the fight for dominance of the cell.

Furthermore, the research shows how the immune system keeps the virus at bay in a battle taking place at the control center of the cell — its nucleus.

Immune signaling proteins issue a call to arms

The research reveals a key role for a group of signaling proteins called interferons, which recruit other protective molecules and block the virus from establishing infection.

Once inside the host, HSV multiplies by making copies of itself inside the nuclei of cells, using the host’s genetic machinery. For that to happen, the virus must outcompete the host’s immune system. But many of the tactics the virus and the immune system use in this contest have remained a mystery, making it challenging to design medicines to help patients defeat the virus.

Interferons — named for their ability to interfere with pathogens’ attempts to infect cells — are signaling molecules released when the immune system detects the presence of microbes, such as viruses. The distress signals sent by interferons activate genes in that cell and other cells that produce proteins, which in turn block viruses from establishing infection in the first place.

Several different mechanisms that interferons use to thwart viruses within the cytoplasm, the gelatinous liquid that fills cells, are well known. But how interferons work against DNA viruses — those launching their attack within the cell nucleus — has remained elusive.

“We know a lot about how interferon and immune stimulants work against viruses in the cytoplasmic body of the cell, but up until now, we knew very little about how the immune system blocks viral infection in the cell’s nucleus,” said study senior author David Knipe, the Higgins Professor of Microbiology and Molecular Genetics in the Blavatnik Institute at HMS. “Our findings define the mechanisms of action of any treatment that induces interferons and how they can prevent and treat infections from HSV, as well as other herpesviruses and nuclear DNA viruses.”

Knipe said the insights from this work could also help researchers understand — and perhaps eventually develop treatments for — other nuclear DNA viruses, including well-known troublemakers like the Epstein-Barr virus, which causes mononucleosis; human papillomavirus; hepatitis B; and smallpox.

These results define the mechanisms of action of interferon treatments for herpesvirus diseases and other treatments such as toll-like receptor ligands that have been tested for herpes, the researchers said. Other new activators of interferons such as cGAS agonists could also be used to induce herpes resistance through the newly defined mechanisms, the researchers added.

The researchers caution that any new potential therapies for HSV and other DNA viruses are purely conceptual at this point. Any such approaches should be first tested in small animals such as mice, then in larger animals and, finally, in humans.

Mapping the steps of a viral arms race

In the new study, Knipe and co-author Catherine Sodroski, an HMS PhD graduate now at the National Institutes of Health, discovered that a host protein called IFI16 is recruited by interferon to help block the virus from reproducing in several ways.

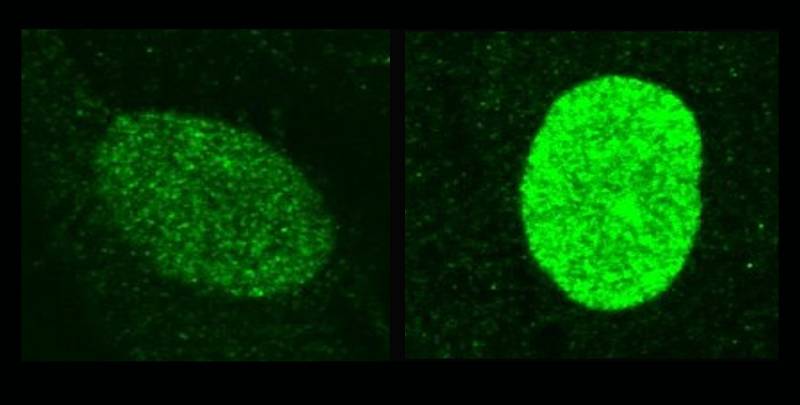

One of the strategies used by IFI16 to fend off HSV involves building and maintaining a shell of molecules around the viral DNA genome. This molecular “bubble wrap” prevents the virus from unfurling. With the virus wrapped up, it can’t activate its DNA to express its genes and make copies of itself.

To counter these protective maneuvers, however, the virus produces molecules called VP16 and ICP0 that can remove the wrapping, deactivate the host cell’s protective molecules, and enable the virus to reproduce.

Another mechanism used by IFI16 to fight HSV infection is to neutralize VP16 and ICP016 . Under normal circumstances, when the cell is not preparing to repel a viral invader, there is some IFI16 present within the nucleus. But this background level of IFI16 isn’t enough to fight off the viral helper proteins and keep the virus wrapped and restrained.

Without interferon’s call to the cell to send in more IFI16, the virus wins the arms race and infects the cell. However, the experiments showed, when interferon signals recruit higher levels of IFI16, the immune system wins.

This current study echoes similar findings that found elevated levels of IFI16 in clinical samples of tissues where the immune system appeared to be successfully controlling symptoms of the closely related HSV-2 virus, providing crucial insights about the molecular machinery at work in staving off outbreaks of symptoms.

Using insights from the lab to improve human health

Knipe says he became interested in the biology of herpesviruses as an undergraduate while recovering from a bout of mononucleosis. He turned that curiosity into a career.

The Knipe lab studies what happens at the level of molecules and cells when HSV causes symptomatic and dormant infections. He is particularly interested in how the host immune system responds to HSV. Knipe has applied the insights gained by studying HSV to explore the possibilities of using genetic material from HSV to deliver vaccines for HIV, SARS, West Nile, and anthrax.

“Solving the puzzles that underlie the basic biology of how these viruses interact with the host cell nucleus and immune system is endlessly fascinating, and finding new ways to apply that knowledge to fighting diseases is endlessly rewarding,” Knipe said. “The most exciting part is that we’re just scratching the surface of the deep knowledge we can tap into for this fight.”

Authorship, funding, disclosures

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health predoctoral fellowship F31 AI145062 and National Institutes of Health grant AI106934.

Related