Researchers at Duke Health have made a remarkable discovery that could potentially turn back the clock on liver damage. Their study, published in Nature Aging, shows how stress and aging-related liver damage might be reversible, offering new hope for millions suffering from non-alcoholic liver disease.

Unraveling the Mystery of Liver Aging

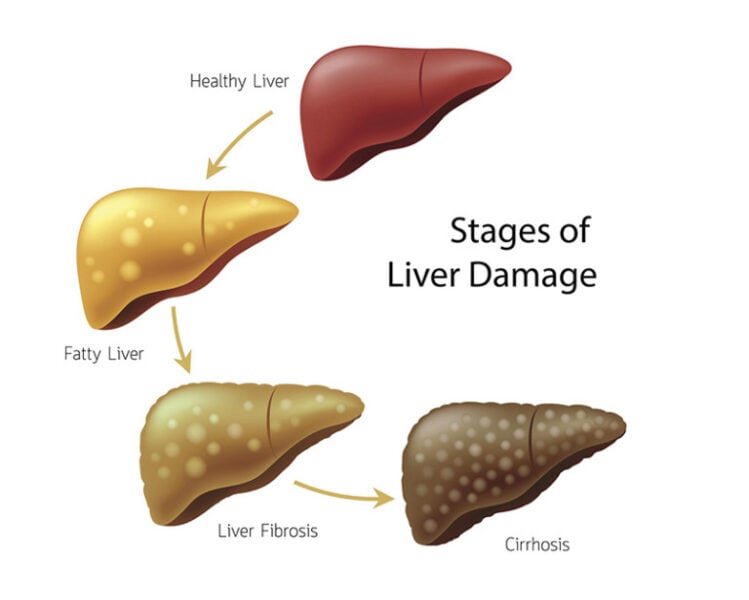

The research team, led by Dr. Anna Mae Diehl, focused on understanding how non-alcoholic liver disease progresses to cirrhosis, a severe condition characterized by scarring that can lead to organ failure. They found that aging is a key risk factor for cirrhosis in patients diagnosed with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), which affects one in three adults worldwide.

By studying mouse livers, the researchers identified a genetic signature unique to old livers. These older organs showed an abundance of genes activated to cause degeneration of hepatocytes, the liver’s main functioning cells.

“We found that aging promotes a type of programmed cell death in hepatocytes called ferroptosis, which is dependent on iron,” Diehl explained. “Metabolic stressors amplify this death program, increasing liver damage.”

From Mice to Humans: A Promising Discovery

The team then analyzed human liver tissue and found that livers of people with obesity and MASLD carried the same genetic signature. The more severe the disease, the stronger the signal. This discovery provided researchers with a definitive target for intervention.

In a groundbreaking experiment, the researchers fed young and old mice diets that caused them to develop MASLD. Half the animals were given a placebo, while the other half received a drug called Ferrostatin-1, which inhibits the cell death pathway.

The results were astonishing. The livers of animals treated with Ferrostatin-1 looked biologically like young, healthy livers – even in older mice kept on the disease-inducing diet.

“This is hopeful for all of us,” Diehl said. “It’s like we had old mice eating hamburgers and fries, and we made their livers like those of young teenagers eating hamburgers and fries.”

The implications of this research extend beyond the liver. The team found that the ferroptosis process in the liver impacts the function of other organs often damaged as MASLD progresses, including the heart, kidneys, and pancreas.

While further research is needed to translate these findings to human treatments, this study opens up exciting possibilities for reversing liver damage and potentially improving overall health in patients with non-alcoholic liver disease. As Dr. Diehl concluded, “Our study demonstrates that aging is at least partially reversible. You are never too old to get better.”