A comprehensive new study reveals how the intestine maintains stability while adapting to environmental challenges, with researchers discovering a unique region of the colon controlled by immune signals. This finding could reshape our understanding of inflammatory bowel diseases and celiac disease.

Published in Nature | Estimated reading time: 6 minutes

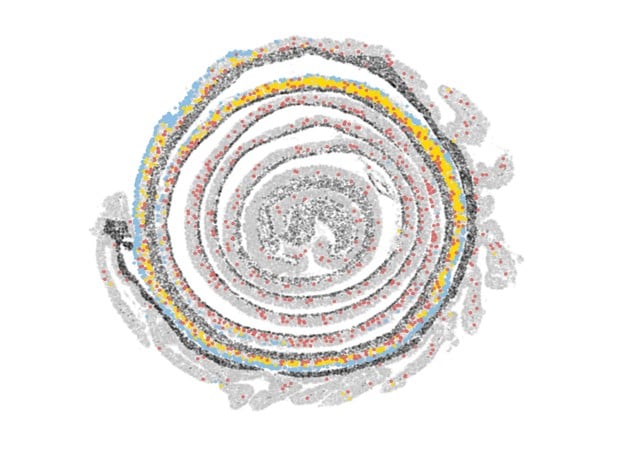

The intestine performs a delicate balancing act each day, absorbing nutrients while maintaining harmony with trillions of beneficial bacteria. Now, scientists have created the first detailed map of how this complex organ maintains its stability while adapting to environmental challenges.

Researchers at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard and Massachusetts General Hospital analyzed gene expression patterns across the entire mouse intestine, revealing surprising insights about the organ’s resilience and adaptability. Their findings could transform our understanding of various intestinal diseases.

“The intestine and in particular the colon has been studied for decades but it hasn’t been characterized in this way before,” explains Toufic Mayassi, co-first author of the study. “That both forces us to reevaluate many different studies and opens up a window for future research.”

The study revealed that the intestine’s cellular organization remains remarkably stable even when faced with significant changes. Whether in the presence or absence of gut bacteria, or during day or night cycles, the relative position and behavior of different cell types stayed consistent.

Perhaps most striking was the organ’s ability to bounce back from inflammation. When researchers induced inflammation, the intestine’s cellular patterns changed but showed signs of recovery after one month and had almost completely returned to normal within three months.

The team also discovered a unique region in the colon that responds to immune signals. This area contains specialized cells called goblet cells that produce protective mucus, but only when specific immune cells (ILC2s) are present. This finding highlights the sophisticated interplay between immune and structural cells in maintaining gut health.

“We’ve built a blueprint of the entire gut, and that’s a remarkable achievement,” notes Ramnik Xavier, senior author of the study. “We now have a way of studying the whole organ, examining the effect of genetic variants and immune responses associated with diet, the microbiome, and gastrointestinal disease.”

This research could prove particularly valuable for understanding conditions like celiac disease, ulcerative colitis, and Crohn’s disease, where the intestine’s normal balance is disrupted in specific regions.

Glossary:

- Spatial Transcriptomics

- A technique that maps gene activity across different locations in tissue, showing which genes are active where.

- Goblet Cells

- Cup-shaped cells in the intestine that produce protective mucus.

- ILC2s

- A type of immune cell that helps regulate intestinal function and inflammation.

What remained stable in the intestine despite environmental changes?

The spatial composition – the relative location of various cell types and the genes they express – remained stable despite changes in microbiota and circadian rhythms.

How long did it take for the intestine to almost completely recover from inflammation?

The intestine showed signs of recovery after one month and had almost completely recovered within three months.

What unique discovery was made about goblet cells in the colon?

They expressed certain genes only in the presence of ILC2s (specific immune cells), showing immune system control over structural cells.

Why is this research particularly significant for understanding intestinal diseases?

It provides insights into how different regions of the intestine respond to changes, which is crucial for understanding diseases that affect specific parts of the gut.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to our newsletter