Ethical failure in a successful research project

If Victor Frankenstein had been forced to face an institutional review board in 1790 before he created his monster, would he ever have been able to begin his project to create a human life from the remaindered parts of dead bodies?

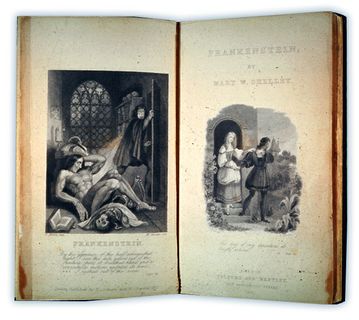

In a new paper published in the journal “Science and Engineering Ethics,” UNM English Professor Gary Harrison and Biology Research Assistant Professor and Research Ethics Compliance officer William Gannon have co-authored a paper that includes a mock Institutional Review Board proposal for research conducted by Frankenstein from Mary Shelley’s novel of the same name. “Victor Frankenstein’s Institutional Review Board Proposal, 1790” bases the proposal on the state of science at the time.

Institutional Review Boards (IRB) are a fact of life for every researcher working with human subjects at U.S. research universities. Every university has a board staffed by senior faculty members, who discuss and sometimes reject proposed research that doesn’t adequately protect research subjects.

In an interdisciplinary collaboration, Harrison and Gannon review the steps Frankenstein would have gone through with an IRB such as the one at the University of New Mexico. He would be required to submit a detailed statement on his scientific rationale for the experiment, an explanation of his objectives, aims and his hypotheses, and a description of his study design and procedures.

Further, he would have to submit a timeline, locations, some details on how he proposed to compensate his participant, list his resources, consider anticipated and unanticipated problems, and outline the expected risks and benefits to his university, the community and to science. Frankenstein would have to detail his target population, his participant’s privacy protection, and he would have to outline how he would share his study data and deliver details on how his participant would be able to withdraw from the study.

The article, showing the role that “Frankenstein” might play in teaching research ethics, emphasizes the way the novel that Mary Shelley wrote at the age of 19 continues to impact thinking about the way human research is conducted today. Emphasizing the moral and ethical questions raised by the research on a human subject, the novel vividly showed the public the negative consequences resulting from Frankenstein turning his back on family and friends in order to animate a human creature from lifeless matter, then rejecting his creature and ignoring his basic needs. The reading public immediately grasped the importance of the novel’s ethical and moral concerns, even as it highlighted and exaggerated Victor and his creature’s sinister aspect.

The article roots the IRB proposal in a quick synopsis of the development of the IRB, whose basic principles stem from actual cases of research that failed to consider the safety and welfare of human participants – most famously the human experiments performed on prisoners of war and civilian populations before and during World War II, which led to the Nuremberg trials and the Tuskegee Syphilis Study.

That involved experiments conducted by the U.S. Public Health Service on 600 African American men from rural communities near Tuskegee, Ala. There researchers failed not only to disclose to the participants that 399 of them had syphilis, but failed to treat them after penicillin became available for the disease. As a result many of them died and the disease spread to some families.

When the abusive practice was disclosed, the investigation led to the National Research Act of 1974. That resulted in the Belmont Report, which outlines the basis of current regulation of human experimentation.

The three basic principles in the Belmont Report are:

- Respect for the person.

- Beneficence or do no harm

- Justice or the fair sharing of the benefits of research

Today, the requirement for submitting IRB proposals is a tool universities use to ensure that researchers carefully think through the implications of their research – and to consider the possible consequences if it doesn’t go as expected. Although the IRB process may seem to be an obstacle for researchers, the article aims to show that IRB protocols ultimately benefit the researchers, the subjects, and their communities by creating an opportunity for researchers and their peers to think through the larger ethical implications of the research.

Since nearly everything Frankenstein did in the book as he conducted his research neglected the Belmont standards (as well as the Helsinki standards which govern research in Europe), Harrison and Gannon hope their example will benefit research ethics instructors and students at UNM and elsewhere, and cause them to consider the value of the IRB process in ensuring the welfare, safety and justice of human subjects involved in research. When you read Frankenstein’s mock proposal, it is dry, dispassionate, focused on the research goals, while acknowledging, but sometimes deferring the obvious moral and ethical problems that Shelley actually brings to the foreground in her novel.

People begin reading the paper to laugh at the absurdity of the idea of Frankenstein the scientist obsessed with his ideas, taking time to complete a bulky packet for forms that would slow him down and finish squirming uncomfortably at the all-too-close-to-home plausibility of an experiment, which focuses only on the actual research and ignores the possible repercussions to the creature’s anticipated and unanticipated needs.

It’s a lighthearted and unexpected look at a very serious subject.