Summary: Researchers at the University of Zurich have discovered that using CRISPR gene editing to treat a rare immune disorder can lead to unexpected chromosomal damage, even when using methods thought to be safer. The study reveals important safety considerations for gene therapy treatments, particularly when targeting genes that have similar copies in the genome.

Journal: Communications Biology, October 9, 2024, DOI: 10.1038/s42003-024-06959-z | Reading time: 6 minutes

The Promise and Peril of Genetic Scissors

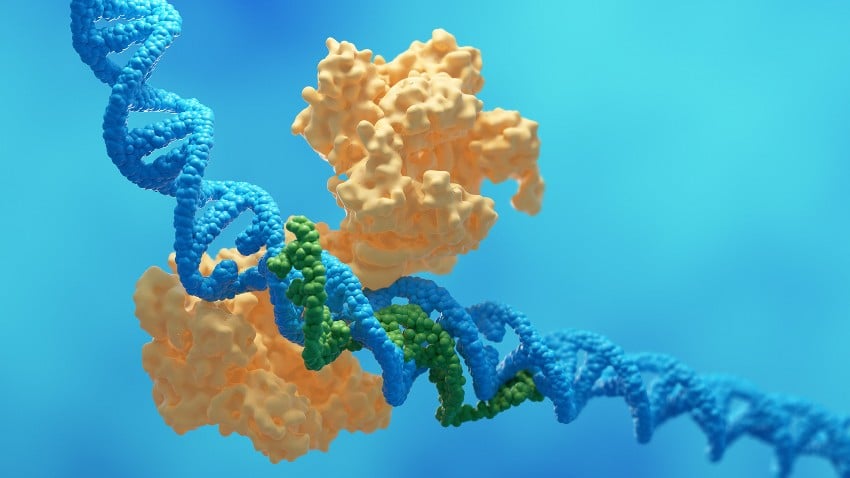

Scientists working to cure a rare immune disorder have uncovered important safety concerns about CRISPR gene editing, highlighting the challenges in using this revolutionary technology to treat genetic diseases. Their research reveals that even supposedly safer versions of the CRISPR system can accidentally cause substantial chromosomal damage when used to repair certain types of genetic defects.

The study focused on treating chronic granulomatous disease (CGD), a rare inherited condition affecting about one in 120,000 people that severely weakens the immune system. People with CGD are highly susceptible to serious infections because their immune cells can’t properly fight bacteria and fungi.

When Precision Tools Face Complex Challenges

The research team, led by Professor Janine Reichenbach at the University Children’s Hospital Zurich, attempted to correct a specific genetic defect that causes CGD. The challenge they faced was unusually complex: the defective gene has two nearly identical copies (called pseudogenes) sitting nearby on the same chromosome.

“This study highlights both the promising and challenging aspects of CRISPR-based therapies,” says study co-author Martin Jinek, a professor at the University of Zurich’s Department of Biochemistry.

Unexpected Chromosomal Damage

When the researchers used CRISPR to repair the defective gene, they discovered that the genetic scissors couldn’t distinguish between the real gene and its copies. This led to CRISPR accidentally cutting the DNA in multiple places simultaneously, sometimes causing large sections of the chromosome to be misaligned or lost entirely.

Even more concerning was the discovery that supposedly safer versions of CRISPR, which only make single cuts in the DNA, could still cause similar chromosomal damage. The medical consequences of such genetic rearrangements are unpredictable and could potentially contribute to the development of leukemia.

Search for Safer Solutions

The research team tested several alternative approaches to minimize these risks, including modified versions of CRISPR components and protective elements designed to reduce multiple cuts. However, none of these measures completely prevented the unwanted side effects.

“This calls for caution when using CRISPR technology in a clinical setting,” Professor Reichenbach emphasizes. The team notes that further technological advances will be needed to make the method safer and more effective for future clinical applications.

Glossary

CRISPR: A gene-editing technology that works like molecular scissors to cut and modify DNA at specific locations.

Pseudogenes: Inactive copies of genes that have a very similar DNA sequence to the active gene but don’t produce functional proteins.

Chromosomal rearrangement: A change in chromosome structure where segments of DNA are relocated, deleted, or duplicated.

Chronic granulomatous disease (CGD): A rare inherited immune disorder that impairs the body’s ability to fight certain infections.

Quiz

- What is the main safety concern discovered about CRISPR in this study?

Answer: CRISPR can cause unexpected chromosomal damage when targeting genes that have similar copies nearby - How common is chronic granulomatous disease (CGD)?

Answer: It affects about one in 120,000 people - Why did the researchers have difficulty targeting only the defective gene?

Answer: The gene had two nearly identical copies (pseudogenes) nearby on the same chromosome - What happened when researchers tried “safer” versions of CRISPR?

Answer: They still caused similar chromosomal damage, despite being designed to be safer

Enjoy this story? Get our newsletter! https://scienceblog.substack.com/