When it comes to communicating with each other, some cells may be more “old school” than was previously thought.

Certain types of stem cells use microscopic, threadlike nanotubes to communicate with neighboring cells, like a landline phone connection, rather than sending a broadcast signal, researchers at University of Michigan Life Sciences Institute and University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center have discovered.

The findings, published online July 1 in Nature, offer new insights on how stem cells retain their identities when they divide to split off a new, specialized cell.

The fruit-fly research also suggests that short-range, cell-to-cell communication may rely on this type of direct connection more than was previously understood, said co-senior author Yukiko Yamashita, a U-M developmental biologist whose lab is located at the Life Sciences Institute.

“There are trillions of cells in the human body, but nowhere near that number of signaling pathways,” she said. “There’s a lot we don’t know about how the right cells get just the right messages to the right recipients at the right time.”

The nanotubes had actually been hiding in plain sight.

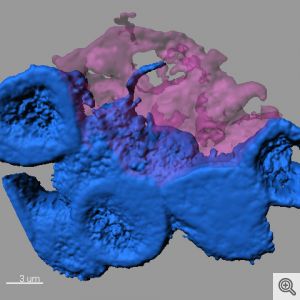

The investigation began when a postdoctoral researcher in Yamashita’s lab, Mayu Inaba, approached her mentor with questions about tiny threads of connection she noticed in an image of fruit fly reproductive stem cells, which are also known as germ line cells. The projections linked individual stem cells back to a central hub in the stem cell “niche.” Niches create a supportive environment for stem cells and help direct their activity.

Yamashita, a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator, MacArthur Fellow and an associate professor at the U-M Medical School, looked through her old image files and discovered that the connections appeared in numerous images.

“I had seen them, but I wasn’t seeing them,” Yamashita said. “They were like a little piece of dust on an otherwise normal picture. After we presented our findings at meetings, other scientists who work with the same cells would say, ‘We see them now, too.'”

It’s not surprising that the minute structures went overlooked for so long. Each one is about 3 micrometers long; by comparison, a piece of paper is 100 micrometers thick.

While the study looked specifically at reproductive cells in male Drosophila fruit flies, there have been indications of similar structures in other contexts, including mammalian cells, Yamashita said.

Fruit flies are an important model for this type of investigation, she added. If one was to start instead with human cells, one might find something, but the system’s greater complexity would make it far more difficult to tease apart the underlying mechanisms.

The findings shed new light on a key attribute of stem cells: their ability to make new specialized cells while still retaining their identity as stem cells.

Germ line stem cells typically divide asymmetrically. In the male fruit fly, when a stem cell divides, one part stays attached to the hub and remains a stem cell. The other part moves away from the hub and begins differentiation into a fly sperm cell.

Until the discovery of the nanotubes, scientists had been puzzled as to how cellular signals guiding identity could act on one of the cells but not the other, said collaborator Michael Buszczak, an associate professor of molecular biology at UT Southwestern, who shares corresponding authorship of the paper and currently co-mentors Inaba with Yamashita.

The researchers conducted experiments that showed disruption of nanotube formation compromised the ability of the germ line stem cells to renew themselves. The work was supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and the MacArthur Foundation.