Way too often, promising-looking basic-research findings – intriguing drug candidates, for example – go swooshing down the memory hole, and you never hear anything about them again. So it’s nice when you see researchers following up on an upbeat early finding with work that moves a potential drug to the next peg in the development process. All the more so when the drug candidate targets a massively prevalent disorder.

Type 2 diabetes affects more than 370 million people worldwide, a mighty big number and a mighty big market for drug companies. (Unlike the much less common type 1-diabetes, where the body’s production of the hormone insulin falters and sugar builds up in the blood instead of being taken up by cells throughout the body, in type-2 diabetes insulin production may be fine but tissues become resistant to insulin.) But while numerous medications are available, none of them decisively halt progression, much less reverse the disease’s course.

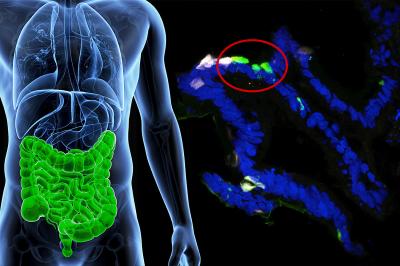

About two-and-a-half years ago, Stanford data-mining maven Atul Butte, MD, PhD, combed huge publicly available databases, pooled results from numerous studies and, using big-data statistical methods, fished out a gene that had every possibility of being an important player in type 2 diabetes, but had been totally overlooked. (For more info, see this news release.) Called CD44, this gene is especially active in fat tissue of insulin-resistant people and, Butte’s study showed, had a strong statistical connection to type-2 diabetes.

Butte’s study suggested that CD44′s link to type-2 diabetes was not just statistical but causal: In other words, manipulating the protein CD44 codes for might influence the course of the disease. By chance, that protein has already been much studied by immunologists for totally unrelated reasons. The serendipitous result is that a monoclonal antibody that binds to the protein and inhibits its action was already available.

So, Butte and his colleagues used that antibody in tests they performed on lab mice bioengineered to be extremely susceptible to type-2 diabetes, or what passes for it in a mouse. And, it turns out, the CD44-impairing antibody performed comparably to or better than two workhorse diabetes medications (metformin and pioglitazone) in countering several features of type 2 diabetes, including fatty liver, high blood sugar, weight gain and insulin resistance. The results appear in a study published today in the journal Diabetes.

Most exciting of all: In targeting CD44, the monoclonal antibody was working quite differently from any of the established drugs used for type-2 diabetes.

These are still early results, which will have to be replicated and – one hopes – improved on, first in other animal studies and finally in a long stretch of clinical trials before any drug aimed at CD44 can join the pantheon of type-2 diabetes medications. In any case, for a number of reasons the monoclonal antibody Butte’s team pitted against CD44 is far from perfect for clinical purposes. But refining initial “prototypes” is standard operating procedure for drug developers. So here’s hoping a star is born.