The first-ever archaeological study conducted in space has revealed surprising insights into how astronauts actually use the International Space Station (ISS). This groundbreaking research sheds light on the adaptations and behaviors of humans living in microgravity, potentially influencing the design of future space habitats.

From Earth to Orbit: Adapting Archaeological Methods for Space

Researchers from the International Space Station Archaeological Project (ISSAP) have successfully applied terrestrial archaeological techniques to study life aboard the ISS. Led by Justin Walsh of Chapman University, the team developed an innovative approach to observe and analyze how astronauts utilize different areas of the space station.

“The experiment is the first archaeology ever to happen off of the planet Earth,” Walsh explained. “By applying a very traditional method for sampling a site to a completely new kind of archaeological context, we show how the ISS crew uses different areas of the space station in ways that diverge from designs and mission plans.”

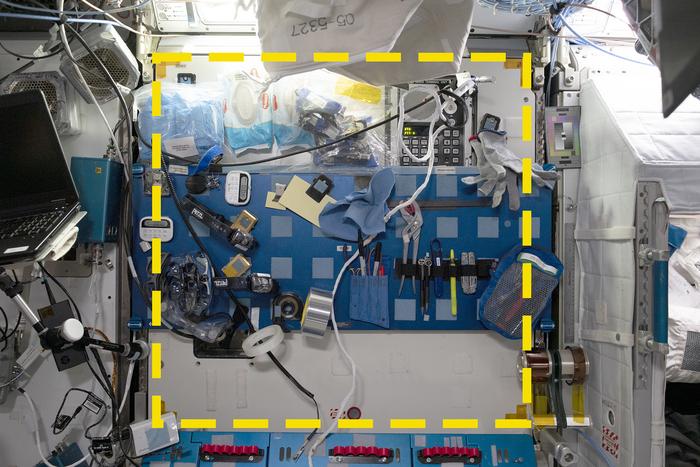

Instead of digging traditional shovel test pits, the researchers asked ISS crew members to document six locations around the station by taking daily photographs of each site for 60 days in 2022. This clever adaptation of archaeological methods allowed the team to gather valuable data without interfering with the astronauts’ work or compromising the integrity of the space station.

Uncovering the Hidden Life of Space Artifacts

The study, published in the journal PLOS ONE, focused on two key areas of the ISS: a space designated for equipment maintenance and another near the latrine and exercise equipment. Using a novel open-source image analysis platform developed by the team, researchers identified 5,438 instances of “artifacts” being used for various purposes.

These artifacts included everyday items such as writing tools, Post-It notes, and even an augmented reality headset. By cross-referencing the photographic data with astronaut activity reports, the researchers made some intriguing discoveries:

1. The area near the exercise equipment and latrine, while not officially designated for any particular use, had become an impromptu storage space for toiletries, resealable bags, and a seldom-used computer.

2. The equipment maintenance area was primarily used for storage, with little to no actual maintenance work being carried out there.

These findings highlight the ways in which astronauts adapt their environment to suit their needs, often diverging from the intended use of specific areas as outlined in mission plans.

Why it matters: Understanding how astronauts actually use and adapt their living space in microgravity is crucial for designing more efficient and comfortable habitats for future long-duration space missions. This research could inform the development of spacecraft for missions to the Moon, Mars, and beyond.

The study also demonstrates the potential for applying archaeological techniques to other extreme environments on Earth, such as Antarctic research stations or high-altitude settlements. By studying how humans adapt to these challenging conditions, we can gain valuable insights into our species’ resilience and ingenuity.

As space exploration continues to advance, the role of space archaeology is likely to grow in importance. Walsh, who is also a co-founder of Brick Moon, a consultancy in space habitat design and use, emphasized this point: “Archaeology is not just about the very distant past. It’s about using objects, artifacts, built spaces and architecture as primary evidence for how humans behave, interpret and adapt to the world around them. Archaeology has a place in space.”

Future research directions may include expanding the study to cover more areas of the ISS, conducting longer-term observations, and potentially applying similar techniques to other space habitats as they are developed. The insights gained from this pioneering work could revolutionize our approach to designing and operating spacecraft, ensuring that future astronauts have living spaces that are not only functional but also adaptable to their evolving needs.