Researchers at Johns Hopkins and elsewhere have brought new clarity to the picture of what goes awry in the brain during Parkinson’s disease and identified a compound that eases the disease’s symptoms in mice. Their discoveries, described in a paper published online in Nature Neuroscience on August 25, also overturn established ideas about the role of a protein considered key to the disease’s progress.

“Not only were we able to identify the mechanism that could cause progressive cell death in both inherited and non-inherited forms of Parkinson’s, we found there were already compounds in existence that can cross into the brain and block this from happening,” says Valina Dawson, Ph.D., the director of the Stem Cell Biology and Neuroregeneration Programs at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine’s Institute for Cell Engineering (ICE). “While there are still many things that need to happen before we have a drug for clinical trials, we’ve taken some very promising first steps.”

Dawson and her husband, Ted Dawson, M.D., Ph.D., the director of ICE, have collaborated for decades on studies of the molecular chain of events that leads to Parkinson’s. One of their findings was that the function of an enzyme called parkin, which malfunctions in the disease, is to tag a bevy of other proteins for destruction by the cell’s recycling machinery. This means that nonfunctional parkin leads to the buildup of its target proteins, and the Dawsons and others are exploring what roles these proteins might play in the disease.

In the new study, the Dawsons collaborated with Debbie Swing and Lino Tessarollo of the National Cancer Institute, to develop mice whose genes for a protein called AIMP2 could be switched into high gear. AIMP2 is one of the proteins normally tagged for destruction by parkin, so the genetically modified mice enabled the research team to put aside the effects of defective parkin and excesses of other proteins and look just at the consequences of too much AIMP2.

The consequences were that the mice developed symptoms similar to those of Parkinson’s as they aged, the group found. As in Parkinson’s patients, the brain cells that make the chemical dopamine were dying. Since AIMP2 is known for its role in the process of making new proteins, the researchers thought the cell death was caused by problems with this process. But when graduate student Yunjong Lee looked at the efficiency of protein-making in the affected mice, everything appeared normal.

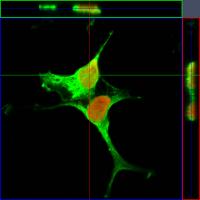

Looking for an alternative explanation, Lee tested how cells with excess AIMP2 responded to compounds blocking various paths to cell death, and found that the AIMP2 was activating a self-destruct pathway called parthanatos, discovered and named by the Dawsons years ago for the for poly(ADP-ribose), or “PAR,” and the Greek word thanatos, which means “messenger of death.”

The Dawsons had previously seen parthanatos set off after events like traumatic injuries or stroke — not by chronic disease. And there were more surprises to come. Lee found that AIMP2 triggered parthanatos by directly interacting with a protein called PARP1, which was long thought to respond only to DNA damage — not to signals from other proteins. Valina Dawson notes that AIMP2 is actually the second protein found to activate PARP1, but the idea that PARP1 is only involved in detecting and responding to DNA damage is still firmly entrenched in her field.

Since the Dawsons had been studying PARP1 for some time, they knew of compounds drug companies had designed to block this enzyme. Such drugs are already in the process of being tested to protect healthy cells during cancer treatment. Crucially, two of these compounds can cross over the blood-brain barrier that keeps many drugs from affecting brain cells. The research team used a compound that blocks PARP1, and Lee tested it on the mice with too much AIMP2. “Not only did the compound protect dopamine-making neurons from death, it also prevented behavioral abnormalities similar to those seen in Parkinson’s disease,” Lee says.

Though the results are encouraging, Valina Dawson cautions that there are hurdles that will need to be overcome before either of the brain-accessible compounds has a chance to make it into clinical trials. More extensive animal testing will need to be done, and with mice whose Parkinson’s symptoms don’t arise from genetically amped-up AIMP2 production. In addition, Dawson explains, in order for trials on any Parkinson’s drugs to run effectively, measurable markers of the disease’s severity need to be found. Ted Dawson and others at Johns Hopkins say they are now working on a separate project to do just that.