As long as humans have been alive, they’ve been seeking ways to extend life just a little longer. So far no one has found the fountain of youth, but researchers have begun to understand how humans age, little by little, offering hope for therapies that may blunt the effects of time on the body.

In a new study, University of Pennsylvania scientists used innovative techniques to find evidence that oxidative damage in mitochondria — the small compartments in cells that convert food to energy — may play a role in the aging process.

Brett Kaufman, an assistant professor in the Department of Animal Biology in Penn’s School of Veterinary Medicine, was the senior author on the research, which was published in the journal Free Radical Biology and Medicine. Jill Kolesar, a postdoctoral researcher in Kaufman’s lab, was the study’s first author. Kaufman and Kolesar collaborated with a team from McMaster University in Canada that included Adeel Safdar, Arkan Abadi, Lauren MacNeil, Justin Crane and Mark Tarnopolsky.

Mitochondria are known as the “powerhouses” of cells. They convert what we eat into energy we use to grow, move and live. But mitochondria have another feature that makes them special: they contain their own genomes, in multiple copies. Unlike the nuclear genome, which is inherited from both mother and father, the mitochondrial genome is inherited only through the maternal line.

Though mitochondrial DNA is small in comparison with nuclear DNA — 16,000 base pairs as opposed to three billion — it is vital.

“It’s been reduced down so much over evolutionary time that few nucleotides can be varied,” Kaufman said. “When there is a sequence variation, a deletion or depletion in mitochondrial DNA, disease and pathology can develop.”

Indeed, research suggests that mitochondrial dysfunction plays a leading or supporting role in a variety of ailments, including heart disease, cancer, muscular dystrophy and Alzheimer’s disease. It’s also been linked to aging.

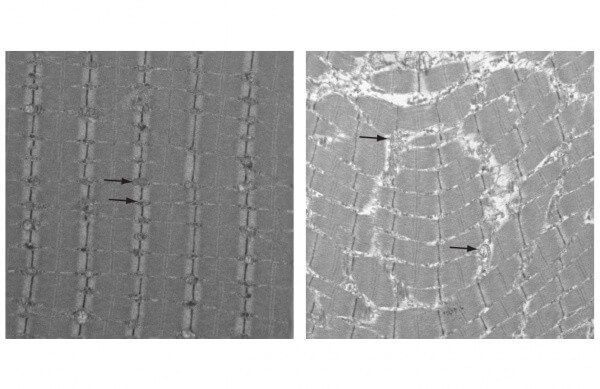

In the new study, Kaufman and colleagues examined a mutant mouse that has been bred to have dysfunctional mitochondria and, as a result, prematurely display characteristics of human aging. At just one year of age, which is early middle age for a mouse, these animals have gray hair, reduced muscle mass and heart disease.

Other researchers have studied this same line of mice but had not found evidence of oxidative stress, which occurs when mitochondria produce more reactive oxygen species, or ROS, than the cell can clear before damage occurs. The Penn-led team hypothesized that oxidative stress might be part of the reason why these mice aged prematurely.

“Ninety percent of the oxygen you breathe is used by mitochondria to make energy,” Kaufman said. “Sometimes electrons in that process go awry and can hit things they aren’t supposed to encounter, like the mitochondrial DNA, which is in close proximity. The theory is that, as we age, we generate more ROS and do more damage to the mitochondria, and this becomes a vicious cycle.”

The researchers used sophisticated techniques developed in Kaufman’s lab to closely study the mutant mice’s mitochondrial DNA. They found evidence of damage, including deletions, depletion and problems in replication. Subjecting muscle cells to additional oxidative stress led to similar results in a dose-dependent manner.

Although other researchers hadn’t seen markers of oxidative stress, when Kaufman and colleagues examined only the mitochondria from muscle cells in the mutant mice, they did see increased levels of proteins associated with oxidation when compared with normal mice. In addition, they found the mutant mice had reduced levels of major antioxidants, which are molecules that assist in the clearance of ROS from the tissue.

“We showed the first really solid evidence that in this mouse model there is in fact mitochondrial oxidative stress,” Kaufman said. “And when we look at molecular pathways related to detoxification, we find these mice have lower levels of activity. This is also what we see in aging and sedentary lifestyles.”

Though the team didn’t make a direct connection between oxidative stress and the defects seen in this mouse, their findings suggest that it is likely playing a role in aging. Preserving mitochondrial DNA content and integrity could thus be a strategy for combating age-related health decline.

“We could do this generally with antioxidants or more specifically by using compounds that target oxidation in the mitochondria,” Kaufman said.

The team’s next steps will be to use their new techniques to examine other disease models that involve mitochondrial defects, including heart disease, premature birth and diabetes. The study was supported by the Muscular Dystrophy Association, a Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia pilot award, the Canadian Institute of Health Research and a private donation.