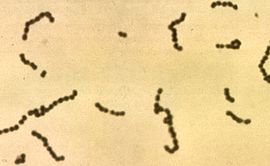

New research casts light on the interaction between the immune system and streptococcus bacteria, which cause both mild tonsillitis and serious infections such as sepsis and necrotising fasciitis.

The way in which antibodies attach to the bacteria is linked to how serious the disease is. Antibodies are key to the recognition and neutralisation of bacteria by our immune system. The most common antibodies have the shape of a Y, and the two prongs fasten to molecules that belong to the bacteria. The cells in the immune system recognise the shaft and can then attack the bacteria.

Since the 1960s, it has been known that certain bacteria have developed the ability to turn these antibodies around, which makes it more difficult for the immune system to identify them. These include streptococcus bacteria, sometimes referred to as ‘killer bacteria’, that cause both common tonsillitis and more serious diseases such as sepsis (blood poisoning) and necrotising fasciitis (flesh-eating disease). Because it has not been possible to study this phenomenon in detail, researchers have until now presumed that antibodies are always turned around in these streptococcal infections.

Since the 1960s, it has been known that certain bacteria have developed the ability to turn these antibodies around, which makes it more difficult for the immune system to identify them. These include streptococcus bacteria, sometimes referred to as ‘killer bacteria’, that cause both common tonsillitis and more serious diseases such as sepsis (blood poisoning) and necrotising fasciitis (flesh-eating disease). Because it has not been possible to study this phenomenon in detail, researchers have until now presumed that antibodies are always turned around in these streptococcal infections.

Now researchers at Lund University have shown that this is not the case. In less serious conditions, such as tonsillitis, the antibodies are back-to-front, but in more serious and life-threatening diseases such as sepsis and necrotising fasciitis, the antibodies are the right way round. These findings have now been published in the Journal of Experimental Medicine and completely alter the understanding of bacterial infections with several of our most common pathogenic bacteria.

“This information is important and fundamental to improving our understanding of streptococcal infections, but our results also show that the principle described could apply to many different types of bacteria”, says Pontus Nordenfelt, who is currently conducting research at Harvard Medical School in Boston.

The present study shows that it is the concentration of antibodies in the local environment in the body that controls how the antibodies sit on the surface of the bacteria. In the throat, for example, where the concentration is low, the antibodies sit the wrong way round, but in the blood, where the concentration is high, the antibodies are the right way round. This explains why the most serious infections are so rare in comparison to the common and often mild cases of throat and skin infections. The bacteria in the blood are quite simply easier for the immune system to find.

In the future, the results could have an impact on the treatment of serious infectious diseases, since a better understanding of the mechanisms behind the diseases is needed to develop new treatments.

Lars Björck, Professor of Infectious Medicine at Lund University, has discovered some of the antibody-turning proteins and has studied their structure and function for over 30 years.

“It is fantastic to have been involved in moving a major step closer to understanding the biological and medical importance of these proteins together with talented young colleagues”, he says.