Saint Louis University researchers are studying whether ReoPro® (abciximab), a drug currently given to heart patients undergoing angioplasties to open blocked arteries, also could help children and young adults who have severe pain from sickle cell disease.

“Sickle cell crises, which are acute episodes that can land patients in the hospital, can be excruciatingly painful,” said William Ferguson, M.D., director of the division of pediatric hematology and oncology at Saint Louis University and a SLUCare pediatrician at SSM Cardinal Glennon Children’s Medical Center.

“The typical vaso-occlusive crisis puts patients in the hospital for three to five days on intravenous medications. All we can do is give supportive care, such as pain killers, and wait for the crisis to run its course. Our research will tell us if using a medicine like ReoPro could be a valuable strategy in treating a sickle cell crisis.”

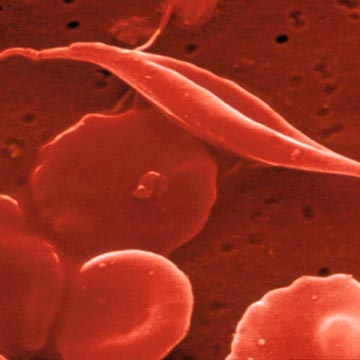

As reported in a news release issued by SLU, sickle cell crises occur when clots form in the small blood vessels, preventing blood from flowing freely to organs. Healthy red blood cells are shaped like flexible donuts and can fold to easily wiggle through the smallest blood vessels. Red blood cells in patients who have sickle cell disease are misshaped, crescent-like cells with sharp edges that get caught inside blood vessel walls and pile up to create blockages.

Much like an accident that impedes traffic on the road where it happened and on secondary feeder roads, sickle cell crises cause a second blood vessel blockage when red blood cells and platelets (small blood cells that stop bleeding) stick to the lining of the blood vessel walls.

“It’s like there’s a traffic accident and a quarter mile down the road, you slow down again. Right now, we don’t have anything that directly targets that secondary blockage,” Ferguson said. “These traffic pile ups can decrease blood flow and can damage the organ on the other side, such as the spleen, eyes or lungs.”

Ferguson, who is the study chair, said the research could represent a new approach to treating sickle cell crisis. He is leading a study that examines whether or not ReoPro could reduce the length of time patients who are having a sickle cell pain crisis spend in the hospital.

“As far as I know, no one has targeted the increased stickiness of both platelets and red blood cells in the context of a crisis,” Ferguson said. “We hope our research will tell us more about treating the disease and potentially open an avenue of research and drug development.”

Scientists from SLU’s Center for World Health and Medicine reviewed medical literature that identified the mechanism of action used by ReoPro as potentially promising in treating sickle cell crises because it attacks blockages in blood flow on two fronts. They then approached Ferguson about conducting the research, said Peter Ruminski, executive director of the center.

“ReoPro hits both of those proteins that affect the stickiness of platelets and the flow of red blood cells through the walls of the blood vessels. Our research will help us find out if medications that have similar properties can be effective against sickle cell disease,” Ruminski said.

“Sickle cell disease is a neglected disease that dramatically affects members of the St. Louis community who are African American. It is devastating for those who have it in terms of diminished quality of life and shortened lifespan.”

The Center for World Health and Medicine brokered the research project, which is the first clinical trial to come out of its work.

While ReoPro has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration to prevent clotting during angioplasty procedures, it has not been studied as a treatment for sickle cell disease. Janssen Biotech, Inc., the company that discovered and developed ReoPro, is donating the medication and providing funding for the study.

Ferguson is recruiting 100 patients who are between ages 5 and 25 for the double-blind randomized trial. Within 16 hours of being hospitalized for a sickle cell pain crisis, half will receive the investigational medicine and half a placebo. All will receive the standard of care, which includes pain medication, while they are in the hospital and released.

Researchers will track how long the volunteers remain in the hospital. Those in the study will be discharged from the hospital once their pain can be controlled by oral medications, provided they have no other medical problems. They will have a follow up visit with their hematologist a week to 10 days after leaving the hospital, which is routine care for those who have suffered a sickle cell crisis.

Sickle cell disease occurs in about one in 400 people of African descent and one in 4,000 Hispanics, affecting between 80,000 and 100,000 Americans. It varies in severity, with some people having significant pain from multiple crises. Typically, those who have sickle cell disease live to be in their 50s.

For some patients, the disease also interferes with the quality of life, Ferguson said.

“If you’re having multiple pain crises and going into the hospital many times a year, it’s hard to go to school or keep a job,” Ferguson said. “In addition, many people have moderate or minor crises in between hospitalizations and take narcotics to relieve the pain. That can compromise a person’s ability to function as well.”

Established in 1836, Saint Louis University School of Medicine has the distinction of awarding the first medical degree west of the Mississippi River. The school educates physicians and biomedical scientists, conducts medical research, and provides health care on a local, national and international level. Research at the school seeks new cures and treatments in five key areas: infectious disease, liver disease, cancer, heart/lung disease, and aging and brain disorders. The Center for World Health and Medicine is dedicated to developing therapies for rare (orphan) and neglected diseases.

To learn more about the sickle cell disease research at Saint Louis University, call (314) 577-5638.