A new analysis of archived appendix samples suggests that 1 in 2,000 people in the United Kingdom may carry the abnormal prion protein (PrP) associated with variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (vCJD), a much higher prevalence than would be suspected from the small number of confirmed cases in the country.

The study, described in BMJ, raises questions about how many more cases may emerge in the country and about the risk of transmission of vCJD from apparently healthy carriers of the bnormal protein to others via blood donation and surgical procedures, say the authors.

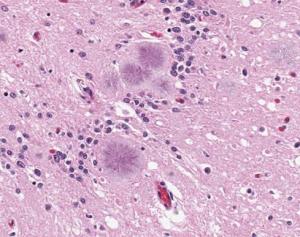

Variant CJD is the human form of bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE), or mad cow disease. BSE spread through British cattle herds in the 1980s and 1990s, and consumption of tainted beef was believed to be the cause of scores of vCJD cases. The BMJ report says the UK has had 177 such cases, but only 1 in the past 2 years.

The new study builds on a previous one, published in 2004, in which researchers tested 12,674 appendix samples and found 3 that contained the abnormal PrP. That suggested the prevalence of the protein in the UK was 237 per million population.

This time the researchers looked at samples from 41 hospitals that participated in the earlier survey, plus others from regions that had few participants in the survey. Out of 32,441 appendix samples, 16 were positive for abnormal PrP. That indicated a population prevalence of 493 per million (95% confidence interval, 282 to 801 per million).

The report says the finding translates into 1 carrier in 2,000 people, versus 1 in 4,000 in the earlier survey. The authors say the ranges of estimates from the two surveys largely overlap, suggesting the difference is not significant.

The researchers say they found no significant difference in prevalence between the sexes, the three geographic areas sampled, or earlier and later birth groups: 1941 to 1960 and 1961 through 1985. They also found that a particular genotype that has been found in all vCJD cases (being homozygous for methionine at codon 129 of the PrP gene) was seen in only half of the 16 positive samples.

The results point to a growing discrepancy between the prevalence of vCJD prions in the population and the relatively low number of vCJD cases, even if only the samples with the genotype seen in the clinical cases are counted, the scientists write.

“Nevertheless, these data are in keeping with recent animal experiments, which suggest that the human transmission barrier for [BSE] may be high for clinical disease but substantially lower for peripheral lymphoreticular infection,” they state.

The findings raise several difficult questions, the researchers add. One unknown is whether those who have the abnormal PrP but not the genotype associated with clinical disease are protected from vCJD. Another is whether carriers of the protein might transmit the disease through surgical procedures or by giving blood or other tissue.

Data from studies in sheep suggest that infective PrP can be present in blood early in the incubation period, but it is not known whether abnormal PrP in human lymphoreticular tissue means the protein is also present in blood, the scientists say. They add that it is essential to continue research on tests to detect abnormal PrP in blood.

In an accompanying BMJ editorial, Roland Salmon, a retired consulting epidemiologist and chair of the UK government’s Transmissible Spongiform Encephalopathies Risk Management Subgroup, writes that vCJD has been spread by blood products from donors who later were found to have the disease, but no clear case of vCJD transmission through surgery has yet been documented.

Salmon says that if infection with vCJD prions is common, “then precautionary measures are likely to be in place for a long time.” People who are believed to have an increased risk of CJD include those who have received blood from someone with CJD or have been operated on with surgical instruments that were used on someone with CJD.

These patients’ risk is thought to be high enough that they could pass the disease to others, Salmon writes. Therefore they are barred from giving blood, and special precautions must be taken in any surgery that involves tissues in which PrP might be found.

In an Oct 15 Nature news story on the study, experts said no one knows the risk of eventual clinical disease in asymptomatic people who have the abnormal PrP in lymphoid tissue. “We have no idea if none or a proportion of these people will develop clinical disease, that remains to be seen,” said Graham Jackson, a researcher in molecular diagnostics at the Medical Research Council Prion Unit at University College London.

Gill O, Spencer Y, Richard-Loendt A, et al. Prevalent abnormal prion protein in human appendixes after bovine spongiform encephalopathy epizootic: large scale survey. BMJ 2013 (early online publication Oct 15) [Full text]

Salmon R. How widespread is variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease? BMJ 2013;347:f5994 (early online publication Oct 15) [Full text]