Nearly half of all adults in the United States suffer from the gum disease periodontitis, and 8.5 percent have a severe form that can raise the risk of heart disease, diabetes, arthritis and pregnancy complications.

University of Pennsylvania researchers have been searching for ways to prevent, half and reverse periodontitis. In a report published in the Journal of Immunology, they describe a promising new target: a component of the immune system called complement. Treating monkeys with a complement inhibitor successfully prevented the inflammation and bone loss that is associated with periodontitis, making this a promising drug for treating humans with the disease.

George Hajishengallis, a professor in the School of Dental Medicine’s Department of Microbiology, was the senior author on the paper, collaborating with co-senior author John Lambris, the Dr. Ralph and Sallie Weaver Professor of Research Medicine in the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine in the Perelman School of Medicine. Their collaborators included Tomoki Maekawa, Toshiharu Abe, Evlambia Hajishengallis and Kavita B. Hosur of Penn Dental Medicine and Robert A. DeAngelis and Daniel Ricklin of Penn Medicine.

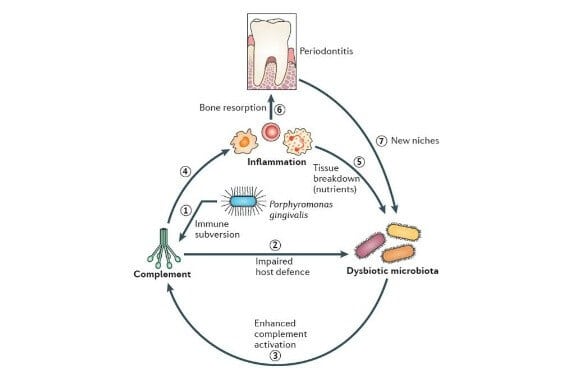

Earlier work by the Penn team had shown that the periodontal bacterium Porphyromonas gingivalis can hamper the ability of immune cells to clear infection, allowing P. gingivalis and other bacteria to flourish and inflame the gum tissue.

“P. gingivalis has many mechanisms to escape killing by the immune system, but getting rid of inflammation altogether is not good for them because they ‘feed’ off of it,” Hajishengallis said. “So P. gingivalis helps suppress the immune system in a way that creates a hospitable environment for the other bacteria.”

The researchers wanted to find out which component of the complement system might be involved in contributing to and maintaining inflammation in the disease. Their experiments focused on the third component of complement, C3, which occupies a central position in signaling cascades that trigger inflammation and activation of the innate immune system.

The team found that mice bred to lack C3 had much less bone loss and inflammation in their gums several weeks after being infected with P. gingivalis compared to normal mice. C3-deficient mice were also protected from periodontitis in two additional models of disease: one in which a silk thread is tied around a tooth, promoting the build-up of microbes, and one in which the disease occurs naturally in aging mice, mimicking how the disease crops up in aging humans.

“Without the involvement of a different complement component, the C5a receptor, P. gingivalis can’t colonize the gums,” Hajishengallis said. “But without C3, the disease can’t be sustained over the long term.”

Building on this finding, the researchers tested a human drug that blocks C3 to see if they could reduce the signs of periodontal disease in monkeys, which, unlike mice, are responsive to the human drug. They found that the C3 inhibitor, a drug called Cp40 that was development for the treatment of the rare blood disease PNH and ABO-incompatible kidney transplantation, reduced inflammation and significantly protected the monkeys from bone loss.

“We think this drug offers a promising possibility for treating adults with periodontitis,” Lambris said. “Blocking C3 locally in the mouth helps shift the balance of bacteria, producing an overall beneficial effect.”

According to the researchers, this study represents the first time, to their knowledge, that anyone has demonstrated the involvement of complement in inflammatory bone loss in non-human primates, setting the stage for translation to human treatments.

The results, Hajishengallis said, “provide proof-of-concept that complement-targeted therapies can interfere with disease-promoting mechanisms.”