Study suggests that social-network support for causes might be only a click deep

Social media may fuel unprecedented civic engagement. Digital networks might make possible mass protest and revolution – think “Arab Spring.” But sometimes and maybe even most of the time, a new study suggests, the accomplishments of online activism are much more modest.

Published in Sociological Science, the paper was co-authored by Kevin Lewis, of the University of California, San Diego’s department of sociology, with Kurt Gray, department of psychology at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and Jens Meierhenrich, department of international relations, London School of Economics and Political Science.

The researchers focused their attention on the “Save Darfur Cause” on Facebook. Causes.com is a free online platform for activism and philanthropy, and its Facebook application allows users to create, join and donate to a variety of causes, from helping survivors of natural disasters to aiding specific nonprofits more generally. At its height, the Save Darfur Cause – by the Save Darfur Coalition, seeking to end genocide in Sudan – was one of the largest on the social network.

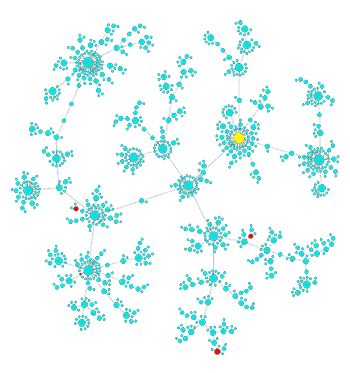

Lewis and colleagues analyzed the donation and recruitment activity of more than 1 million members of the Save Darfur Cause between May 2007 and January 2010. About 80 percent of the members had been recruited by other members and about 20 percent had joined independently.

Of these 1 million-plus members, 99.76 percent never donated any money and 72.19 percent never recruited anyone else.

The Save Darfur Cause on Facebook raised only about $100,000. While the average donation amounts were similar to more traditional fundraising methods ($29.06), the donation rate was much smaller: 0.24 percent. Compare that to mail solicitations which typically yield donation rates of 2 to 8 percent. The larger Save Darfur campaign, the researchers note, raised more than $1 million through direct-mail contributions in fiscal year 2008 alone.

Interestingly, those that had joined the Facebook cause independently were both more likely to donate and to recruit.

Social and financial contributions, though rare on both counts, also tended to go hand-in-hand. Those individuals that did recruit were nearly four times as likely as non-recruiters to donate. And donors were more than twice as likely as non-donors to recruit.

The data contained no demographic information on the cause’s members. Nor, the researchers write, could they estimate “the personal significance of [the joining] gesture to participants or the symbolic impact of the movement to onlookers.

“It is possible,” they add, “that the individuals in our data set contributed to Save Darfur in other meaningful but unobserved ways.”

Still, Lewis and colleagues believe the study gives some valuable insights into collective action in a digital age.

“The study is an important counter-balance to unbridled enthusiasm for the powers of social media,” said UC San Diego’s Lewis. “There’s no inherent magic. Social media can activate interpersonal ties but won’t necessarily turn ordinary citizens into hyper-activists.”

In the case of the Save Darfur campaign, the Causes Facebook app appears to have been “more marketing than mobilization,” Lewis said. It seems to have failed to convert the initial act of joining into a more sustained set of behaviors. For the vast majority of the members, he said, “the commitment might have been only as deep as a click.”