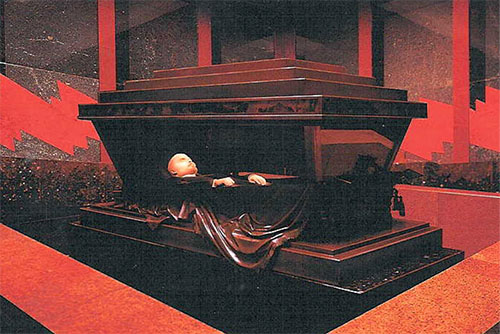

For 90 years, the embalmed corpse of Russian revolutionary Vladimir Lenin has been on public display in a mausoleum in Moscow’s Red Square, looking remarkably supple considering he died in 1924 at age 53. But ever since the Soviet Union collapsed a quarter-century ago, a debate has raged in Russia over whether to move the founder of the Soviet state to a more private location, leave him as is or bury his body once and for all.

UC Berkeley social anthropologist Alexei Yurchak, who for years has studied the science and politics surrounding the unprecedented preservation of Lenin’s corpse, believes it’s unlikely the body will be moved in the near future.

“You cannot replace Lenin,” says Yurchak, who is writing a book about how extraordinary body-preservation methods developed by Russian scientists helped the Soviet government transform Lenin’s body into a national icon. “Lenin’s body served as a kind of a material anchor in which the sovereignty of the Soviet communist project was grounded. But since the Soviet state’s collapse, while no longer the center of sovereignty, Lenin’s body remains important for other symbolic reasons.”

A native of Russia with a graduate degree in physics and a Ph.D. in anthropology, Yurchak is the author of many publications, including the award-winning 2005 book Everything Was Forever, Until It Was No More: The Last Soviet Generation.

While researching that book, Yurchak became intrigued by what he learned about Lenin’s symbolic importance to the Soviet Union. He has begun a second book, expected to hit shelves in 2017, that delves into the nearly century-old alliance between Russian politicians and scientists that keeps Lenin’s body looking so pristine.

Akin to the Declaration of Independence?

Yurchak likens the role that Lenin’s body played during the Soviet era to that of the Declaration of Independence, founding document of the United States. As initiator of the Soviet state and its big-bang revolution, in many ways Lenin and his physical body held the same symbolic power for Soviet citizens, whether communists or not, that the original paper document of the Declaration of Independence does for Americans.

In looking at how early measures taken by Soviet scientists to maintain Lenin’s body metamorphosed into a systematic preservation protocol, Yurchak marvels at their ability to combine advanced embalming techniques with the use of synthetic materials to replace body parts.

“They fix his body so it’s kind of authentic, but kind of not,” Yurchak says.

Lenin was born in Simbirsk to well-educated parents. As a young man he became a Marxist and later a firebrand who eventually led the revolution that birthed the Soviet state in 1917. The next year he was severely wounded in an assassination attempt, and a few years later, after strokes that left him mute and bedridden, he died.

In the 90 years since his death, more than 10 million people have visited his glass tomb, viewing a body that appears as fresh as the day he died.

To keep Lenin’s body looking normal, artificial eyelashes were added early on to make his face look more natural. To maintain the original look of Lenin’s skin, Yurchak says the Mausoleum Lab applied special dyes and lit him with micro-lamps covered by colored filters. And to replace liquefying fat deposits that normally give shape to the body’s face, limbs and torso, the lab formulated an easily shaped and injectable mixture of paraffin, glycerin and carotene.

Over the years, a myriad of microphotographs of the surface of Lenin’s body have helped the lab keep track of changes that might need correction. It takes ceaseless work to maintain the flexibility of joints and body parts, even those the public cannot see. Yurchak says that every 18 months Lenin’s body is subjected to “big procedures” lasting two months, when it is thoroughly examined, tested and completely re-embalmed.

The same Russian scientists who have preserved Lenin’s body have also used their skills to preserve the bodies of other communist leaders, including Gyorgi Dimitriov of Bulgaria and North Korea’s Kim Jong-il. Yurchak says the work for North Korea was performed to raise money to run the lab after the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991 and government support dried up.

What hasn’t dried up since the death of Soviet communism and the sometimes violent Russian identity crisis that’s followed is the fiery discussion over what to do with Lenin’s body. Yurchak says it is part of an ongoing Russian national conversation that tends to heat up every April around the date of Lenin’s birth.

“Every year around his birthday there is an explosion of debate about Lenin’s body,” says Yurchak. “Shall we cremate it, shall we move the body or the tomb, or just leave it as it is? The unspoken answer of the current government is to leave it as it is.”

Meanwhile, Russian president Vladimir Putin insists that Lenin’s body ought to remain on public view as an irreplaceable symbol of the nation’s history. He suggests that Soviet history deserves as much respect as any other part of Russian history or the history of other countries. In 2000, soon after becoming Russia’s president, Putin resurrected the Soviet national anthem, albeit without mention of Joseph Stalin, whose actions are seemingly irredeemable.

“‘George Washington had slaves, but Americans don’t demonize him for that,’ is how some Russians put it, a view regularly voiced in Russia by pro-government intellectuals and circulated by pro-government media.” says Yurchak. “In the case of Lenin, Putin and others say, ‘It’s too soon to evaluate Lenin’s place in history. Let’s not succumb to foreign comments. Let’s deal with Lenin ourselves.’”