Researchers may have developed a way to potentially assist prognostication in the first 24 hours after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) when patients are still in a coma. Their findings are revealed today at Acute Cardiovascular Care 2014 by Dr Jakob Hartvig Thomsen from Copenhagen, Denmark.

Acute Cardiovascular Care is the annual meeting of the Acute Cardiovascular Care Association (ACCA) of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and takes place 18-20 October in Geneva, Switzerland.

Dr Thomsen said: “When we talk to relatives and friends immediately after a cardiac arrest we often tell them that we’re not able to say much about the prognosis for their Dad, Mom, friend, etc, for the next 3 to 4 days. This is incredibly distressing and loved ones are desperate for more information.”

He added: “Therapeutic hypothermia is used in comatose survivors of OHCA to protect them from brain damage. Current recommendations say that prognostication should not be made until 72 hours after hypothermia when patients have returned to normothermia and the sedation has worn off.1 The prognostic tools presently available are not reliable until after this 72 hour period.”

Dr Thomsen continued: “During hypothermia some patients lower their heart rate, which is called bradycardia. We hypothesised that this is a normal physiological reaction and that these patients may have less severe brain injury after their arrest and therefore lower mortality.”

The study was conducted in the intensive care unit at Copenhagen University Hospital during 2004-2010 and was supported by the EU Interreg IV A programme. It included 234 comatose survivors of OHCA who underwent the hospital’s standard 24 hour therapeutic hypothermia protocol. Heart rhythm was measured hourly and sinus bradycardia (defined as less than 50 heart beats per minute) was used to stratify the patients. The primary endpoint was 180 day mortality.

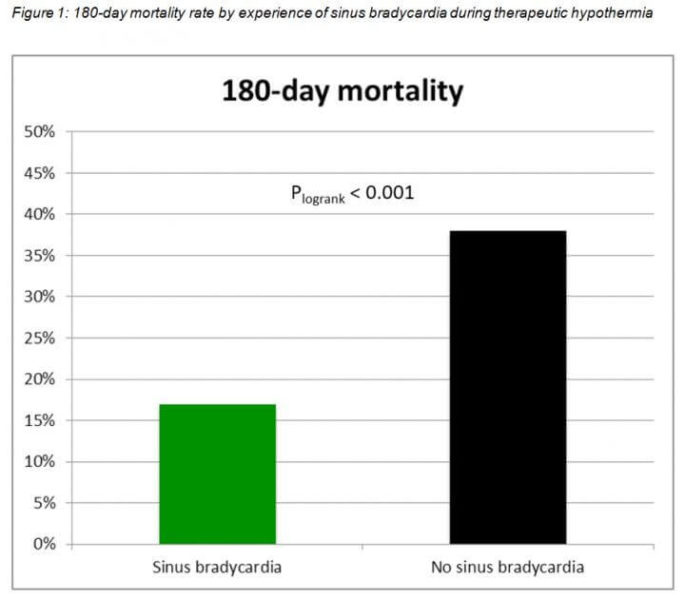

The investigators found that patients who experienced sinus bradycardia during therapeutic hypothermia had a 17% 180 day mortality rate compared to 38% in those with no sinus bradycardia (p<0.001) (figure 1), with a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.38. Sinus bradycardia during therapeutic hypothermia remained an independent predictor of lower 180 day mortality with a HR of 0.51 after adjusting for known confounding factors including sex, age, comorbidity, witnessed arrest and bystander CPR.

Dr Thomsen said: “Patients with sinus bradycardia during therapeutic hypothermia had a 50-60% lower mortality rate at 180 days than those with no sinus bradycardia. We also found that sinus bradycardia was directly associated with a better neurological status 180 days after the arrest.”

Few patients are in sinus bradycardia when they arrive at the intensive care unit (a period called the induction phase). However the proportion rises during hypothermia to almost 50%, and then declines during the rewarming phase.

Dr Thomsen said: “We speculated that this proportion of patients who develop sinus bradycardia during hypothermia would have better brain function and a lower mortality rate, and that was what we found. ”

He added: “Now when we observe that a patient experiences sinus bradycardia below 50 beats per minute within the first 24 hours we can tell families that their relative may have a chance of recovery.”

Dr Thomsen continued: “There is a lot of discussion about defining criteria to identify patients we should stop treating when a vegetative state is inevitable. We shouldn’t give up on patients who still have a chance so this is an area in which we need to be very certain. Our findings provide an early marker of patients who may do well. Hopefully in the future, together with other tools, we will be able to differentiate between those with a very good or very poor prognosis so we can prioritise intensive care resources.”

He concluded: “We are currently validating our findings by conducting the same analysis in the 950 patients included in the Targeted Temperature Management trial which was conducted in 36 intensive care units.”