Employing a combination of imaging and biomarker tests improves the ability of doctors to predict Alzheimer’s in patients with mild cognitive impairment, according to researchers at Duke Medicine.

The findings, which appear Tuesday, Dec. 11, 2012, in the journal Radiology, provide new insight into how to accurately detect Alzheimer’s before the full onset of the disease. Duke researchers studied three tests – magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), fluorine 18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET), and cerebrospinal fluid analysis – to determine whether the combination provided more accuracy than each test individually. The tests were added to routine clinical exams, including neuropsychological testing, currently used to diagnose Alzheimer’s disease.

“This study marks the first time these diagnostic tests have been used together to help predict the progression of Alzheimer’s. If you use all three biomarkers, you get a benefit above that of the pencil-and-paper neuropsychological tests used by doctors today,” said Jeffrey Petrella, MD, associate professor of radiology at Duke Medicine and study author. “Each of these tests adds new information by looking at Alzheimer’s from a different angle.”

“This study marks the first time these diagnostic tests have been used together to help predict the progression of Alzheimer’s. If you use all three biomarkers, you get a benefit above that of the pencil-and-paper neuropsychological tests used by doctors today,” said Jeffrey Petrella, MD, associate professor of radiology at Duke Medicine and study author. “Each of these tests adds new information by looking at Alzheimer’s from a different angle.”

Alzheimer’s disease affects more than 30 million people worldwide, and the number is expected to triple by 2050. Research suggests that Alzheimer’s begins years to decades before it is diagnosed, with patients experiencing a phase with some memory loss, or mild cognitive impairment, before the disease’s full onset. Patients with mild cognitive impairment are at a higher risk for having Alzheimer’s, but not everyone will progress to developing the disease.

While there is no cure for Alzheimer’s, new treatments under study are likely to be most effective at the disease’s earliest stages. Researchers are working to improve early detection of Alzheimer’s, even before patients experience symptoms, but the disease remains difficult to diagnose and patients are often misclassified.

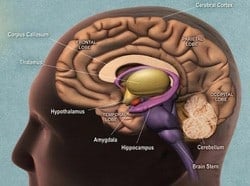

“Misdiagnosis in very early stages of Alzheimer’s is a significant problem, as there are more than 100 conditions that can mimic the disease. In people with mild memory complaints, our accuracy is barely better than chance. Given that the definitive gold standard for diagnosing Alzheimer’s is autopsy, we need a better way to look into the brain,” said P. Murali Doraiswamy, MBBS, professor of psychiatry and medicine at Duke and study author.

“Physicians vary widely in what tests they perform for diagnosis and prognosis of mild memory problems, which in turn affects decisions about work, family, treatment and future planning.”

The Duke team analyzed data from 97 older adults with mild cognitive impairment from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative, a national study that collects data in hundreds of elderly patients with varying levels of cognitive impairment. Participants took part in clinical cognitive testing, as well as the three diagnostic exams: MRI, FDG-PET, and cerebrospinal fluid analysis. They then checked in with doctors for up to four years.

The misclassification rate based solely on neuropsychological testing and other clinical data was relatively high at 41.3 percent. Adding each of the diagnostic tests reduced the number of misdiagnoses so that, with all three tests combined, researchers achieved the lowest misclassification rate of 28.4%.

Of the three individual diagnostic tests, FDG-PET added the most information to clinical testing to detect early Alzheimer’s in patients with mild cognitive impairment.

Researchers noted that while the tests clearly provided the most diagnostic information in combination, additional studies are needed to better understand their role in a clinical setting.

“The study used a unique data-mining algorithm to analyze MRI and PET images for ‘silent’ information that may not be apparent to the naked eye. Hence, the data should not be taken to mean that imaging should be done in every patient; rather, it sought to capture the maximum potential information available in the images,” Petrella said.

“Additional studies, including those looking at the cost effectiveness of these tests, are also needed to translate the most useful biomarkers into clinical practice.”

Earlier this year, a multicenter study led by Doraiswamy found that another type of PET scan that tags amyloid plaques in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s also helped predict the onset of the disease in those with mild cognitive impairment. Adding amyloid plaque imaging in future studies could supplement the tests used in this research, providing even more diagnostic information.

In addition to Petrella and Doraiswamy, study authors include Jennifer L. Shaffer, MD; Forest C. Sheldon, BS; Kingshuk Roy Choudhury, PhD; and R. Edward Coleman, MD (who died in June 2012) of the Department of Radiology at Duke University Medical Center. Vince D. Calhoun, PhD, of the Mind Research Network and the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering at the University of New Mexico, also authored this research.