Hormones play a two-part role in encouraging and reinforcing cheating and other unethical behavior, according to research from Harvard University and The University of Texas at Austin.

With cheating scandals a persistent threat on college campuses and financial fraud costing businesses more than $3.7 trillion annually, UT Austin and Harvard researchers looked to hormones for more answers, specifically the reproductive hormone testosterone and the stress hormone cortisol.

According to the study, the endocrine system plays a dual role in unethical acts. First, elevated hormone levels predict likelihood of cheating. Then, a change of hormone levels during the act reinforces the behavior.

“Although the science of hormones and behavior dates back to the early 19th century, only recently has research revealed just how powerful and pervasive the influence of the endocrine system is on human behavior,” said the corresponding author and UT Austin professor of psychology Robert Josephs.

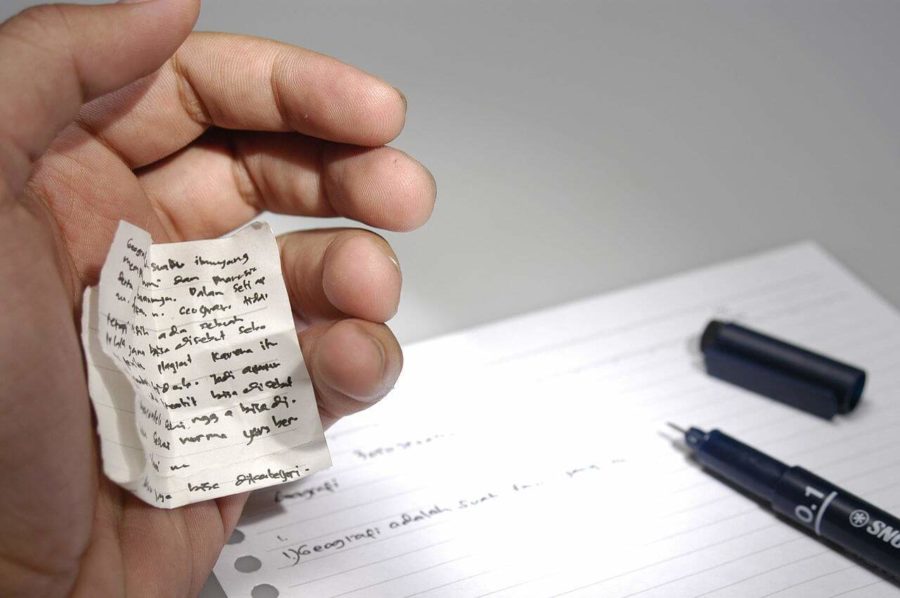

Researchers asked 117 participants to complete a math test, grade it themselves and self-report the number of correctly completed problems. The more problems they got correct, the more money they would earn.

From salivary samples collected before and after the test, researchers found that individuals with elevated levels of testosterone and cortisol were more likely to overstate the number of correctly solved problems.

“Elevated testosterone decreases the fear of punishment while increasing sensitivity to reward. Elevated cortisol is linked to an uncomfortable state of chronic stress that can be extremely debilitating,” Josephs said. “Testosterone furnishes the courage to cheat, and elevated cortisol provides a reason to cheat.”

Additionally, participants who cheated showed lowered levels of cortisol and reported reductions in emotional distress after the test, as if cheating provided some sort of stress relief.

”The stress reduction is accompanied by a powerful stimulation of the reward centers in the brain, so these physiological psychological changes have the unfortunate consequence of reinforcing the unethical behavior,” Josephs said.

Because neither hormone without the other predicted unethical behavior, lowering levels of either hormone may prevent unethical episodes. Prior research shows that tasks that reward groups rather than individuals can eliminate the influence of testosterone on performance; and, many stress relieving techniques such as yoga, meditation and exercise reduce levels of cortisol, Josephs said.

“The take-home message from our studies is that appeals based on ethics and morality — the carrot approach — and those based on threats of punishment — the stick approach — may not be effective in preventing cheating,” Josephs said. “By understanding the underlying causal mechanism of cheating, we might be able to design interventions that are both novel and effective.”

The UT Austin and Harvard study “Hormones and ethics: Understanding the biological basis of unethical conduct” was published in the August 2015 edition of Journal of Experimental Psychology: General.