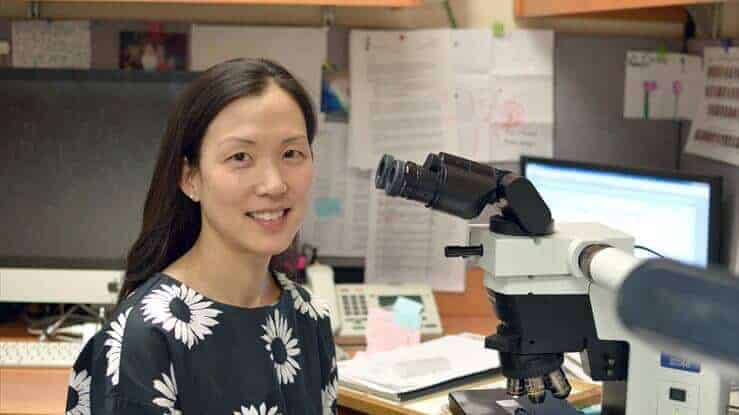

Peering through a microscope, Dr. Christine Ko sees questions.

As a dermatologist, she often struggles to determine if a type of skin cancer commonly found on women’s legs is slow-growing or more aggressive. But even calling on her extensive experience as a dermatopathologist trained to diagnose skin cancers in the laboratory, the answers remain equally hard to reach.

“We rely so much on what we see,” Ko said. “But there are clues inside these damaged cells that we are missing.”

Ko has launched a study to see if a mutated gene can serve as a biological marker to predict the growth rate and recurrence of squamous cell carcinoma, a type of tumor of the thin outer layer of skin that affects about 700,000 Americans each year. More common in women, this cancer often appears on the lower leg and requires doctors to remove the skin, leaving a large hole that can be painful, difficult to heal or replace with a graft, and lead to complications from multiple removals because of recurring cancer.

Funded by Women’s Health Research at Yale with co-funding from the Yale Comprehensive Cancer Center, the study aims to identify which forms of the cancer are slow-growing so that doctors could treat it much more conservatively than a full excision. Because there is no current way of knowing if the cancer might be more aggressive and potentially life threatening, doctors tend to choose the more aggressive treatment to be safe.

“Sitting at the microscope and seeing this uncertainty in the cell’s appearance, we probably over-diagnose rather than under-diagnose,” Ko said. “If we could figure out a better way, it would be truly helpful to our patients.”

Toward that end, the study seeks to find a distinction in the variety of abnormal sequences, or mutations, seen in a cell’s genetic code. Armed with this new knowledge, doctors could determine which mutations drive the growth and spread of the cancer and which act more like harmless bystanders.

What are those bystander mutations doing there if not contributing to the growth and spread of the cancer? Why would a generally aggressive cancer have fewer mutations than a slower growing cancer, as researchers have observed?

“We just don’t understand the contributions of the mutations that we see,” Ko said. “I’m hoping that my research will shed light on this to guide treatment.”

Now that we have more molecular tools available, we can potentially be more precise and save the patient from unnecessary procedures and worry.”

Not only could better information lead to less invasive treatments with better outcomes, but the research could provide relief to patients who have limited ability and often little interest in grappling with medical uncertainty.

“They are shouldering the unknown,” Ko said.

And the new study should help clarify the uncertainty, offering a more precise tool to help pathologists fine-tune their already highly developed and acute visual skills.

“The diagnoses that we currently make are based on visual clues,” Ko said. “Now that we have more molecular tools available, we can potentially be more precise and save the patient from unnecessary procedures and worry.”

Ko has no plans to abandon her clinical practice at Yale-New Haven Hospital and enter research full-time. But her new study helps feed her passion to better understand the diseases that affect her patients, reflecting the same passions that drew her first to dermatology and then dermatopathology.

“I wanted to be an internist, and ended up really liking dermatology,” she said. “You can make a difference that’s visible to patients.” And what appeals to her about studying the diseases under a microscope? “I like detective work,” she said.