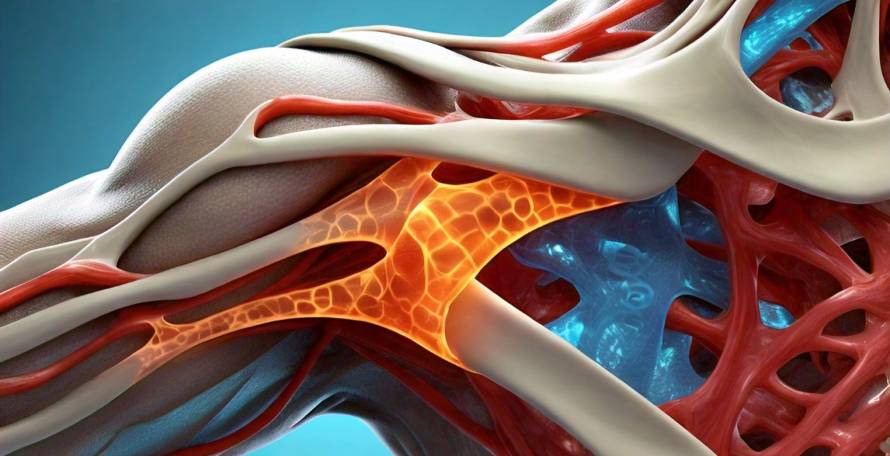

A new study from orthopedic scientists and biomedical engineers at Columbia University indicates that a common practice among shoulder surgeons of removing a tissue called the bursa during rotator cuff surgery may be hindering the success of the procedure. The study suggests that the small tissue plays a role in helping the shoulder heal after surgery.

The Prevalence of Rotator Cuff Injuries

Rotator cuff injuries are common, particularly among people over 65, with about half having experienced a rotator cuff tear. These injuries can make simple daily tasks painful and difficult. In the United States, more than 500,000 rotator cuff surgeries are performed each year to repair these injuries, restore range of motion, and alleviate pain. However, these surgeries frequently fail, with failure rates ranging from 20% in young patients to as high as 94% in elderly patients with large tears.

“It is common to remove the bursa during shoulder surgery, even for the simple purpose of visualizing the rotator cuff,” says Stavros Thomopoulos, PhD, the study’s senior author and the Robert E. Carroll and Jane Chace Carroll Laboratories Professor of Orthopaedic Surgery at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons. “But we really don’t know the role of the bursa in rotator cuff disease, so we don’t know the full implications of removing it.”

The Bursa’s Role in Rotator Cuff Health

To explore the role of the bursa in rotator cuff disease, Thomopoulos and graduate student Brittany Marshall examined rats with repaired rotator cuff injuries, with and without bursa removal. They found that the presence of the bursa protected the undamaged tendon by maintaining its mechanical properties and protected the bone by maintaining its morphometry. When the bursa was removed, the strength of the undamaged tendon and the quality of the bone deteriorated.

In the damaged tendon, the researchers found that the bursa promoted an inflammatory response and activated wound healing genes. While no changes were seen in the mechanical properties of the repaired tendon two months after the repair, Thomopoulos suggests that differences may be detected after a longer healing period.

The researchers also explored the possibility of using the bursa as a drug delivery depot by injecting corticosteroid microspheres into the bursa of their rat model after tendon injury. Although the treatment results are preliminary, the initial data supports the idea that the bursa can be therapeutically targeted to improve rotator cuff healing.

“Overall, what we’re seeing is a beneficial role of the bursa for rotator cuff health, in contrast with the historical view that the inflamed bursa is detrimental,” says Thomopoulos.