To avoid the spread of Ebola and far worse scenarios, quick and forceful implementation of control interventions are necessary, according to new research published today in the scientific journal Eurosurveillance.

Analyzing Ebola cases in Nigera, a country that has had success in containing the disease, researchers estimated the rate of fatality, transmission progression, proportion of health care workers infected and the impact of control interventions on the size of the epidemic.

The study’s findings show that Ebola transmission is dramatically influenced by how rapidly control measures are put in place.

“Rapid and forceful control measures are necessary, as is demonstrated by the Nigerian success story,” said Arizona State University’s Gerardo Chowell, senior author of the paper. “This is critically important for countries in the West African region that are not yet affected by the Ebola epidemic, as well as for countries in other regions of the world that risk importation of the disease.”

Chowell is an associate professor in the School of Human Evolution and Social Change in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences.

Control measures in Nigeria

The largest Ebola outbreak to date is ongoing in West Africa, with approximately 8,011 reported cases that include more than 3,857 deaths as of Oct. 5. However, just 20 Ebola cases have been reported in Nigeria, with no new cases reported since Sept.5.

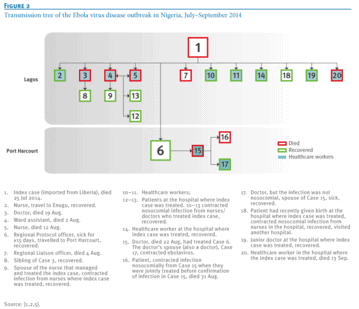

All of the cases stem from a single traveler returning from Liberia in July.

The study used epidemic modeling to project the size of the outbreak in Nigeria if control interventions had been implemented during various time periods after the initial case, and estimated how many cases had thus been prevented by early initiation of interventions.

Control measures enacted in Nigeria included all people showing Ebola symptoms being held in an isolation ward if they had contact with the initial case. Once Ebola was confirmed through testing, people with Ebola were moved to a treatment center.

Asymptomatic individuals were separated from those showing symptoms, and those who tested negative without symptoms were discharged. People who tested negative, but showed symptoms – fever, vomiting, sore throat and diarrhea – were observed and discharged after 21 days if they were free of symptoms, while being kept apart from people who tested positive for the disease.

“The swift control of the outbreak in Nigeria was likely facilitated by early detection of the initial case in combination with intense tracing efforts of all subsequent contacts that the person had after developing Ebola,” said Folorunso Oludayo Fasina, a senior scientist and lead author of the study at the University of Pretoria, South Africa.

“By contrast, the initial outbreak in Guinea remained undetected for several weeks, facilitating the spread of the virus to Sierra Leone and Liberia, where the inability to track and contain infectious individuals compounded the situation and resulted in an uncontrolled epidemic,” said the lead author.

Brief window of opportunity

Ebola transmission is dramatically influenced by how rapidly control measures are put in place, as researchers found that the projected effect of control interventions in Nigeria ranged from 15-106 cases when interventions are put in place on day 3; 20-178 cases when implemented on day 10; 23-282 cases on day 20; 60-666 cases on day 30; 39-1599 cases on day 40; and 93-2771 on day 50.

“There is brief window of time when a rapid and forceful intervention in terms of relentless contact tracing and isolation pays off handsomely and the transmission is effectively halted and the outbreak dies out,” said co-author professor Lone Simonsen, of the Milken Institute School of Public Health at the George Washington University in Washington D.C.

The person who was initially infected generated 12 secondary cases, in the first generation of the disease; five secondary cases were generated from those 12 in the second generation; and two secondary cases in the third generation, leading to a rough empirical estimate of the reproduction number according to disease generation declining from 12 during the first generation, to approximately 0.4 during the second and third disease generations. Recent estimates of the reproduction number for the ongoing Ebola epidemic in Sierra Leone and Liberia range between 1.5 and 2 (two new cases for each single case), indicating that the outbreak is yet to be brought under control.

“The effectiveness of the Nigerian response is illustrated by a dramatic decrease in the number of secondary cases over time. Overall, this is a great success story for Nigeria, which sets a hopeful example for other countries, including the U.S., which face risk of importation from high Ebola transmission areas,” said Cécile Viboud, a National Institutes of Health scientist with the Fogarty International Center.